In September’s Socialist Voice, two articles (“Not seeing the wood for the trees” by Ernst Schreiber and “Unity is strength” by Laura Duggan) raised issue with a piece written by this contributor in the August issue (“The wrong act?”). I will confine my response to the former, because, in contrast to Laura’s piece, Ernst’s article explicitly refers to, and unfortunately misrepresents, my views on several occasions. I will also make some wider points about his alternative.

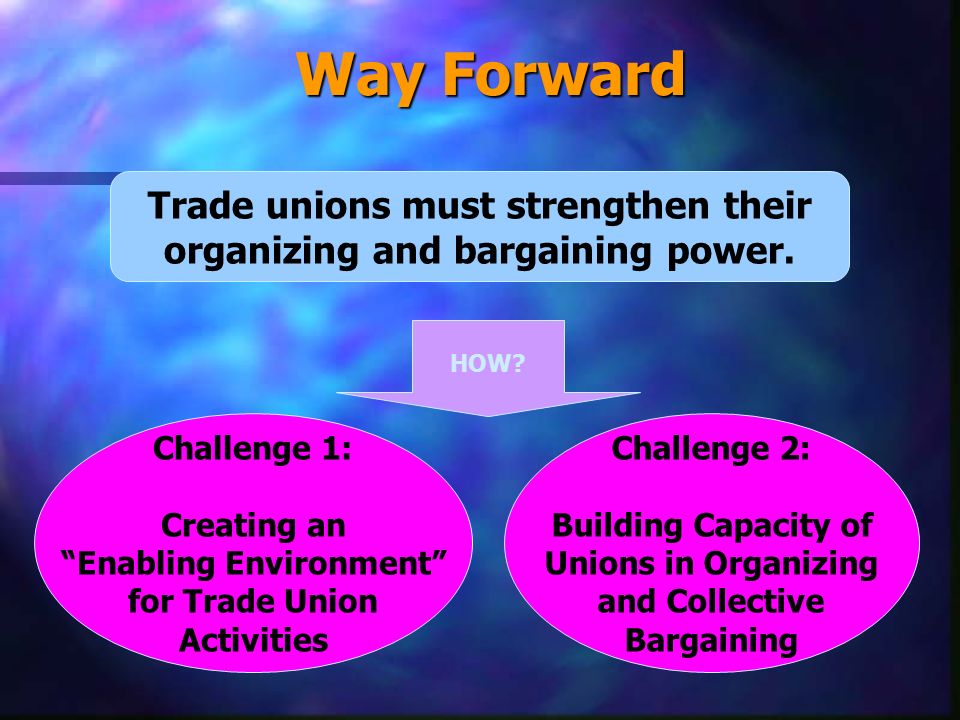

With the greatest of respect to Ernst, “The wrong act?” did not propose the “right to access” as “the focus of rebuilding the trade union movement.” Rather it stated that “the right to organise, the right to access workplaces and the right to recognition for collective bargaining is a more viable platform for the left to campaign upon” in industrial relations terms relative to campaigning on the dismantling of strike law.

Organising, access and recognition are three separate industrial relations issues, with different implications, pros and cons. “The wrong act?” presented them in aggregate to emphasise a measure of a “more viable” industrial relations campaign than strike law repeal, “viable” being understood as likely to draw in a range of progressive actors and institutions on issues of importance and meaning to them.

If you are going to campaign on something, you may as well campaign on the right thing. Whether these will “rebuild” the trade union movement in and of themselves, I suspect not, but they remain a good starting-point and would certainly complement the “building up of workplace organisation and trade union consciousness in the capitalist sector of the economy” that I argued for.

Indeed the writer ignores the fact that organising and not access per se was specified as a priority in “The wrong act?” There is, incidentally, nothing technocratic about arguing for social change based on engaging and organising working people.

The writer engages in another misrepresentation by claiming the alleged consequence of my stance is “to hope for an amenable Government” and to “mortgage our hopes” on Sinn Féin. The article said nothing of the sort. It highlighted that union recognition—a different issue from access, incidentally—is likely to become prominent. Why? Firstly, Sinn Féin declare this as part of their programme for government and have pushed two bills on the matter of representation, and they may well feature in some forthcoming government mix-up. It seems they are courting sections of the labour movement on that basis.

Secondly, there is evidence that the ICTU are now seeking a constitutional amendment or statutory support on recognition rights, because they see little of benefit in the right-to-bargain provisions in the Industrial Relations (Amendment) Act (2015).¹

Now, these are statements of fact and plausible inference about issue prominence, not normative positions of political commitment. We can and should debate the relative weight and significance of these developments: for example, how credible are Sinn Féin on industrial relations issues once in office? But we cannot conclude that a statement of fact signifies support for Sinn Féin, or reliance on government alone (although trade unions rarely develop high density and institutional security in capitalist economies if the state is not sympathetic). The ultimate point was, however, that if an issue relating to organising people at work is gaining prominence among key forces it might be important to have something to say about it.

As such, it is better to speak to people on issues that matter to them using our analysis to show insight and understanding than on issues that only infatuate romantic ideologues of the left.

Although both articles in September’s Voice chose to ignore evidence, strike action is a minor feature of the contemporary class struggle and confined to pitiful numbers of workers. To put it starkly, the total number of workers on strike in Ireland in 2017 was 0.4 of 1 per cent of the working population—a pattern broadly consistent with two decades of data.² Is this what the serious left want to focus on in 2018? Does the repeal of strike laws, or, for that matter, hanging around pickets (and more on that anon), speak to the concerns of the 99.6 per cent of the working population and their day-to-day experience in work and wider social relations?

I appreciate that some comrades want to remain one step ahead of “the masses” and not capitulate to their ignorance. Hence we should, the notion goes, agitate about the importance of strikes. This fails to note that not all strikes are important, or politically significant, from a Marxian point of view, and indeed history shows that outside very particular conditions they are easily accommodated within the normal structures of collective bargaining (of which they are in most cases a simple extension).

Furthermore, in wanting to remain one step ahead of the working population, which is understandable, it should be remembered that we need only be one step and not so far ahead as to be completely out of sight. Having read the alternative presented in “Not seeing the wood . . .” I fear the writer is not only out of sight but full-blown over the cliff and hurtling for the rocks.

So let us consider his alternative. Having misrepresented my argument and mistakenly conflated the right to access with a union servicing model, the writer urges us to “break entirely with the current paradigm” and “systematically dismantle the entire architecture” of Irish industrial relations. He repeatedly refers to this “paradigm” as “social partnership,” even though that very weak form of corporatism has not operated in Ireland for nearly ten years. Most of the ideologies and institutions he associates with social partnership predate it by several decades, and their ideological significance in real terms in any case is over-inflated. Studies on Irish unions and workers show that the presence of workplace partnership was negligible and that management-union attitudes remained at broadly arms-length adversarial engagement.³

Once we look behind the fine-sounding rhetoric, how is this “systematic dismantlement” to happen? A crack troop of “community groups” turning up at a shopping centre pickets for a “direct assault.” In sum, the reduction of industrial relations strategy to picket-line adventurism. Given that Trotskyists have tried this schtick out for decades, one might forgive me for predicting entirely derisory results.

But no doubt there are elements favouring this alternative and, like latter-day Narodniks, are probably practising it on the unfortunates of Lloyd’s Pharmacy—hence, I suspect, the “shopping centre” reference. When that dispute ends in negotiated compromise, as it inevitably will, the “assault” might well be tried out on another group of unfortunates among the 0.4 of the 1 per cent. The workers of Lloyd’s will fade into memory, as the Greyhound Waste workers did when the juvenile left grew tired of them too. The next worthy victims will be found, and the fetishism of episodic economistic strike action will continue.

I suspect that none of this is based on any hard-headed logic but mere romanticised idealism.

While all this carries on, the IFSC, unorganised transnationals and indigenous employers will accumulate and dictate workers’ pay, pensions, hours and content of labour and directly and indirectly shape many other facets of our society. And they will continue to do this, safe in the knowledge that important radical potential in this society obsesses with the momentary pickets of a transient minority and cannot work out a credible strategy to organise and appeal to the heterogeneous mass of working people.

- “Congress set to pursue union recognition, King sets out options,” Industrial Relations News, June 2018.

- Central Statistics Office, “Statistical product: Industrial disputes,” at www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Database/eirestat/Industrial%20Disputes/Industrial%20Disputes_statbank.asp?SP=Industrial%20Disputes&Planguage=0.

- Daryl D’Art and Thomas Turner, “An attitudinal revolution in Irish industrial relations: The end of ‘them and us’?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 37(1), 1999, p. 101–116.