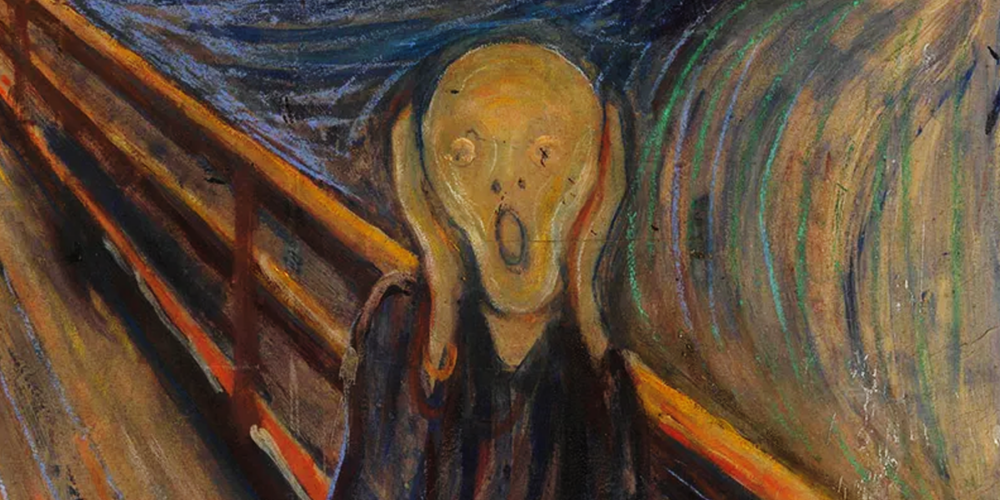

Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) speaks to us again today with great intensity. Why has this painting become so indelibly engraved in the collective memory of the human community?

The figure not only hears the scream, he is also screaming in despair. His hands cover the ears to protect them from the scream, but also manifest his own horror. This scream is profoundly elemental.

A vivid description in Munch’s diary already contains aspects of the painting. There are references to flames, fire, even the fjord and the mountains are bathed in “the exploding bloody red”. The sky exudes blood, fire and violence, takes up a third of the picture and radiates onto the dark mountains and the fjord, which is framed by the mountains and the town of Kristiana (Oslo) in reddish brown and blue tones. The city itself is only hinted at.

The curved brushstrokes in oil and tempera as well as highlights in pastel chalk, applied directly to the brown, unprimed cardboard, capture the movement and sound waves of the scream. These sound waves are emphasised by the shrill contrasts of glaring yellow with crimson and dark. This clash of bright with broken colours infuses nature with a simultaneously horrific and ominous, impenetrable character.

The painful nature of the scream is emphasised by colliding forms: Vibrations, curves and abysses dominate two thirds of the picture; one third is filled by the dead straight lines of the bridge and the horizontal struts of the railing. The picture is thus divided into two large, contrasting triangles: one belongs to the outcry of nature, which still also harbours people with its soft, flowing lines. The smaller triangle to the left of the bridge railing is characterised by taut, hard diagonals that run through the picture like an arrow. A funnel shape of dark blue, within nature, whose tip runs towards the head of the screaming character, creates the sense of inescapable suction, like a black hole, of which only the horror-struck person is aware. The barrier between the bridge and the abyss is quite open and offers no fall protection.

The skeletal head is in the centre of the picture. Munch barely uses any colour to create this face, leaving a large part of it simply on the unpainted brown ground. The mouth, wide open in horror, dominates the face, the nose and eyes are only indicated, white pastel chalk strokes trace the contours of the skull, the eye sockets, the jaws, and deepen the impression of a skeleton; the hands are also reminiscent of bones.

The rest of the body is sketchy – the figure’s jacket reflects the colours of the devouring funnel and becomes shapeless, disembodied from the chest down. The skull seems a little too large for the body, almost too heavy. While the head protrudes into the dark triangle above the railing, the body is located under the bridge railing with its straight lines into the upper third of the left edge of the picture. The railing thus connects the figure in the foreground directly with the two dark, walking figures a short distance away. Top hats point to two conventionally dressed, faceless men. These two men, towards whom the diagonal is pointing, are thus given an impulse to help the martyred person and are thereby included in the action. They, however, do not hear the scream – neither the despair of nature nor the shriek of their fellow human being.

Another doubling, contrasting with the screaming individual, are the two boats seen on the fjord: seemingly enjoying a peaceful evening. Nature is not deserted, but includes human activity. Only the person screaming in deepest distress senses the impending apocalypse. Horror reigns beneath the surface of a peaceful world. Familiar signs can no longer be relied on: red, the colour of love and warmth, now transports fire and blood. The horror to which he sensitises the eyes and ears of the viewer with this picture reflects the fears of the individual and at the same time captures the madness of an era that was heading for the abyss.

The Scream was created in the late nineteenth century, when imperialism emerged as a new, more international, more aggressive stage of capitalism. The world was being redivided, with rapidly growing technological progress and simultaneously increasing urban impoverishment, the First World War cast its shadow long before. Everything seemed to be spiralling out of control. Nihilism, which also affected Munch, gained new fertile ground with its anti-humanist idea of the meaninglessness of life. It suited the ruling class of the era that the world no longer seemed comprehensible.

While the subject matter of the painting depicts a person standing on a bridge near Oslo and hearing a deafening scream (and shrieking himself), the times contribute decisively to its significance. The scream penetrates deep into the composition, into its colours and elements, and is radiated by it, heightening it and moving it towards horror and despair. In the form of his painting, Munch breaks away from Impressionism and describes a world torn apart. Art enters the age of imperialism.

Since its creation 130 years ago, Munch’s picture, like the Mona Lisa or Guernica, has been engraved in the visual memory of humankind. Naturally, personal sensibilities inform a work of art, but its paramount importance lies in the fact that Munch – by facing his own fears, his own pain – was able to express this scream of the tortured creature as a defining moment of the age in such a way that people all over the world are still moved today. Munch’s painting vividly evokes in us an empathy that defines our humanity, which we feel when we hear about natural disasters and other tragedies, but above all about the immense suffering and terror of martyred people in war zones. The Scream expresses deep emotionality and humanity that define its greatness.

I would like to thank Friederike Riese and Erwin Ritzer for their valuable advice.