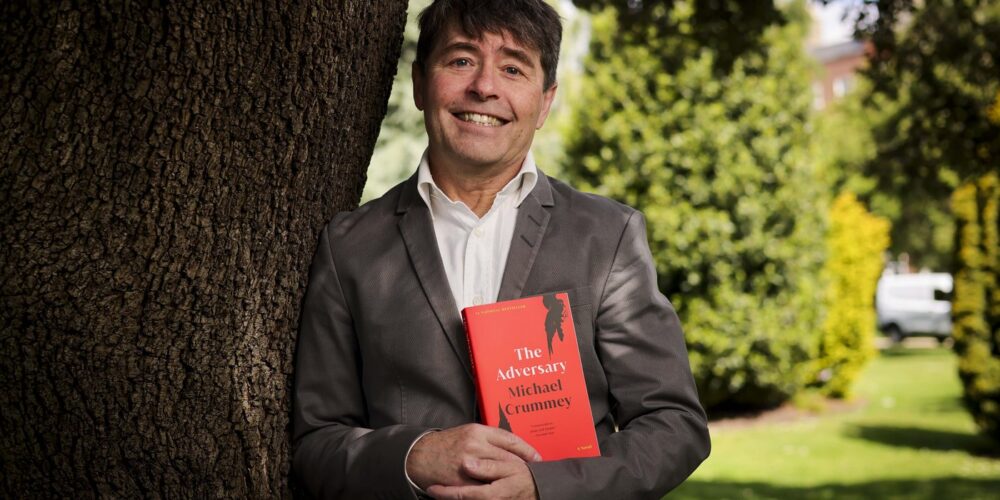

Michael Crummey’s The Adversary, winner of the 2025 Dublin Literary Award, is a dark, atmospheric novel that probes the brutal complexities of early colonial Newfoundland through themes of power, class, and survival. Set in a remote coastal community marked by hardship and hierarchy, the narrative interrogates the moral and human costs of empire, patriarchy, and capitalist extraction.

Set in the early 19th century, Newfoundland is portrayed as a frontier colony defined by British imperial rule, the Church of England, and struggling settler communities. References to the King’s army and Hanoverian military root the story in an era of imperial expansion. Fears of “American marauders” and sentinels on watch reflect historical tensions—borderland anxieties and the spectre of US aggression.

At the novel’s core is a scathing critique of the colonial capitalist class, embodied by Abe Strapp and his cunning rival sister, the Widow Caines—a twisted echo of Cain and Abel. Both represent elites who extract wealth through the exploitation of land, labour, and the dispossessed. Crummey explores how economic power is sustained through social violence and dependency, mirroring broader patterns of imperial inequality. The unforgiving Newfoundland landscape—its storms, sea, and plagues—reflects the social order’s cruelty and relentless demands. The cold is not only environmental but internalised, creating a sense of inevitable entrapment.

Among the novel’s most compelling elements is its attention to female perspective, particularly through the Widow Caines. A figure of resilience and manipulation, she supports the poor selectively but ultimately serves her own capitalist ambitions. Though nominally a Quaker, she corrupts that community’s egalitarian values for personal gain. Her betrayal of Solemn, motivated by a private vendetta, reveals how class overrides gender. Other women—healer Mary Oram, teacher Relief Picco, and servant Bride Lambe—see through her ambitions and embody moral clarity.

Crummey also gestures toward Indigenous presence and colonial racism, with references to the Inuit (“Esquimaux”), Beothuk (“Red Indians”), and the Haitian former slave, Dominic Laferrière. While most characters reflect the period’s racism, Captain Truss’s lack of prejudice and respect for Indigenous people offers a counterpoint. Though subtle here, this reclamation of dignity aligns with Crummey’s broader project of challenging historical erasure.

Crummey’s use of 19th-century English and regional Newfoundland expressions immerses readers in the time and place. This textured language reinforces the novel’s central concern: the rot at the heart of colonial power, embodied in the ruling class’s excesses and depravity. One such scene unfolds in Abe Strapp’s mansion, the Big House, transformed into a brothel-casino-salon and exemplifies the complete moral degradation of the colonial masters, combining drunkenness, gambling, sexual exploitation, and nationalist posturing.

The scene of Inez Barter’s humiliation—a moment best left unspoiled—exposes the complicity of bystanders and the normalisation of cruelty. The scene evokes the work of Chingis Aitmatov, where degradation and inhumanity are mirrored in people’s treatment of animals and the weak. Equally disturbing is the “mumble a sparrow” contest—a grotesque, bird-biting competition that serves as a microcosm of colonial violence and social degradation. Here, violence becomes entertainment, a perverse test of masculinity, exacting a deep moral cost on both participants and spectators.

These vignettes strip away the veneer of civility, revealing a culture of cruelty and consumption. Women are commodified, innocence debased, and pleasure extracted from pain. Crummey’s bitter satire lays bare the violence at the core of empire and capitalism, where power depends on degradation and the erosion of ethics.

However, resistance, too, is present in The Adversary — largely subdued and perilous, often met with harsh, public punishments designed to crush dissent and instil fear. One brutal whipping towards the end of the book, meant to enforce obedience through terror, marks a turning point. The local community, previously passive onlookers, are now outraged by the injustice and cruelty, transforming the scene into a catalyst for collective defiance. This eruption of resistance reveals a common yearning for justice and dignity, even in a society where defiance is dangerous and often devastating. Through this episode, Crummey underscores how resistance, however quiet or fleeting, persists beneath the surface of oppression, offering hope amid relentless brutality.

The novel’s title, The Adversary, is deliberately ambiguous. It stands as a symbol of capitalist colonialist class interests and the myriad agents who serve them, crushing human nature, empathy, and goodness in their wake. Crummey centres the story on the Widow Caine, Abe Strapp, and those caught in their orbit, offering a nuanced, often female-focused exploration of exploitation, complicity, and resistance.

Crummey acknowledges the novel’s darkness, admitting the world he portrays is “probably a lot darker than the reality of the time.” But he justifies this by pointing to contemporary parallels: “What I decided I was going to do was take the worst of the world as we have made it and compress it all down and have it play out in this tiny community in Newfoundland 200 years ago.” His horror at rising authoritarianism—particularly in the United States—informs the novel’s urgency.

The Adversary is thus more than historical fiction. It is also a modern parable, challenging readers to confront the legacies of empire, the dangers of capitalist power, and the possibilities of resistance. It warns that the adversaries of justice—greed, violence, and apathy—are not confined to the past, and that reckoning with history is also a reckoning with the present.