The painter of Renaissance humanism

Hans Holbein the Younger, born in Augsburg in the winter of 1497/98, was one of the foremost German painters of Renaissance humanism.

Augsburg was the seat of the Fugger family, trading magnates and bankers. Jakob Fugger “the Rich,” elevated to the nobility of the Holy Roman Empire in 1511, is still considered one of the richest people who ever lived.

In 1514/15 Holbein settled in Basel. In 1516, during this period of revolutionary change in book design, Holbein produced marginal drawings for Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly, a sharp critique of scholasticism. In the same year Thomas More’s seminal work Utopia was published, which Holbein also illustrated.

In 1517 Luther initiated the Reformation. In 1519 Holbein married Elsbeth Binsenstock, enabling him to become a citizen of Basel and a member of the city’s painters’ guild.

In the early 1520s Ulrich Zwingli initiated the Reformation in Switzerland. In 1524 Holbein began working on the Dance of Death images and fundamentally redesigned an old theme in forty variations. During this time the Peasant War broke out in Germany. Luther betrayed the peasants, who were devastatingly defeated by the princes at Frankenhausen.

In 1526, through the mediation of Erasmus, Holbein travelled to England and spent nearly two years in the home of Thomas More and his humanist circle. His portraits of English personalities included More himself and the Archbishop of Canterbury.

At this time Dürer sided with the revolutionary peasants and embraced the Reformation. Paracelsus burned books of scholastic medicine at the University of Basel and proclaimed his new curriculum.

In 1528 Holbein returned to Basel, where many old patricians fled the city, and churches were left to the Protestants, accompanied by a fierce wave of iconoclasm. As one of the first representations of an artist’s own household, Holbein painted The Artist’s Family (1528). In 1529 Erasmus left Basel, and in 1532 Holbein settled in London, where in 1536 he became the court painter of King Henry VIII.

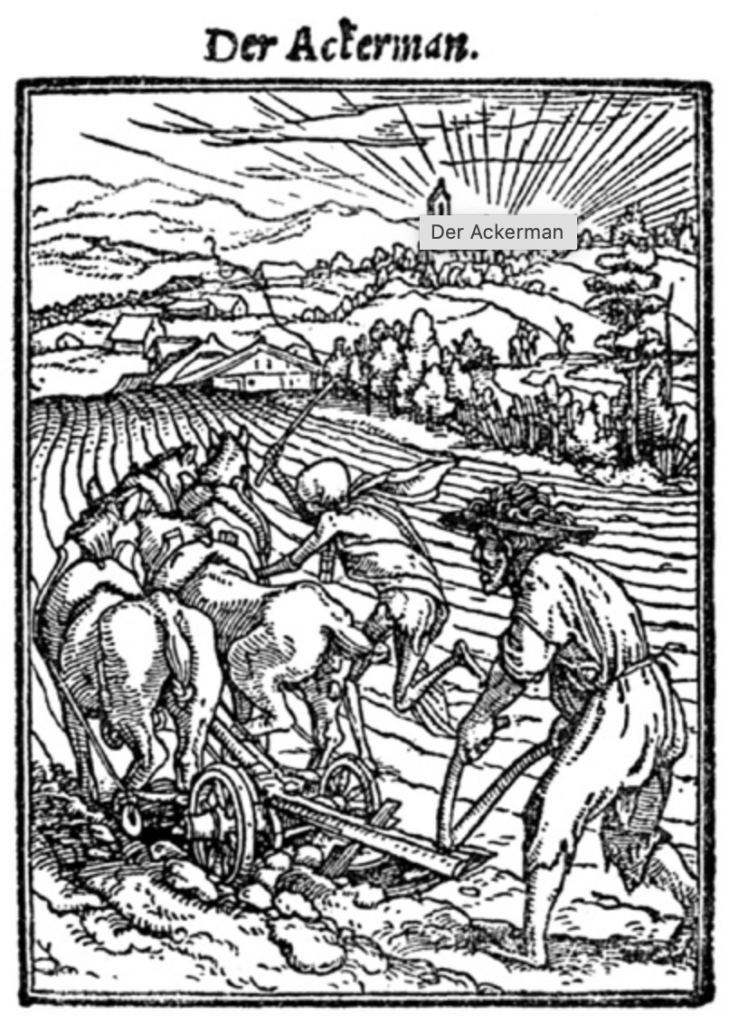

Holbein’s early work shows a strong anti-Roman tendency. Similar to other humanists in Basel, he desired church reform but hesitated to fully break with the traditional faith, fearing that the Reformation might promote popular opposition. However, until the Peasant War, Holbein can be seen as supportive of the reformist movement. He created woodcuts that denounced the papacy and the sale of indulgences and depicted fighting peasants. Most notably, his cycle The Dance of Death, created during the Peasant War, contains profoundly anti-clerical and democratic statements. The Dance of Death genre had been passed down since the fourteenth century, but Holbein infused his depictions with the spirit of the Reformation.

It is striking how many clergy and secular authorities are claimed by Death here. They are typically portrayed as well-fed and indifferent to the suffering of the people. The impoverished common people are visited by Death while working. The Duke is captured by Death at the moment he rejects a starving woman with her child; the Senator pays no attention to the beggar; the devil of pride sits on his shoulder. The Judge is bribed by the rich, while a poor man stands helplessly at the edge of the image. The judge’s staff is in the hand of Death.

The Lawyer too is bribed by a wealthy citizen, while the poor man watches powerlessly with his hat in hand. The Rich Man, with the features of Jakob Fugger, sits over his treasures in the cellar with heavily barred windows, where Death finds him.

On another sheet the Merchant’s splendid trading ships lie in the harbour, their flags flying in the wind, favouring trade. Goods from all over the world are unloaded, securely packed, soon to be turned into profit. But here too Death pulls at the merchant’s coat while he vainly clings to the packaging ropes.

Death takes the Nun in her cell in front of the altar as she turns to her lover, seated on her bed. In the image The Young Child, a woman with children in a miserable hut prepares soup over an open fire; Death takes her youngest. The Ploughman, barefoot and ragged behind the plough, is too weak to dig deep furrows. Death drives the horses, and the peasant works until his end. For him, a peaceful, sunny landscape with a village on the horizon suggests Paradise, perhaps joined with Thomas More’s earthly Utopia, the island without a place for the wealthy, where private property is abolished.

In his final years in London, Holbein, as a court painter, became a celebrated artist who portrayed the rich and powerful, designed decorations for court festivities, and created jewellery, plates, and other valuable objects. His paintings of the royal family and the nobility testify to the royal court during the time when King Henry solidified his control over the Church of England, separating it from the Roman Church and the papacy. Holbein increasingly distanced himself from his humanist positions, to the great disappointment of Erasmus.

The political and religious climate in England had drastically changed. In 1532 King Henry challenged the authority of the Pope when he annulled his marriage to Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn. More opposed this move and in May 1532 resigned from his office as Lord Chancellor (supreme judge and adviser to the monarch). In 1535 More was beheaded. To Erasmus’s great disappointment, Holbein distanced himself from More’s humanist circles and found patrons among the new power circles.

Holbein died 480 years ago, in October or November 1543, at the age of forty-five.