Ireland’s working-class communities have lived with the shadow of the drug trade for decades. From the heroin epidemic of the 1980s to today’s cocaine economy, drugs have carved deep scars through families, schools, and neighbourhoods. Entire generations were written off, while governments looked away.

Today, the problem remains as sharp as ever. Parents fear their children being recruited by gangs. Elderly residents are intimidated in their own homes. Communities are caught between the violence of organised crime and the indifference of the state. In this vacuum, the far right offers scapegoats, blaming migrants for social breakdown, while liberals retreat to empty slogans about “community policing.” Neither addresses the reality.

The Gang as an Alternative Economy

Television dramas like Love/Hate, Kin, or Top Boy fascinate audiences because they reflect something real: the gang as an alternative economy. For many young people alienated from school and shut out of stable work, the gang offers respect, belonging, and economic survival.

This is not simply about the lure of “fast money.” When education leads to precarious jobs or no opportunities at all, its value is diminished. Disenfranchisement becomes generational: parents who were failed by school pass on that cynicism to their children. The gang becomes not just a temptation but a cultural inheritance—a parallel route into adulthood.

Yet the outcome is almost always the same: violence, prison, or death. What appears as glamour is, in reality, the grinding down of working-class youth in the service of an underground economy.

Criminalisation and the Vicious Cycle

Instead of breaking this cycle, Irish state policy reinforces it. A young person caught with a small amount of drugs is criminalised, given a record that locks them out of work and education, and pushed further into the hands of gangs. The prison system acts as a revolving door, hardening the cycle rather than breaking it.

Other countries show different possibilities. Portugal, since 2001, has treated possession as a health issue, not a crime, pairing decriminalisation with serious investment in treatment. The result: reduced deaths, lower HIV rates, and no explosion in use. The Czech Republic pursued a similar path, coupling decriminalisation with harm reduction, and now reports some of the lowest HIV and overdose rates in Europe. Switzerland went further, offering heroin-assisted treatment for entrenched users, stabilising lives and reducing crime.

The lesson is clear: criminalisation fuels the problem, while health-led approaches reduce it.

Who Really Fuels the Market?

Public debate often treats drugs as a “working-class problem.” But who fills the coffers of the cartels? Not only young men in estates, but also the white-collar and middle-class users who treat cocaine as a weekend luxury. Wastewater analysis shows sharp weekend spikes in consumption, reflecting professional-class leisure patterns.

Working-class communities pay the price in violence and intimidation, while affluent Ireland pays the bills. The hypocrisy is stark: the poor are criminalised, while the rich are shielded from scrutiny.

The Global Alternative Economy

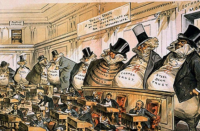

The drug trade is not a local issue but part of a global system. The UN estimates the global drug economy to be worth hundreds of billions annually. Irish gangs, such as the Kinahan network, are minor nodes in a much larger chain linking coca farmers in Latin America to smugglers in Europe, money launderers in banks, and investors in property.

These profits do not remain in the underworld. They flow back into the mainstream economy: into banks, offshore accounts, and real estate speculation. The IMF admitted after the 2008 crash that laundered drug money helped stabilise major banks. The so-called “alternative economy” is, in reality, deeply integrated into global capitalism.

The Lumpen Question

Marx described the lumpen proletariat—those excluded from stable labour, surviving on crime or hustling. In Ireland, disenfranchised youth increasingly fill this role. They are not born criminals; they are produced by a system that leaves them with no stake in society.

The long-term solution is clear: jobs, housing, education, and youth services. But communities also ask: what about now? Gangs terrorise families, juvenile prisons are overcrowded, and violence spreads.

Short-term, the answer is to direct firepower upwards, not downwards. Seize the assets of gang leaders. Disrupt laundering networks. Expand treatment, diversion, and restorative justice. Stop criminalising small possession. Protect communities by hitting the profiteers, not the children.

The Gardaí and the courts claim to defend justice. In reality, they defend property. They come down hardest on the small-time user or joyrider while leaving financiers, landlords, and profiteers untouched. Calls for “more policing” translate into harassment of working-class youth, not safety for communities. Real safety does not come from repression. It comes from solidarity, services, and organised community power.

A Marxist Response

A socialist response begins by rejecting the idea that addiction should be punished as crime. Small-scale possession must be decriminalised, because criminal records do nothing but lock young people out of work and education while feeding the prison system. Addiction should be recognised for what it is: a health issue that requires treatment, not incarceration.

That means building proper services—detox, rehabilitation, supervised injection facilities, and even heroin-assisted programmes where needed—so that people can recover, stabilise their lives, and escape the grip of gangs.

At the same time, the focus must shift away from punishing children at the bottom of the chain and onto those who profit at the top. The state has the power to seize assets, disrupt money-laundering networks, and dismantle the leadership of criminal enterprises. That power must be used against the kingpins, not against fifteen-year-olds with a bag of cannabis.

We must also puncture the hypocrisy that surrounds drug consumption. The cartels are not funded by kids in Ballymun alone but by the professionals in boardrooms and nightclubs who keep the demand flowing. Middle-class drug use must be named and challenged for what it is: the financial lifeline of organised crime.

And finally, no programme can succeed without tackling the conditions that breed crime in the first place. That means investment in housing, schools, and decent jobs—the foundations of dignity and security that gangs currently exploit in their absence.

A socialist Ireland would therefore confront the drug economy on every front: treating users with care, hitting profiteers at the top, exposing demand where it lies, and building the social infrastructure that can make the gang economy unnecessary.

Conclusion: No Easy Answers, But a Clear Direction

There are no easy answers. Communities under siege deserve relief now, but the ruling class offers only repression and scapegoating. The far right exploits fear to divide neighbours. Liberals offer shallow reforms.

Only a Marxist perspective locates crime in its real context: a capitalism that creates poverty, alienation, and profit out of misery. The drug economy is not separate from capitalism; it is one of its most parasitic expressions.

If we want to break the cycle, we must redirect anger upwards: against the profiteers, the launderers, the landlords, and the system that created the crisis. That is the task for our movement: to replace scarcity and despair with solidarity, dignity, and socialism.

The Scale of the Drug Economy

- €31 billion—the value of the retail drug market in the EU (2021), making it one of the largest criminal markets in Europe.

- 292 million people worldwide used drugs in 2022—roughly 1 in 18 adults.

- Cocaine production is at record highs, with Europe now the second-largest market after North America.

- Hundreds of billions—UNODC estimates place the global drug economy at close to 1% of world GDP.

- Banks benefit too—the IMF admitted that laundered drug money helped stabilise the global banking system during the 2008 crash.

- Ireland’s link—Irish gangs, including the Kinahan network, are tied into these global chains, laundering profits through property and business at home.

Bottom line: The drug economy is not a “street corner” problem. It is a global system of profit that enriches elites while devastating working-class communities.