Last month, the Irish and British governments launched their joint Legacy Framework proposals. The stated aim is to provide families of Troubles-related dead with, “… a fair, proportionate, and transparent system to seek answers.”

This initiative is being described by both states as a means of undoing a flawed and discredited Legacy Act enacted by the previous Tory government. Whether this new set of proposals will turn out to be a significant improvement remains to be seen. Because, in spite of the usual pro-establishment spin, several issues remain unresolved.

There remains, for example, the matter of access to sensitive information. In many instances, this is a key element in determining exactly what role the British state played in the conflict. To what extent Britain’s intelligence agencies were involved in a secret counter-insurgency campaign remains an important question. However, it appears that little has changed in relation to this subject. The official British government press release <sup>[1]</sup> tells us this so-called new departure ‘… facilitates disclosure of the maximum possible amount of information to families consistent with the requirements of national security and to protect life.’

No doubt, the requirements of national security will take precedence over all other concerns. Conveniently, though, Britain’s Secretaries of State for the North will henceforth be spared the embarrassment of having to explain why such information is being denied to relatives of the deceased. The decision is being taken out of his or her hands but will be taken instead by a different branch of the state’s apparatus.

Furthermore, in keeping with protecting the interests of the British state, extraordinary precautions are being put in place to shield former members of its armed forces. Six special measures will be included in the legislation to be introduced in Westminster to specifically assist ex-soldiers, or veterans as they are referred to throughout the press release.

One of the measures, in particular, reveals how careful the British government is in dealing with the past. Point Three of six affords what it describes as protection in old age, stating that the health and wellbeing of witnesses (i.e., British military personnel) must be considered when deciding whether it would be appropriate to require them to give evidence. It is hardly facetious to describe this procedure as a ‘get out of jail free’ card, granting, as it does, the Ministry of Defence enormous latitude to decide who is to testify and who is best kept out of circulation.

Admittedly, there are certain aspects of this Legacy Framework that will be welcomed. The small number of inquests stopped by the previous legislation will be allowed to resume, while some others stalled while in progress will be referred for assessment by the Solicitor General. However, there will be no announcement of further new inquests. The new Legacy Commission, which is replacing the old and discredited ICRIR, will become the primary route.

There is, too, the fact that this is a joint initiative between the British and Irish governments, with input from the Republic’s authorities. Whether southern participation will hold the British fully to account remains to be seen. It is one step to identify a triggerman, but it is often still more important to identify who or what is overseeing the shooter.

Two examples will illustrate why this is especially relevant.

Writing 50 years after the Miami Showband massacre, survivor Stephen Travers <sup>[2]</sup> details the presence among the assassins of a man wearing a British Army officer’s uniform and speaking with an, ‘… educated, upper-class English accent …’. Since then, there has emerged a plethora of reports covering the actions of agents and informants working for MI5 across the range of armed underground organisations.

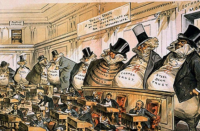

All of which clearly indicates that the northern Troubles were a much more complex affair than the narrative favoured by the authorities in both London and Dublin. A tendentious narrative tells of a conflict between the bad guys (terrorists) and the good guys (the state’s forces, maintaining law and order).

Were this merely a revisionist telling of history, then it might be best left in the hands of more objective historians to correct the story. However, the North is not an academic issue. An honest account of Britain’s deep-state machinations during the Troubles would do little to enhance the reputation of the old empire. What it would do, though, is generate a frank, open discussion north and south of the border about past events: who was pulling the strings, and for why. By moving the debate beyond the ‘baddies versus goodies’, a more progressive and peaceful environment would surely evolve in the North.

Whether the new Legacy Framework will deliver such an outcome is highly questionable. It is, nevertheless, such an important objective that no effort should be spared in making it a reality.