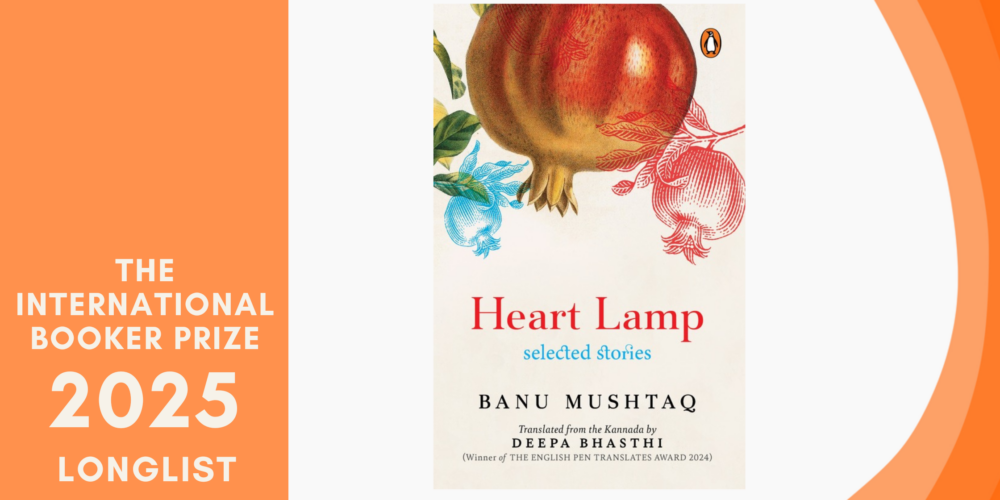

When Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp became the first Kannada work—and first short story collection—to win the 2025 International Booker Prize, it marked more than a literary triumph. It marked a pivotal recognition of regional Indian literature and brought overdue attention to the voices of Muslim women in rural Karnataka. Translated by Deepa Bhasthi, who retains the cultural texture and linguistic richness of the original, Heart Lamp is a radical act of witnessing. Across twelve stories spanning three decades, Mushtaq reveals systemic oppression while offering her characters—mostly Muslim women—a language of resistance.

A major voice in Karnataka’s Bandaya Sahitya (Rebel Literature) movement, Mushtaq confronts caste, class, gender, and religious oppression. She speaks out against triple talaq (a now-banned instant divorce practice) and hijab bans that restrict Muslim girls’ education, while also critiquing conservative patriarchy within Muslim communities. Her work bridges Bandaya’s class-caste rebellion with Islamic feminism, exposing how Hindu nationalist policies and patriarchal religious practices together suppress women’s autonomy. By collaborating with Dalit-Bahujan groups and Muslim women’s collectives, Mushtaq expands the scope of Rebel Literature to resist both Islamophobia and internal injustice.

Mushtaq’s stories are grounded in her identity as a Muslim woman rooted in faith but critical of its misuses. Her political and literary voice was shaped in the 1970s Bandaya movement, which rejected elite literary norms in favour of protest-driven narratives from the margins. Her focus, however, remains distinct: the intersecting constraints faced by Muslim women due to class, caste, gender, and dogma.

Her stories reveal how patriarchy operates through the fusion of religion and state power. Hindu women contend with caste-bound honour systems, while Muslim women face erasure enforced by groups like the Tablighi Jamaat and mosque mutawallis: clerics who manipulate scripture to maintain control. In Black Cobras, women denied justice by a hypocritical mutawalli curse him with symbolic venom; his wife eventually rebels, briefly but powerfully revealing the vulnerability of patriarchal authority. Mushtaq’s realism resists fantasy: the women don’t overturn the system, but their resistance lingers like a cobra’s venom: ultimately deadly.

Her critique, however, extends beyond India. While she denounces Indian patriarchy, she never romanticises Western ideals. In The Shroud, a wealthy woman on hajj forgets to buy a burial shroud for a poor widow who entrusted her with money. In another story, a high-heeled shoe is unbearably tight on a pregnant woman, symbolising the discomfort of imposed modernity. In A Taste of Heaven, Pepsi Cola is used to deceive an elderly woman into believing it’s the drink of paradise. For Mushtaq, liberation must be grounded in lived reality, not in regressive tradition nor shallow Western mimicry.

Economic dependency is another prison. Many women in Heart Lamp are at the mercy of their husbands for survival. A second wife becomes an existential threat in more than one story. Class is a constant undertone. Mushtaq critiques not just personal failings but a system in which the wealthy perform piety while neglecting the material needs of the poor. In Red Lungis, a wealthy Muslima organises a mass circumcision, other stories mock the hypocrisy of the well-to-do with biting irony.

Mushtaq’s stories reflect constrained lives and systemic injustice, though resistance persists in subtle forms. A tubectomy in Black Cobras, a matchstick in Heart Lamp—these acts hint at rebellion. Change is not immediate, but seeds are planted.

One of Mushtaq’s most radical acts is linguistic. The hybrid Kannada-Urdu-Dakhni fabric of Heart Lamp is a rebellion against literary elitism. Bhasthi’s translation preserves this vernacular richness, maintaining the integrity of rural Karnataka’s Muslim voices. The collection’s multilingualism is political, rejecting any monopoly on narrative. In this, Mushtaq and Bhasthi follow in the footsteps of writers like Ngũgĩ, who resist the hegemony of English to reclaim cultural narrative through the vernacular.

In Heart Lamp, objects become silent witnesses to oppression. The kerosene lamp in the title story isn’t just a threat of death but a mute accuser of a society that drives women to despair. The forgotten burial shroud, the too-small shoe, the Pepsi Cola—all evoke systemic cruelty through metaphor. In Black Cobras, the serpents never appear—the venom lives in the women’s curses. A matchstick, a school uniform, a cooking pot: each carries the weight of lives denied freedom. These objects ensure that, even when women’s voices are silenced, evidence of injustice remains.

Even the structure of Heart Lamp is radical. Unlike traditional collections that build toward resolution, Mushtaq’s stories mirror the unresolved crises of her characters. The narratives leap between 1990s rural Karnataka and today’s cities, showing that the same struggles persist, only in different guises. Closure is consistently withheld—a reflection of lived reality.

The spirit of Bandaya Sahitya courses through the collection, but Mushtaq transforms its legacy into something uniquely hers. In Black Cobras, collective defiance—not heroic individuals—brings hope. In Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord!, she subverts religious language itself, turning Allah’s name into a cry against patriarchal readings of faith.

As the Booker jury noted, Heart Lamp transcends its region precisely because of its rootedness. In giving voice to Karnataka’s most marginalised women, Mushtaq speaks a global truth to power. As she said in her acceptance speech: “No story is ever ‘small’—in the tapestry of human experience, every thread holds the weight of the whole… Literature remains one of the last sacred spaces where we can live inside each other’s minds, if only for a few pages.”