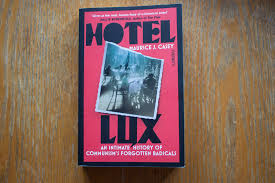

Hotel Lux: An Intimate History of Communism’s Forgotten, by Maurice J Casey – review

Richard Mullen

The blurb on the back cover of Hotel Lux reads: “A series of romances wrapped in a detective story, disguised as a narrative history of international communism, Hotel Lux uncovers a world of forgotten radicals who saw their hopes and dreams crash against reality, yet retained their faith in a beautiful future for all.” It is rather accurate: for the reader interested in the romance-laced detective story, the author, Maurice J Casey, has them covered. For the reader interested in the narrative history of international communism, they may have been tricked by the disguise.

Hotel Lux is a book about a loose network of people connected by the space of Hotel Lux and the place in the 1920s Soviet Union and the Comintern. Starting from the story of May O’Callaghan in the Translation Section of the Comintern, Casey explores the lives of people connected to O’Callaghan: more and less famous faces of the first half of the 20th century Ireland, England, continental Europe, and the Soviet Union. Reconstructing the relationships through correspondence and other primary sources, Casey tells an interesting personal story of O’Callaghan and the circle around her—especially the women.

Some writing choices do raise the question of the intended audience for this book. Early on in the book, in the first two references to the “Stalinist Terror” he makes (p. 10, p. 76), Casey puts them in the same sentence as the Holocaust. This particular choice has been used throughout the Cold War and beyond by the Western authors to cement the otherwise untenable position of Hitler and Stalin being somehow comparable. Domenico Losurdo has written extensively on this juxtaposition of Nazis and Soviets as a form of blatant revisionism: while I do not think Casey’s motives were revisionist, it is indicative that this phrasing was left in place. Another particularly puzzling phrase Casey uses appears on page 77, where, after hearing a Russian person in Moscow disagree with Putin’s politics, he writes “… this made me feel as though I was in just another normal European society.” Again, I give Casey the benefit of the doubt, but find it indicative once again that the editor thought this was an appropriate line. In a similar vein, I found it a strange decision to call factional disagreements in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union “tribalism”.

Still, my biggest issue with the book stems, probably, from the “history of international communism” disguise. There might be readers who, after finishing this book, find that they know everything about the protagonists. I, for one, do not know anything about the politics of anyone in the book. I know that Liam O’Flaherty occupied the Rotunda and that May O’Callaghan was suspected to be a Trotskyist, but I still do not know why. While I do suspect that for some of the people whose lives Casey was reconstructing, extensive political writings would not exist, Casey does reference Emmy Leonhard’s detailed political letter to Trotsky. Knowing more about actual political beliefs and organisational interactions of these people, superimposed onto the material conditions and the context would help move the narrative of the book beyond “radicals who saw their hopes and dreams crash against reality, yet retained their faith in a beautiful future for all”. The references to utopian visions, abstract hopes, and idealism appear more often than one would expect; they seem far removed from what the Marxist perspective would have been and again maybe catering to an audience without a materialist outlook.

Maurice Casey’s Hotel Lux nevertheless remains an interesting read; Casey has both the skills of a historian and the style of a good author.

Hotel Lux: An Intimate History of Communism’s Forgotten (Maurice J. Casey, Footnote Press, 2024) is available from Connolly Books, Temple Bar, Dublin. https://www.connollybooks.org/product/hotel-lux-an-intimate-history-of-communisms-forgotten-radicals