As retail investors launched a short squeeze on large hedge funds, forcing large stock-market movements and frenzied recapitalisation, many commentators heralded it as a victory for “the little guy” against Wall Street. However, the truth is far from that simple.

“The biggest owners of Gamestop: Fidelity (14%), Cohen’s RC Ventures (13%), and BlackRock (11%), and then a bunch of other mutual and hedge funds, and also a guy named Donald Foss who became a billionaire from a subprime auto loan company.”* These giant financial outfits are the real winners, as always.

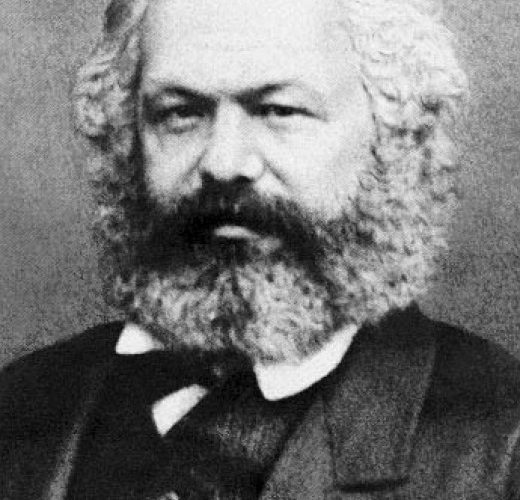

Also incorrect is the idea that this is some new departure, a uniquely modern phenomenon. As Marxists we should situate our analysis in history, and understand that this is just the latest manifestation of the transition of money from mere unit of exchange to “social symbol,” as described by Marx in the Grundrisse (chapter 3):

[Money] serves [the money holder] . . . only because of its social (symbolic) property; and it can have a social property only because individuals have alienated their own social relationship from themselves so that it takes the form of a thing.

Exchange value naturally remains at the same time an inherent quality of commodities while it simultaneously exists outside them; on the other side, when money no longer exists as a property of commodities, as a common element within them, but as an individual entity apart from them, then money itself becomes a particular commodity alongside the other commodities . . . Here a new source of contradictions which make themselves felt in practice. (The particular nature of money emerges again in the separation of the money business from commerce proper.)

It is this separation of “money business” from commerce proper that is the instructive part here. We can view the current economic situation on a continuum from the last major economic crisis in 2008. The current situation is directly influenced by the accommodations that capitalism was forced to make following the credit crunch that precipitated the crisis. With austerity enforced to rein in public spending, aiming to reduce states’ public debt liabilities, gut public services, and thereby (the hope was) invigorate private enterprise, fiscal remedies were out of the question. It was the turn of quantitative easing, and monetary policy, to attempt to get capitalism out of crisis.

Quantitative easing (QE) is the widespread purchasing, by central banks, of government bonds and other financial instruments. It has resulted in a huge inflation in asset prices since it was introduced, and has led to the largest stock-market rally in human history. It has also completed the transition of power from industrial capitalists to “money capitalists.”

In Capital (volume 1), Marx differentiates between the money capitalist and the industrial capitalist (productive capitalist). A money-owner uses their money as interest-bearing capital, by lending it to an industrial capitalist, thus putting it into circulation. After the agreed period, when the loan is repaid, the money returns to the money capitalist, as so-called realised capital.

The industrial capitalist uses the credit to employ workers to produce goods, creating surplus value. From the resulting profit they pay to the money capitalist the interest on the loan. Interest-bearing capital as a commodity arises from the fact that money is sold as capital at a price—interest.

The lender of money does not expend it in purchasing commodities, or, if this sum of values is in commodity-form, does not sell it for money. He advances it as capital, as M–Mʹ, as a value, which returns to its point of departure after a certain term. He lends instead of buying or selling. This lending, therefore, is the appropriate form of alienating value as capital, instead of alienating it as money or commodities. It does not follow, however, that lending cannot also take the form of transactions which have nothing to do with the capitalist process of reproduction.

We can see here that Marx foresees the emergence of an entirely parasitic rentier class, creating a system of transaction with little to no relation to production.

And this is a large component of the current situation of rampant speculative bubbles. Marx quite correctly showed that interest rates are defined by the total rate of profit. And with rates of profit now at a historic low point, we see historically low interest rates. It is the aim of asset inflation, by means of QE, to attempt to offset this historically low rate of profit—the compromise reached after 2008.

Since interest is merely a part of profit paid, according to our earlier assumption, by the industrial capitalist to the money-capitalist, the maximum limit of interest is the profit itself, in which case the portion pocketed by the productive capitalist would = 0. Aside from exceptional cases, in which interest might actually be larger than profit, but then could not be paid out of the profit, one might consider as the maximum limit of interest the total profit minus the portion (to be subsequently analysed) which resolves itself into wages of superintendence. The minimum limit of interest is altogether indeterminable. It may fall to any low.

Marx is also highly wary of the destructive power of speculation, with his harshest words kept for the rent-seeking behaviour of the money capitalist:

The relations of capital assume their most externalised and most fetish-like form in interest-bearing capital. We have here M–Mʹ, money creating more money, self-expanding value, without the process that effectuates these two extremes. In merchant’s capital, M–C–Mʹ, there is at least the general form of the capitalistic movement, although it confines itself solely to the sphere of circulation, so that profit appears merely as profit derived from alienation; but it is at least seen to be the product of a social relation, not the product of a mere thing. The form of merchant’s capital at least presents a process, a unity of opposing phases, a movement that breaks up into two opposite actions—the purchase and the sale of commodities. This is obliterated in M–Mʹ, the form of interest-bearing capital.

In the post-QE world there is no real relationship between asset prices and their underlying value. Money in effect is handed to speculators to play with as they wish, creating gigantic transactions but with no impact on the productive capacity of the underlying economy. Marx’s concept of “fictitious capital” is the key here.

Can you find a more perfect summary of the casino nature of the modern economy than the following passage from Capital (volume 2)?

The reserve funds of the banks, in countries with developed capitalist production, always express on the average the quantity of money existing in the form of a hoard, and a portion of this hoard in turn consists of paper, mere drafts upon gold, which have no value in themselves. The greater portion of banker’s capital is, therefore, purely fictitious and consists of claims (bills of exchange), government securities (which represent spent capital), and stocks (drafts on future revenue). And it should not be forgotten that the money-value of the capital represented by this paper in the safes of the banker is itself fictitious, in so far as the paper consists of drafts on guaranteed revenue (e.g., government securities), or titles of ownership to real capital (e.g., stocks), and that this value is regulated differently from that of the real capital, which the paper represents at least in part; or, when it represents mere claims on revenue and no capital, the claim on the same revenue is expressed in continually changing fictitious money-capital.

This is a very interesting situation, because this hyperfinancialisation is both the salvation capitalism is using to salvage itself from crisis and the seed of the next crisis. Marx puts it best when he says:

The credit system appears as the main lever of over-production and over-speculation in commerce solely because the reproduction process, which is elastic by nature, is here forced to its extreme limits, and is so forced because a large part of the social capital is employed by people who do not own it and who consequently tackle things quite differently than the owner, who anxiously weighs the limitations of his private capital in so far as he handles it himself. This simply demonstrates the fact that the self-expansion of capital based on the contradictory nature of capitalist production permits an actual free development only up to a certain point, so that in fact it constitutes an immanent fetter and barrier to production, which are continually broken through by the credit system. Hence, the credit system accelerates the material development of the productive forces and the establishment of the world-market. It is the historical mission of the capitalist system of production to raise these material foundations of the new mode of production to a certain degree of perfection. At the same time credit accelerates the violent eruptions of this contradiction—crises—and thereby the elements of disintegration of the old mode of production.

This “money capitalist” that Marx warned about in the nineteenth century is capitalism taken to its natural conclusion.

This idea of “late capitalism,” “financial capitalism” and so on is not a departure from Marx but is in fact just the new face on a very old system. In fact Marx says that this money capitalism is the true face of capitalism, as it doesn’t even pretend to be earned: it is nakedly extractive and parasitic, destroying the very lies that capitalism tells about itself. How else do we explain condemnation of the trading app Robinhood by an ubercapitalist like Ted Cruz?

Only one aspect should be emphasised and that is that the business of actual saving and abstinence (by hoarders), to the extent that it furnishes elements of accumulation, is left by the division of labour, which comes with the progress of capitalist production, to those who receive the minimum of such elements, and who frequently enough lose even their savings, as do the labourers when banks fail. On the one hand, the capital of the industrial capitalist is not “saved” by himself, but he has command of the savings of others in proportion to the magnitude of his capital; on the other hand, the money-capitalist makes of the savings of others his own capital, and of the credit, which the reproductive capitalists give to one another and which the public gives to them, a private source for enriching himself. The last illusion of the capitalist system, that capital is the fruit of one’s own labour and savings, is thereby destroyed. Not only does profit consist in the appropriation of other people’s labour, but the capital, with which this labour of others is set in motion and exploited, consists of other people’s property, which the money-capitalist places at the disposal of the industrial capitalists, and for which he in turn exploits the latter.

What is interesting about the Gamestop events is the ability to create a narrative of “us versus them.” Even if these are retail investors, and not financial organisations, they are probably only rarely members of the actual working class. It is the professional tech classes that are most likely to make up the majority of the Wall Street Bets contingent, forced to work from home during the pandemic, overpaid and underworked, with huge disposable income going unspent now that most commerce and travel is curtailed. It is these bored petit-bourgeois who are probably the real financial muscle for the current rally.

However, the bored should not be underestimated as a class of investor. Karl Marx wrote (letter to his uncle, Leon Phillips, 25 June 1864):

I have, which will surprise you not a little, been speculating—partly in American funds, but more especially in English stocks, which are springing up like mushrooms this year (in furtherance of every imaginable and unimaginable joint stock enterprise), are forced up to a quite unreasonable level and then, for the most part, collapse. In this way, I have made over £400 and, now that that the complexity of the political situation affords greater scope, I shall begin over again. It’s a type of operation that makes small demands on one’s time, and it’s worth while running some risk in order to relieve the enemy of his money.

*Andrew Granato, “Joke capital: Gamestop populism and the desire for narrative,” The Margins(tinyurl.com/1ovtglve).