The title of Robert Ballagh’s painting The Thirtieth of January makes clear its connection to Goya’s The Third of May. But of course the visual language is also compelling.

While in Goya’s picture the outline of Madrid sets the location of the executions in 1808, in Ballagh’s it is the skyline of Derry, its walls, St Columb’s Cathedral, and the Presbyterian church, and indeed with Walker’s Monument still in place. Where there is a hillside behind the Spanish victims on the left of Goya’s picture, in Ballagh’s the eye moves upwards from the Bogside to working-class terraces.

In both paintings the focus is on the victims, the people against whom and on whose territory the atrocity is being committed. We see their faces, while the soldiers in both cases are faceless. Goya chooses the moment of execution; Ballagh shows us a scene directly after the shooting has begun. He shows us two victims, one dying, the other dead. We are faced with distressed people running, a press image that went around the world.

The priest, Father Edward Daly, holds up a white, blood-stained handkerchief, trying to shield this group carrying the first victim of the massacre, the mortally wounded Jackie Duddy, out of range. The people are clearly recognisable. They also hold white bloody handkerchiefs, underlining a peaceful protest crushed in blood. In Goya’s painting too a monk by the side of the rebel offers support, along with others.

A priest, Father Hugh Mullan, was among the dead at the Ballymurphy Massacre. There are many layers of associations.

Centred in the foreground is another victim, covered in white bloodstained cloth, echoing the handkerchiefs. The stark white, associated with peace, innocence, and martyrdom, reminds viewers of the brilliant white shirt of the man about to be shot in Goya’s painting. He is flanked on the right by a group of faceless soldiers, their weapons at the hip, indicating an indiscriminate aim. Another soldier on the left in a kneeling position closer to the body suggests “Soldier F,” who knelt to shoot dead Barney McGuigan as he waved a white handkerchief high above his head, trying to go to the aid of the dying Patrick Doherty.

“Soldier F” was responsible for a number of the cold-blooded killings, and the only one to be charged with murder—only to be cleared later. Perhaps because of this identity, we see his face in part.

Ballagh makes it clear that the marchers are unarmed. They are holding up placards; the two on the ground read Civil rights now and End internment. A Civil Rights banner occupies the upper centre of the picture, like a title.

The painting makes reference not only to Goya but also to Picasso’s Guernica, itself a picture about foreign invaders murdering a native population and also inspired by Goya. Like Picasso, Ballagh decided on a monochrome painting.

The covered dead man’s hand in the centre foreground still holds the broken end of the End internment placard, in much the same way that the slain man in Picasso’s painting grasps the broken sword. Picasso’s and Ballagh’s black-and-white executions evoke newspaper images; in Ballagh’s case most of the film from the event, and press photographs, were in black and white. The only colour is the blood-red splashes on white in his painting. The smoke behind the silhouetted demonstrators in the background suggests the use of tear gas, seen in so many photographs of police attacks on demonstrators.

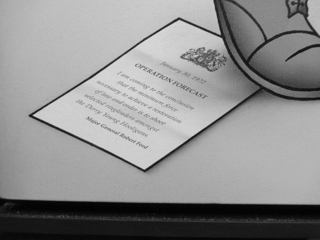

In the left corner, under the kneeling soldier’s heel, we see a sheet of official paper with the massacre’s military code name, “Operation Forecast,” dated January 30, 1972. Written on it are the words of Major-General Robert Ford: “I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders amongst the Derry Young Hooligans.” Ballagh leaves no doubt but that the killings were ordered at the highest level. In this respect too the painting goes further than any inquiry has ever done.

Art history and political history are connected. Art doesn’t exist outside time, and there is a tradition in art that does not shrink away from taking sides. This does not diminish the artist; think of Míkis Theodorákis and Pablo Neruda; and of course Goya’s The Third of May is one such work that has echoed through time. This painting inspired Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and the Massacre in Korea (1951); it has also been an enduring influence on Robert Ballagh’s work.

The power of this work, through Ballagh’s interpretation, was picked up by a community art group in Derry, which recently asked his permission to reproduce his The Third of May after Goya on a wall in Glenfada Park, one of the murder sites on Bloody Sunday. They did this because they could see the direct connection between the terror and the anger of their own experience and that depicted in The Third of May. In both pictures the viewer is a direct witness to the events and compelled to feel involved. Beside it, until recently, the group had displayed their copy of Picasso’s Guernica.

When artists take the side of the people against oppression they resonate and are understood around the world, because the condition of the victims of wars for profit, power and control is global. Bloody Sunday is a part of the world history of colonialism and occupation and of people’s resistance, and Robert Ballagh’s painting says just this, and demonstrates the necessity of art.