No historical Irish political figure sums up the politics of the Irish establishment today as much as John Redmond. The class and political interests Redmond embodied during his life have strengthened over recent decades and now appear to dominate most elements of the state, media, and political parties.

Politics is sometimes presented still in simplistic “Civil War divides”: Collins versus De Valera, who fought over abstract symbols and oaths where class and empire didn’t feature.

John Redmond had a clear vision for Ireland, one that placed us as a junior partner in Western imperialism, where, rather than being robbed, we could in fact turn robber and become a recipient of the spoils of empire. In this he vehemently opposed a nationalism that differentiated itself from empire as realised then by the alliance of different forces leading up to the 1916 Rising. Indeed Redmond supported the crushing of the Rising:

This outbreak, happily, seems to be over. It has been dealt with with firmness, which was not only right but it was the duty of the Government to so deal with it.

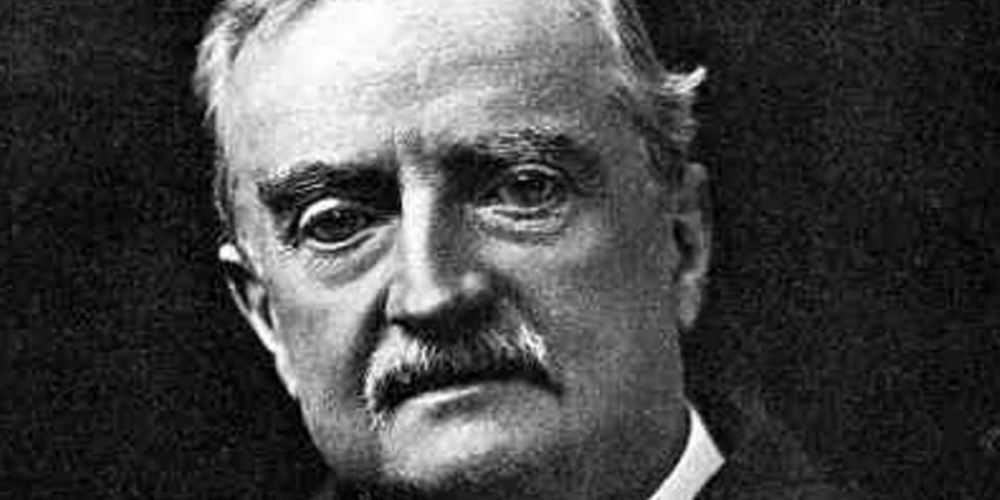

Redmond was born in 1856 and died in 1918 as the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. He led that party from 1900 and was MP for Wexford and Waterford at different points. His family had a wealthy mixed nationalist and unionist background, and in his early political career he sided with the Parnellite faction within the Irish Party.

Redmond is most known for two things: negotiating and supporting the Government of Ireland Act (sometimes called the Home Rule Act), passed in 1914, which provided for an elected assembly in Ireland but subordinate to the British Parliament on all matters concerning finance, trade, foreign affairs, and defence, and, related to this, supporting Britain in the First World War and encouraging Irish volunteers to fight and die in the trenches of Europe. Significantly more Irish men died fighting for British imperialism in that war than died in the Rising.

Redmond’s political vision was to place Ireland within British imperialism so that the “nation” might benefit from it:

As a Nationalist, I do not regard as entirely palatable the idea that for ever and a day Ireland’s voice should be excluded from the councils of an empire which the genius and valour of her sons have done so much to build up and of which she is to remain.

Let us Irishmen of all politics and all creeds put aside these differences which have been dividing us in the past and unite to perform a common duty which we owe to our common country, namely of defending Ireland as an autonomous nation within the Empire . . . and to recognise that we, like them, are at least an autonomous portion of this empire, and that this empire belongs to us, as it does to them.

Redmond hoped that fighting with unionists for the defence of the empire in the First World War might provide the basis for unity and support for home rule from within the unionist population:

One blessed result may come to Ireland, and that is that the blood shed side by side, in the field of battle by Catholics and Protestants, by north of Ireland Irishmen and south of Ireland may prove to be the seed of the future unity of our Irish nation.

Today the politics of Redmond dominates. The establishment has no ambition for economic independence and has firmly linked Ireland’s fortunes to those of global capital. The state has in effect outsourced economic control to the EU and chosen foreign direct investment as its development path, with all the distorting effects this has on internal economic balance.

The political logic behind this is in essence the same as Redmond’s: Ireland should have its slice of empire, and therefore what is good for empire is good for Ireland. Redmond sought

that brighter day when the grant of full self-government would reveal to Britain the open secret of making Ireland her friend and helpmate, the brightest jewel in her crown of Empire.

The recent media and political-led assault on neutrality also relates that economic position to our foreign policy. If the state is now an active participant in global imperialism, and its economic model is to benefit from it, how tenable is neutrality? How tenable is any remnant of independent foreign policy?

These ideas are absolutely related, just as Redmond understood: home rule in return for fighting in the war. Today the quid pro quo of US and EU economic control is falling behind their global imperial strategies. It’s no wonder that John Bruton, when Taoiseach, had a portrait of Redmond hung in his office, Bruton being one of the more open and honest advocates of Ireland being a part of a militarised Western imperialism.

So, rather than viewing Ireland through a lens of Collins versus de Valera, we would be far better understanding Ireland today by reference back to John Redmond. Far from being a “failed state,” Ireland is nearly the perfect embodiment of Redmond’s politics in state form. If partition ends with Ireland remaining a small partner to US, British and EU imperialism, then Redmond’s vision will be complete.

There was, and is, an alternative vision and aspiration for Ireland, and again it was not Collins or de Valera: it was the Ireland fought for by James Connolly and his allies, one that placed economic, political and military independence at the core vision for an Ireland welcoming to others and with people’s collective as well as individual rights at its core. This is a view that needs to be inserted into the debate on our future united Ireland.