Over the first seven articles in this series, we demonstrated how public ownership, democratic planning, and socialist economics offer a compelling alternative to the chaos, inequality, and destruction of capitalism. But economic theory—no matter how coherent—remains inert without the political power to implement it. Equally, political power without a class-based economic programme devolves into empty populism or technocratic management. Only when economic and political struggle are united through the lens of political economy can the working class begin to reshape society in its own image.

This is the central strategic lesson of Marxism: that the working class cannot simply react to crises, nor rely on spontaneous resistance. It must organise politically. And that means building a revolutionary party rooted in theory, discipline, and the class struggle.

For Marxists, this political question is inseparable from the lessons of Lenin. In his seminal 1902 work What Is to Be Done?, Lenin argued that capitalism would not fall from economic collapse alone, and that workers’ spontaneous revolts—while inevitable—could be co-opted, diverted, or crushed without a conscious political force to lead them.

Against the disorganised amateurism of the Russian left at the time, Lenin proposed the need for a vanguard party: a disciplined, democratic, and militant organisation of professional revolutionaries capable of giving working-class struggles coherence and direction. The vanguard party is not an elite above the working class, but its most advanced detachment—those who have internalised Marxist theory, who connect daily struggles to systemic causes, and who are committed to revolutionary transformation.

This model is not some historical curiosity. It is more relevant today than ever. In the decades since the fall of the Soviet Union, the global left has largely splintered. Social-democratic parties like Labour in Ireland have capitulated to neoliberalism, giving up any class-based critique in exchange for careers in capitalist governance. Trotskyist and ultra-left groupings, meanwhile, often reduce politics to endless protest and moral outrage, lacking any long-term strategic orientation or organisational discipline.

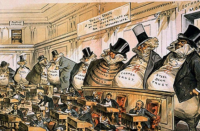

Meanwhile, we live under a highly centralised and coercive global capitalist order—dominated by US imperialism and enforced by the EU, NATO, and multinational finance. War, austerity, environmental degradation, and inequality are not “abuses” of the system. They are its logic. If the working class is serious about confronting this system, it must match the organisation of its enemy. That is the function of the Marxist-Leninist party.

A revolutionary party must be disciplined—not in the sense of authoritarian command, but in the sense of political clarity and collective strategy. Democratic centralism—often misunderstood—means open debate, democratic decision-making, and unified implementation. Without this, no revolutionary movement can survive the pressures of state repression, media distortion, or capitalist co-optation.

But discipline alone is not enough. Political education is central. Lenin famously wrote that “without revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary movement.” Revolutionaries must understand the system they are fighting—and must connect every struggle, from rent to racism, war to welfare, back to capitalism and the necessity of its overthrow. Without this clarity, action becomes reactive and fragmented.

In Ireland, this strategic clarity is urgently needed. The Irish ruling class is comprador in character—subordinate to foreign capital and the interests of imperialist blocs like the EU and US. Our politics is dominated by technocracy, clientelism, and consensus around permanent neoliberalism. Yet beneath this stagnation lies a working class increasingly alienated, increasingly overworked, and increasingly angry.

But anger alone is not power. It must be channelled. To do that, we must cultivate a revolutionary mindset—not as an abstract ideal, but as a lived political practice. Where the popular “growth mindset” centres individual success, the revolutionary mindset focuses on collective emancipation. It sees the working class not as victims or saviours waiting for the right leader, but as the only force capable of ending capitalism. It recognises that all actions—words, choices, and strategies—must aim to strengthen working-class power and weaken capitalist rule.

The revolutionary mindset is not confined to protests or meetings. It takes root in everyday life—in conversations with friends, family, and co-workers. It doesn’t rely on sloganeering, but on exposing capitalism’s contradictions through thoughtful questions and material examples. It seeks not to preach, but to awaken.

In the workplace, it pushes beyond economism. It shows how exploitation is structured, how industrial policies are shaped by profit, and how so-called “neutral” trade deals undermine workers globally. It recognises that trade unions must be political—not just defensive structures for wages, but vehicles for class power.

In the union hall, the revolutionary mindset challenges the status quo: why does our union not oppose imperialist wars? Why does it not demand public housing or climate action rooted in planning and ownership? Why is it silent on the very system causing these crises?

Those who adopt this mindset—those who connect theory to practice, and who devote themselves to building revolutionary organisations—are what Lenin meant by “professional revolutionaries.” They are not better or purer than others. But they understand that no spontaneous movement, no moral argument, and no viral outrage will dismantle capitalism without revolutionary organisation.

Ireland’s working class is still fragmented, and still politically disarmed. But it remains the only force capable of ending capitalist rule. If we are to win, politically active workers must become tribunes of the class—raising consciousness, forging unity, and organising power.

History gives us no guarantees. But it does give us lessons. Lenin’s contribution is not merely historical—it is strategic. The Marxist-Leninist party remains the most powerful tool the working class has ever created to win power. To ignore this is not realism—it is surrender.

From the Bolsheviks in 1917 to Cuba in 1959, from the Chinese revolution to Kerala’s local governance, class-conscious parties rooted in working-class struggle and disciplined strategy have reshaped history. We must study them—not to copy them, but to learn.

In Ireland, that means building political education programmes, intervening in trade unions, and constructing networks of local and workplace councils. It means uniting theory and practice, leadership and rank-and-file, and national strategy with grassroots mobilisation.