Fun fact: Guinness, the quintessential Irish drink exported worldwide, originated in the working-class pubs of early 18th-century London. Known as porter, this dark beer was invented as an affordable, nutritious, and consistent alternative to the custom-mixed blends patrons often bought. Its name came from its immense popularity with London’s dockworkers and market porters. Brewed with charred malt and extra hops, porter was durable enough for long sea voyages, making it a perfect commodity for Britain’s naval empire.

When this popular London import reached Dublin, it was an instant success. Arthur Guinness, who bought a disused brewery at St. James’s Gate in 1759, was not the first local porter brewer – Dubliners like James Farrell, guided by London-trained John Purser, were producing it by the mid-1770s. Guinness adapted quickly, brewing porter from 1778, dropping ales by 1799, and from the 1820s, his successors marketed stronger versions as “stout porter,” and later, simply “stout.” By 1779, Arthur had secured the lucrative Dublin Castle contract, ensuring his brewery’s growth. Guinness’s real legacy was copying porter on a large scale.

Born 300 years ago, Arthur Guinness (1725–1803) had indigenous Irish roots, though his family had converted to Protestantism. Not part of the elite, he belonged to a striving middle class that used education, strategic marriages, and commercial acumen to advance within British colonial society. He identified as a Protestant Irish patriot – supportive of Catholic emancipation, and loyal to Ireland – yet remained a pragmatic businessman who worked within the system to achieve success.

His life unfolded under the Penal Code, a system designed to keep the Catholic majority politically powerless, economically constrained, and socially humiliated. Catholics were barred from voting, owning valuable property, receiving an education, or freely practising their faith. This oppression forged a resilient Irish identity, with clandestine resistance preserved in hedge-schools and by priests.

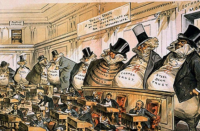

Guinness’s commercial ambitions were constrained by England’s colonial policy, which dismantled Irish manufacture, trade, and industry through laws like the Wool Act. Prosperous Irish exports were stifled to eliminate competition, crippling the economy. A corrupt, English-controlled Irish Parliament enforced this system, leaving tenants and labourers on subsistence diets while producing goods for export. Famine was frequent. As Jonathan Swift’s satire highlighted, landlords “devoured” the people, creating a nation on the brink of starvation.

Swift, a key figure of the Enlightenment, employed reason and satire to lampoon the colonial system as cannibalistic – most famously in A Modest Proposal (1729) – and outlined the imperative of an indigenous Irish economy in works like The Drapier’s Letters (published between 1724-25; the most famous fourth letter: A Letter to the Whole People of Ireland). Writing under the pseudonym of a simple shopkeeper, he created a relatable national hero who galvanised public opinion against exploitative measures such as William Wood’s inferior copper coinage. Swift thereby contributed to forging a national Irish identity, appealing across class and sectarian lines to a “whole people of Ireland,” united against a common oppressor. In Gulliver’s Travels (1725), Swift even anticipates a successful revolution in Ireland. This is seventy years before the United Irishmen!

Both Swift and Guinness were Protestants, but their approaches differed. Swift acted as a moral critic, railing against colonial rule. Guinness embodied the benevolent patriarch. His philanthropy—providing healthcare, supporting hospitals like the Meath, co-founding Ireland’s first Sunday School, and later offering pensions, and housing—was both genuine and pragmatic. A healthy, loyal workforce was productive. While Swift shamed the elite, Guinness offered paternalistic care within the system, addressing public problems privately without challenging underlying inequalities.

Guinness practised patriotic pragmatism. He opposed the Penal Laws and supported freer trade and legislative independence for the Irish Parliament in the 1780s. As a member of the “Kildare Knot,” a provincial branch of the Friendly Brothers of St. Patrick, he identified as Irish, yet worked within the system—favouring reform over revolution. He did not support the United Irishmen’s 1798 epic uprising; his vision was gradual electoral reform. He benefited from the same system that generated grievances behind the rebellion, keeping his progressive ideals largely aspirational.

Guinness’s philanthropy reflected the Protestant ethos of “good works.” He made loans to charities without expectation of repayment and served as unpaid treasurer of the Meath Hospital for decades. Subscribers could send patients for treatment, benefiting his workforce and foreshadowing the brewery’s later clinics. This combined charitable intent with enlightened self-interest, fostering goodwill while addressing genuine needs within the constraints of the time.

Arthur Guinness’s legacy is thus dual: he was a product of the colonial system whose actions alleviated some of its harshness, even as he ultimately upheld its structures.

Shock fact: from 1799 to 1939, Guinness was Ireland’s largest private employer. Today, however, the brand is owned by Diageo – a British multinational created in 1997 through the merger of Guinness plc and Grand Metropolitan. In the process, Guinness’s once-vaunted worker welfare – housing, healthcare, pensions – was phased out by the late 20th century. Diageo’s record since has been one of cost-cutting, brewery closures, and job losses. It even sat on the board of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), helping to shape corporate-friendly tax and liability laws, before quitting under public pressure in 2018. What was once a paternalistic brewery at the heart of Dublin is now an anti-working-class multinational that prioritises shareholders.