“Tá dualgas ar gach saoránach Gaeilge a labhairt.” [“Every citizen has a duty to speak Irish.”]

These words of Máirtín Ó Cadhain, spoken in an earlier era of struggle, are finding new resonance in today’s Ireland. Across the nation, and particularly among the younger generations, a quiet but determined reconquest is underway. It is not, for now, an overtly revolutionary one, but currently manifests as a cultural and linguistic revival.

An Ghaeilge, once largely confined to Gaeltacht communities and the school curriculum, is experiencing a remarkable nationwide resurgence. This is not a mere short-term trend or a nostalgic fetishisation of the past. Within this cultural shift, a Marxist analysis reveals a profound response to the crises of contemporary capitalism: the housing emergency, the soaring cost of living under neoliberal political economy, the alienation of modern life, and the need to build a bulwark against the rising threat of the far right in our communities.

The cultural revival is an attempted reclamation of identity in a landscape where traditional markers of a successful life have become inaccessible. For a generation locked out of home ownership, burdened by extortionate rents, and facing precarious employment, the promise of bourgeois prosperity has been exposed as a lie. In this vacuum, the search for meaning and community turns elsewhere. The Irish language, once weaponised by a conservative native bourgeoisie in a state that served capital, is now being reclaimed as a symbol of resistance and a vessel for a different kind of Irishness—one not defined by property portfolios or subservience to the global market.

Marx famously argued that the economic base of society—the means of production and the class relations it generates—shapes the cultural and political superstructure. The current cultural revival is a superstructural phenomenon, but it is also a direct reaction to a societal base in profound crisis.

The housing catastrophe is the most visceral manifestation of this. When a basic human need like shelter is commodified to the point of impossibility, it shatters the foundational myths of the state. In this alienation, the Irish language becomes a counter-culture. It offers a form of social wealth that cannot be bought and sold by vulture funds—a shared history, a collective identity, and a sense of belonging that is not predicated on one’s postcode or bank balance.

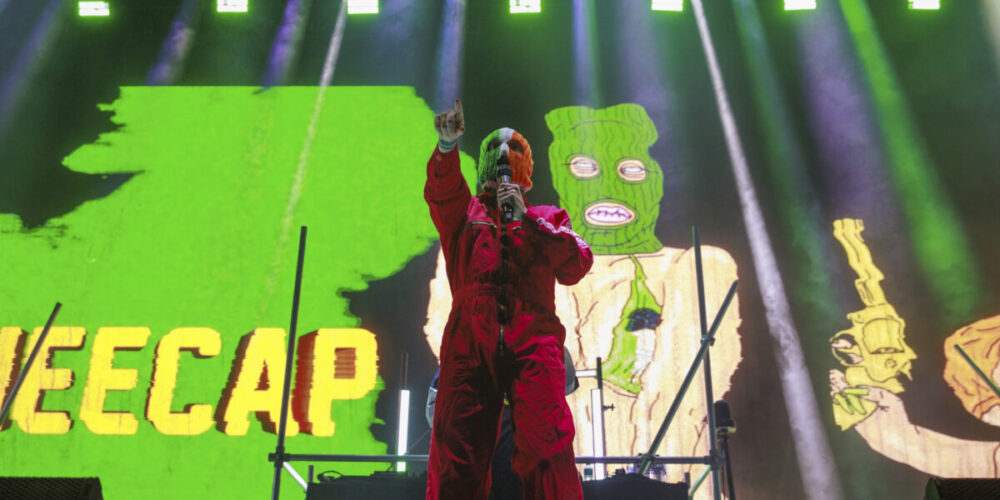

This is a class response. The ruling class in Ireland, both native and international, has always been happy to pay lip service to An Ghaeilge as a cultural ornament, while its economic policies systematically undermined the Gaeltacht communities that sustained it. The current revival, however, is youthful, grassroots and popular, exemplified by the Kneecap phenomenen. It is found in urban pop-up Gaeltachtaí, online language groups, and the determined efforts of ordinary people to learn and speak Irish.

As the crisis of capitalism deepens, the forces of reaction inevitably seek to channel popular discontent into the poisonous channels of xenophobia and nationalism. The far right in Ireland, a motley crew of conspiracy theorists, misogynists, criminals and bigots, attempts to pose as the defender of “Irish identity.” Yet, their vision of Ireland is a putrid, warped, exclusive one, often ironically devoid of the actual Irish language and culture they claim to protect.

The progressive reclamation of the Irish language stands in direct opposition to this. It is an inclusive nationalism, in the best revolutionary tradition of James Connolly. It understands that the culture of the Irish people is not a finite resource to be hoarded, but a living tradition enriched by engagement and solidarity. This concept of a native language, a birthright, is powerful. The socialist movement must argue that this birthright belongs to every worker in Ireland, regardless of their origin, and that the true enemy is not the migrant or refugee, but the native and international capitalist class that pits worker against worker.

The language revival offers a real community based on shared learning and collective struggle. It is our task to ensure this progressive impulse is guided by a clear, anti-capitalist politics. The revival of Irish culture is a positive and powerful development. However, Marxists must view it as dialectical. Culture alone cannot overthrow capitalism. A cultural revival that does not connect to the material struggle of the working-class risks becoming merely a new commodity, co-opted and sold back to us.

Our task is to unite the cultural revival with the political and economic struggle. The fight for the language must be part of the fight for public housing, for a living wage, for a health service that serves the people. We must build a movement that sees the Irish language not as a relic of a romanticised past, but as a tool for a liberated future. It should be the language of the picket line, the tenant union, and the community organisation, as well as Áras an Uachtaráin.

The reconquest of Ireland will be incomplete if it is only a reconquest of culture. It must be a reconquest of our land, our resources, and our economic destiny from the hands of the capitalist class. As the old certainties crumble, the yearning for a new society grows.

“Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam.” [“A country without a language is a country without a soul.”] Let us ensure that the soul of the nation envisioned by Pádraig Mac Piarais’ is a socialist one!