In past centuries, Ireland endured one of the harshest colonial experiences in European history. During the British era, Irish farmers saw their lands confiscated and were forcibly displaced from their farms to make way for Protestant settlers from England and Scotland. This policy—known as the Plantation Policy—entailed the large-scale seizure of native Irish land and the expulsion of its inhabitants. It was not merely a form of political punishment but rather a systematic plan to alter the demographic composition and secure complete control over resources, to the point where the Irish presence in their own land was threatened with extinction.

Today, centuries later and thousands of kilometres away, the world witnesses the same policy being replayed in the West Bank under what is known as the Annexation Policy. The Israeli occupation is carrying out a sweeping settlement project that relies on land confiscation, settlement expansion, restrictions on Palestinian life, and forced displacement—particularly in Area C, which constitutes more than 60% of the West Bank and where Palestinians are prohibited from exercising any real authority.

According to a July 2025 report by the Al-Baider Organization for the Defense of Bedouin Rights and Targeted Villages, over 320 direct attacks were documented in a single month against West Bank communities and villages—carried out by the Israeli army and settler militias, with concentrations in the Jordan Valley, Jerusalem, and southern Hebron. These attacks included road closures, home demolitions, agricultural land seizures, and physical assaults, leading to the forced displacement of dozens of families. The report stresses that such acts are not isolated incidents but part of a deliberate policy aimed at emptying the land of its native inhabitants.

In Ireland, the ultimate goal of the Plantation Policy was to permanently reshape the demographic structure and claim the land forever. This is precisely what Israel is doing in the West Bank through a policy of creeping annexation that involves:

- Expanding settlements and linking them through exclusive road networks.

- Restricting or completely prohibiting Palestinian construction.

- Transferring thousands of new settlers into strategic areas.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) describes this pattern as “creeping annexation”, a view echoed by international legal experts who see it as a blatant violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

A historical comparison between the Irish and Palestinian experiences reveals deep structural similarities. In 17th-century Ireland, British colonial authorities sought to dismantle the geographical and social bonds between native communities and their land, replacing them with loyal settlers under the umbrella of plantation.

In today’s Palestine—particularly in the West Bank—Israel is employing a similar approach: removing Palestinian residents and replacing them with Israeli settlers backed by direct political and military support. Field evidence from Area C shows the implementation of this creeping annexation strategy through the construction of new settlement roads, the expansion of outposts, strict building bans on Palestinians, and the relocation of thousands of settlers into these areas. These measures mirror what Irish fields and villages suffered centuries ago—ethnic cleansing, land confiscation, and the settlement of newcomers under the protection of a ruling power at the expense of the indigenous population.

The Irish experience teaches that settler colonialism, no matter how long it endures, leaves behind a heavy legacy of resentment and conflict that can only be resolved by recognizing the historical rights of the native people and returning the lands seized from them.

In the Palestinian case, ignoring these roots, including land confiscation, population displacement, and demographic engineering, serves only to prolong the conflict and deepen cycles of violence. As historian Ilan Pappé has argued, the settlement structure is not a secondary aspect of the conflict but rather its core driver; therefore, any peace or settlement initiative cannot achieve credibility or viability if it ignores this structural dimension of dispossession and colonization.

Conclusion – In the Name of Humanity

Area C of the West Bank, including the Jordan Valley, has today become the stage for gradual annexation, whether through settlement construction, infrastructure integration into Israel, or the conversion of farmland into closed military zones. This policy is not far removed from what the Irish endured when their fields and villages were seized and handed over to new settlers, while the original landowners were driven into poverty and exile.

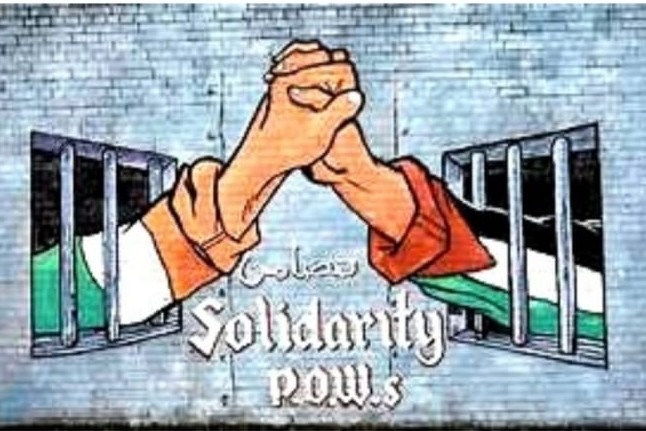

For the Irish, scenes of olive trees uprooted in Hebron, homes demolished in Jerusalem, or shepherds chased in the Jordan Valley are not distant images from a foreign struggle; they are a living reflection of what their ancestors once faced. Ireland’s national memory, shaped by the pain of occupation and the resilience of resistance, makes solidarity with Palestine not merely a political stance but a natural extension of their own liberation experience.

In Ireland, the collective memory of life under occupation shapes a deep moral bond with Palestinians. When Irish eyes witness homes being demolished in Jerusalem or olive groves being torn from the earth in Hebron, they recognise a story their land once lived.

Today, the message to Ireland is clear: standing with the Palestinian people is not just a political choice—it is a moral and historical commitment. Just as the Irish once stood against the British Empire to defend their land and dignity, their support for Palestinians today is a defense of the same principles: freedom, justice, and the right to the land, in the face of a colonial project that, while updated in its methods, retains the same essence.

As President Michael D. Higgins urged, we must “stop watching hunger and destruction” and activate Chapter VII of the UN Charter. His words resonate with a shared moral imperative to confront colonialism, past and present.