James Baldwin was born one hundred years ago in Harlem, New York, 2 August 1924. Baldwin’s stepfather David, a Pentecostal preacher, was a factory worker, earning too little to provide for his family of nine children. His mother Berdis, a migrant from the South, worked in domestic service. The young James’ first encounter with police at the age of ten brought home to him the realities of racism.

During his time at Public School 124 in Harlem (with its first Black principal, Gertrude Ayers), Baldwin’s potential was recognised by Orilla Miller, a white teacher and communist from the Midwest. Miller introduced him to literature and theatre. Through the Millers, Baldwin learned that racism could be opposed and solidarity could be built across racial lines. These experiences, as well as the Harlem Renaissance, deepened Baldwin’s literary passion and provided a secular alternative to his religious upbringing.

Baldwin’s political consciousness was further shaped by his communist English teacher Abel Meeropol, author of the anti-lynching song “Strange Fruit”. Meeropol also adopted of the sons of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. His encounter with Beauford Delaney introduced Baldwin to the secular tradition in Black music, which transformed his emotional experiences into artistic expression.

Leaving school in 1942, he was unable to afford college. He joined a writers’ workshop taught by communist Mary Elting. The 1943 Harlem riots and Baldwin’s experiences further fuelled his radicalisation. He joined the YPSL, navigated various left-wing camps and published poetry in the CPUSA’s Daily Worker. Between 1920 and 1950, many Black intellectuals, including Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, and Richard Wright, found a political and artistic home here, though some drifted away from it again.

These formative experiences solidified Baldwin’s commitment to social justice and influenced his decision to move to Paris in November 1948. Here he found the freedom to explore his identity, including his queerness, and to articulate his revolutionary ideas. Baldwin’s debut novel, Go Tell It On the Mountain, draws on his upbringing in Harlem, became part of African-American protest literature, articulating the realities of oppression. Baldwin’s writing career encompassed bestselling novels, essays, plays, and articles. His major political works, such as The Fire Next Time (1963) and No Name in the Street (1972), were penned abroad, addressing international issues.

In Paris, he became aware of the struggles of North African refugees, seeing global struggles as interconnected. Baldwin’s awareness of Black internationalism addressed Western imperial power in the Middle East. He was a vocal supporter of Palestinian self-determination, viewing Israel as a proxy for Western imperialism and Palestinians as oppressed victims. His experiences with the civil rights movement and French colonialism’s brutality, especially during the Algerian war, reinforced his understanding of international racism and state terror. This period included significant travel, writing, and a deepened interest in Islam and anti-colonial struggles.

Baldwin’s visit to Israel shifted him further away from a Western perspective towards anti-imperialist internationalism, perceiving this country as a pawn in the Middle East, created to serve Western imperialist interests. International events like the Vietnam War and Israel’s Six-Day War aligned Baldwin with SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and the Black Panthers, seeing these conflicts as expressions of US imperialism and racism.

By 1968, Baldwin had become closely affiliated with the Black Panther Party. He endorsed their community programmes and their stance against police violence, viewing them as a challenge to the repressive US state.

No Name in the Street articulates Baldwin’s anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist stance, opposing the Vietnam War, South African apartheid, and Israeli settler-colonialism. It expressed solidarity with liberation movements and predicted a socialist future. His relationship with Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party underscored his commitment to long-term anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggle.

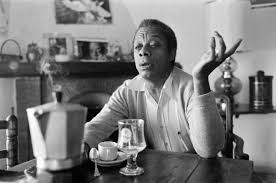

Between 1968 and 1972, Baldwin spent much of his time outside the United States, initially in Turkey and France after traumatic events like the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.. During this period, he ended his relationship with his lover Alain and, coupled with the 1971 Turkish military coup and his declining health, decided to permanently move to St. Paul-de-Vence in France, buying a home there.

In October 1973, following US support for Israel during the “October War” against Egypt and Syria, Baldwin made his strongest public criticism of Zionism and expressed support for Palestinian rights. He highlighted the creation of Israel as a means to control Arabs, condemning the Western powers for using Israel and Vietnam to enforce their interests.

The Reagan administration, with its harsh stance on issues like HIV/AIDS, intensified Baldwin’s despair and rage over the United States. Baldwin received an honorary doctorate from the University of Massachusetts in 1978 and became a Distinguished Fellow there in 1983. He continued his work as a political journalist and author, producing his only poetry book and his final novel, Just Above My Head.

In his 1979 essay, “Open Letter to the Born Again”, Baldwin condemned Western anti-Semitism and expressed solidarity with Palestinian self-determination, criticising the Zionist project and its colonial roots.

Towards the end of his life, Baldwin sought to redefine gender and racial identities. Diagnosed with oesophageal cancer in early 1987, Baldwin spent his remaining lifetime at his home in St. Paul-de-Vence, passing away aged 63 on December 1, 1987.