Following my previous article on ChatGPT and machine learning models, I would like to shed some further light on why those models should be heavily scrutinised and monitored. So I’m going to share with you a personal story to demonstrate how they can end up being used to expropriate free labour from the working class.

You see, I do photography artwork, and a long time ago I was deceived into believing the dream that I could actually make a living selling photography artwork on line. So I earnestly uploaded my best photos and rigorously tagged and labelled each one with all possible tedious details I could muster to make them “searchable,” as the on-line web sites I uploaded them to claimed back in the time. Eventually I got nothing out of it and forgot all about it.

Recently, after realising after more than a decade and a half of photography that I’ve never made a penny out of it—and if anyone did make a profit on my photos it was the very same web sites that promised me a fortune but never delivered on their promises, which I’m going to explain how—I’ve decided to release those photos freely under creative commons licensing, hoping that someone may benefit from my work rather than seeing it going to waste.

Before committing myself to do it I went on spontaneously revising my old photography portfolio on one of the websites to see if I did in fact sell any photos before releasing them, out of the worry that I might violate any agreement I could have unwittingly signed up to. And, lo and behold, for the first time in my photography career, It turns out that I had in fact achieved a positive income from my investment: the lordly sum of 6 cents!

I was intrigued, apart from the very low unanticipated royalties, to find out which photo did sell for this sum. So I investigated it, only to find that the sale was done under the peculiar new product name “dataset.” After further investigation, it turns out that they didn’t just sell one photo: they sold the whole lot—for 6 cents!—along with all the work I put in to sorting and labelling the photos. Surely if I had put the same amount of effort into working at Subway I would have made much better returns.

It didn’t mention who bought my data, or what they are going to use it for. But it was implied that they are going to be used for computer vision training, a common machine learning model. And it’s of the utmost importance that datasets fed into those models be properly labelled and categorised.

For example, if you use a dataset of photos of dogs and cats to train a computer vision machine learning model to be able to distinguish between them and classify them into their proper classification (hence the term classification algorithms), it has to be tediously labelled. And mind you, it’s not just to say it’s a cat or a dog: the data labelling would go to the extent of describing the photo: lighting, background, items in the photo, and even metadata, such as camera model, lens, and settings, which they sometimes hire workers on full-time jobs just to do. And guess which datasets were labelled in such a manner as to become “searchable”?

That said, I won’t be surprised to see my photos, along with many other artists’ work, floating around the internet free of royalties, with the claim that they have been generated by one of those, by now ubiquitous, stable diffusion models which are known to, conveniently, fail their training and simply spit out the training data back to its users, with very little modifications, if any at all! And good luck trying to build a case against the operators of those machine learning models they are using to infringe your copyright in such an obfuscated manner.

Actually, I was lucky that the web site told me that they sold my artwork for a measly 6 cents. In many cases, those web sites would consider the outcome of “processing” your data as their rightful proprietary data, according to a loophole in GDPR provisions, which basically states that if the data processor does some “processing” on the data to extract some “statistics,” for example, then the outcome of this processing is no longer yours and it’s rightfully theirs. Here’s the thing: machine learning models are nothing but statistical brute-forcing energy-hungry processes!

And, as you can imagine, this phenomenon is not limited to photography artwork. It’s prevalent in many other fields, including—but not limited to—writing, programming, music, videography, content creation, and the entertainment industry in general. It’s no wonder that writers and actors are striking in the face of this absurdity.

Whenever you hear that someone made it and became a millionaire on Youtube, Tiktok, Facebook, Spotify, or whatever on-line entertainment service expects artists to upload their work freely to, don’t believe it! It’s a marketing tactic similar to what they do with the lottery; but at least the lottery people are regulated.

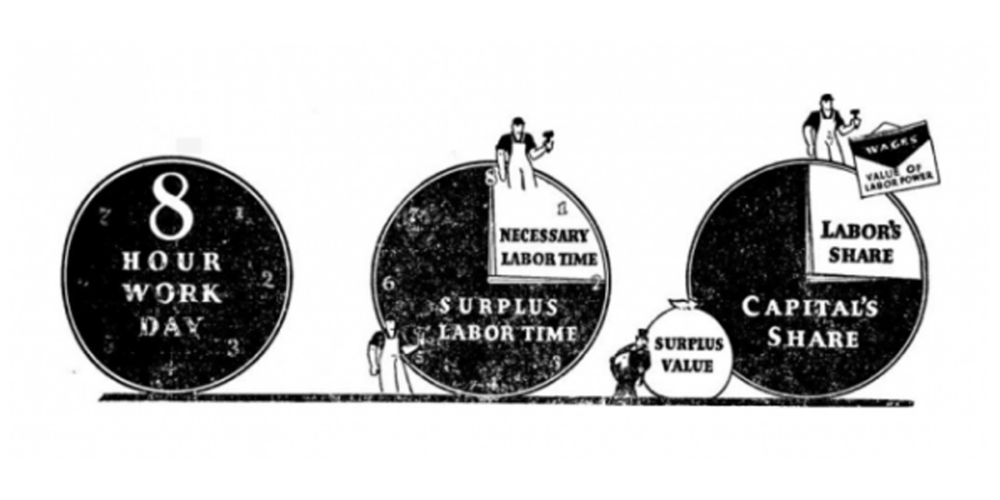

It’s well known, not to mention that I’ve confirmed it for a fact from internal sources, that those contributors make peanuts, if anything at all, out of their labour, no matter how many million views their work may get. While those on-line services would extract massive surplus value out of their free labour if not from the views and entailed advertisement, it would be from selling the data, or using it to train machine learning models, which can be rented for a fee.

And by doing just this they force artists into a lose-lose game, where they are deprived of their livelihood, similar to the prisoner dilemma: either upload your work freely to the likes of Youtube and Tiktok and maybe, maybe, you would win the views lottery and get paid some peanuts or else get lost in oblivion, as, thanks to other free-content uploaders, content creators’ work will never see the sun, as viewers will always have an infinite supply of free entertainment to watch on their web sites and apps. So good luck trying to compete with that.

It’s no coincidence that there is the current dwindling state of affairs in the world of arts, given that now artists have to strain their creative work through formulaic processes designed with the bottom line in mind. Hence the ironic predicament of the entertainment industry, where you see films with millions in capital behind them yet they bomb at the box office!

In the end, the operators of those models won’t just stop there but will also harvest petabytes of data and store this for indefinite amounts of time, thanks to their exclusive ownership of the new means of production, as in those on-line services, their machine learning models, and the massive, energy-hungry hardware in data centres that they run on, maintaining their entrenched oligopolist positions in the market while wasting critical resources and emitting tons of carbon dioxide, inching us nearer every day to a catastrophic global demise, an extinction event.

I know these propositions sound bleak, with very little agency on our part. So is there something we can do about this predicament? As a matter of fact, yes. I think we don’t need to be fatalistic about this, which I will endeavour to cover thoroughly in my next article.