It was said of the Bourbons after the Restoration in 1814 that they had forgotten nothing and learnt nothing. Something similar may well be said about the DUP in particular and unionism in general.

Having seen its regional parliament collapse yet again in early 2017, and largely as a result of their own ineptitude, they have now contrived to prevent its reconvening any time soon. By focusing on an Irish Language Act, Sinn Féin had asked for a gesture rather than a compromise. Suffering from what can only be described as acute political myopia, unionism brushed aside a reasonable offer and ensured that Stormont would remain in suspension.

According to the usually well-informed Denis Bradley, writing recently in the Irish Times, Sinn Féin had agreed that Arlene Foster would remain as first minister, that there would be no agreement to liberalise legislation on civil marriage or abortion, and that the petition of concern would remain virtually unchanged.¹

Going by this as yet unchallenged assessment, it would appear that the DUP was emerging practically unscathed from the Renewable Heat Initiative scandal. After all, RHI was a costly fiasco of the DUP’s own making, about which even Eileen Paisley said that Foster should have stood aside.

Having secured what promised to be a favourable outcome under difficult circumstance, it was obvious that some reasonable ground would have had to be conceded across the table—in this case a modest demand in relation to cultural recognition. Without the minimal concession of an Irish Language Act, Mary Lou McDonald and Michelle O’Neill would have left the negotiations empty-handed and unable to sell the deal to their rank and file. Unionist negotiators undoubtedly were aware of this yet chose to collapse the talks rather than risk alienating reactionary sections of their electorate.

The dilemma for unionism, however, is not so much that its political leadership is incompetent but that, as a whole, unionism is so determined not to give an inch. As a consequence, it cannot deliver on a programme that would amount to an act of enlightened self-interest.

This position is not tenable in the long run. With a large and growing minority that is, at best, indifferent to the very existence of the six-county state, intransigence is no longer a viable policy. Common sense would dictate that this estranged section of the population needs persuading if it is to tolerate the status quo into the future. As the News Letter’s political correspondent, Sam McBride, wrote a short time back, “the loss of Unionism’s Stormont majority and the growing Catholic population meant that for the Union to survive they [unionists] will have to make Northern Ireland a comfortable place for cultural nationalists . . .”²

However, history and longing for a past that never was as rosy in reality as in nostalgia-coloured musings prevent many unionists from recognising this reality. In the absence of that all-important consensus about its governance, Northern Ireland remains a failed and decaying political entity.

In spite of this, efforts are being made to convince the Northern public that the Stormont Assembly might have some meaningful authority if the institutions were up and running. Hardly an evening goes by without one of the Belfast broadcasters carrying a story about how the absence of a local administration is hindering efforts to activate and deliver on some much-needed public service.

South of the border the scene is little different, as Government ministers speak anxiously about the need to restore devolved institutions—some even going so far as to claim that this would allow the North to have a say in the Brexit deliberations, conveniently overlooking the fact that London has given no consideration whatsoever to the North’s Remain vote during the referendum.

In reality, the North’s Assembly has very limited power, as it is deprived of fiscal authority by central government in London. Stormont is awarded an annual block grant by the British exchequer and cannot deviate from this amount. Even when it is sitting, ministers in the Executive are usually directed by their senior civil servants on how and where to allocate funds.

Moreover, if we are to believe the testimony of various witnesses at the RHI inquiry, ministers, including the aforementioned Arlene Foster, are not always aware of the details of their department’s expenditure.³ In other words, it is difficult to know exactly what impact having devolved institutions has, as Britain sets the budget and senior civil servants in effect determine its allocation.

The Stormont assembly, nevertheless, does have some capabilities that, if utilised, would make a difference for working people. One such “devolved power” available to the local administration is control over industrial relations legislation. This would mean, for example, that in the Six Counties zero-hour contracts could be outlawed, an end put to the scam whereby employees are illegally designated as self-employed, and the introduction of a realistic minimum wage.

Disappointingly, Sinn Féin did not focus on areas such as these and instead chose to make the introduction of an Irish Language Act a cornerstone of their negotiation. Let us be clear, though, that this is not a criticism of the party’s position on the language. There is an unanswerable case to be made for such legislation, and only ignorance, coupled with opportunism, prevented it happening. Nevertheless, in the light of the failed and failing nature of the Northern state and its uncertain future, it would surely be prudent to adopt a strategy highlighting a progressive republican agenda.

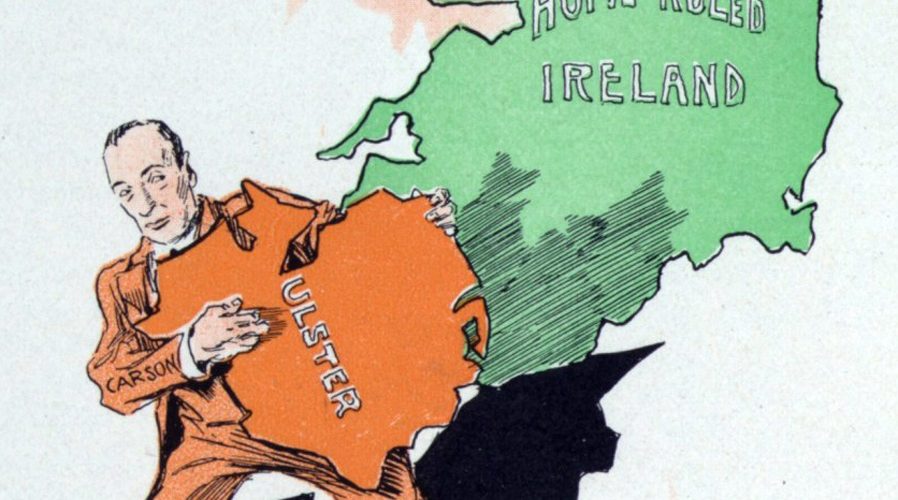

Unionism has traditionally sought to argue that any dilution of the link with Britain would lead to the creation of an intolerable climate for its supporters on this island. A century ago it was a claim that home rule would mean Rome rule; now it is an assertion that Ulster unionists would be culturally swamped and thus disfranchised. No matter how unfounded these claims may be, reactionary scaremongers find them convenient, because by their nature they are vague, ill-defined, and therefore difficult to refute.

On the other hand, a package demanding sufficient fiscal authority to implement a public housing programme, an improved local NHS, an end to the privatisation of essential services and meaningful rights for workers would have forced unionist naysayers onto different ground. This might not have led to a restored Stormont Assembly; it would, though, have outlined a progressive path for the future and left the DUP Bourbons trying to remember why exactly they wish to hold on to a failed state.

- Denis Bradley, “How do you solve a problem like unionism? Unionism’s usual ‘no’ response will not serve it well in coming to terms with what lies ahead,” Irish Times, 21 February 2018.

- Sam McBride, “Shambolic DUP talks tactics dismay key figures—and weaken the leader,” News Letter, 24 February 2018.

- Conor Macauley, “RHI Inquiry: Foster not told of hike in RHI costs,” BBC Northern Ireland, 7 December 2017.