Marxists know well the state is not a neutral arbiter but a mechanism for managing the affairs of the capitalist class. While the state may exhibit relative autonomy, that is, it can act independently from capital, it functions, in the last instance, to reproduce the conditions for accumulation, whether state actors realise it or not. In the tradition of Greek Marxist Nicos Poulantzas, the state is structurally compelled to sustain the conditions for accumulation. As a key organ of financial capital vis-à-vis the state, the bond market exercises substantial disciplinary power in this context.

Take recent events in Trump’s tariffs. His policies include protectionist trade moves that challenge the interests of transnational wielders of footloose capital. Yet his leash has been recently tightened, in this case by the financial sector. The recent announcement of sweeping tariffs led to sharp sell-offs in U.S. government bonds, causing interest rates (“yields”) to surge. The 10-year Treasury yield experienced its most significant weekly increase since 2001, while the 30-year yield saw its most significant rise since 1987. Such movements indicate capital’s concerns about tariffs eroding profitability, particularly in this case, the concerns of private Japanese investors and over-leveraged hedge funds (“Tariff chaos leaves its mark on US debt costs”, Reuters, 14 April 2025; “Foreign Private Sector Holds Key to US Treasuries”, Reuters, 15 April 2025). The bond market, representing the aggregate interests of a powerful strata of transnational capital, acted as a disciplining force, steering policy away from actions detrimental to profitability. Hence, the delay/watering down of tariffs. As one asset manager reported to the Financial Times:

“I think this has proven that he (Trump) pays attention to the markets and that he realises when he’s gone too far. I think that’s a plus for the guardrails: the market still has power” (“Why did Donald Trump Buckle?” 10 April 2025).

That has implications for the Left. The “guard rails” of finance capital become an immediate and existential constraint for leftist governments, especially those pursuing redistribution, nationalisation, or ruptures with austerity. When such governments borrow to invest in social programs or infrastructure, the bond market demands higher yields or dumps the currency. A fiscal crisis of the state follows.

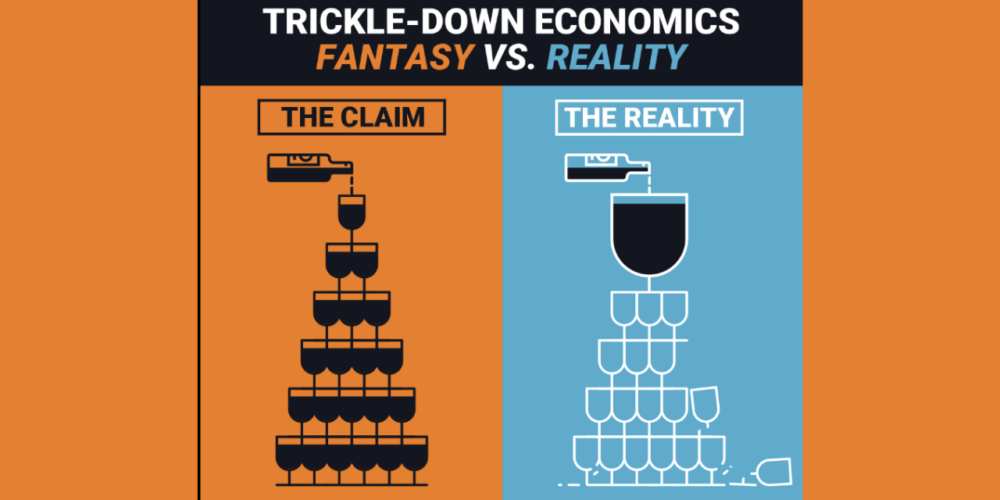

To break the dictatorship of capital and those who live by “clipping coupons”, Communists can’t just govern differently within capitalist structures. Tinkering with taxes – a.k.a. “tax the rich” – not only won’t work but won’t change the fundamental relationships.

Communist strategy is to break the rule and fetishisation of money, re-establishing democratic control over investment and production, and coordinating internationally to confront global finance. That means facing the bond market tactically and as part of a broader strategy to transition to socialism. Left governments would need to reimpose controls on capital flows to prevent speculative flight and regain policy space. That can include regulating foreign exchange markets, restricting speculative short-term capital, and banning foreign ownership of government debt.

In that context, Communists would bring the banking sector and credit allocation mechanisms under public, democratic control. A socialist state could create a sovereign public credit system, issuing debt to itself and channelling investment according to social needs, not profit. While issuing its own debt brings risks, it challenges the bond market by removing the state’s dependence on private creditors.

The Communist strategy thus involves monetary sovereignty – the ability to issue and control currency – and ultimately a shift to planning over markets in key spheres. A transitional program might include debt moratoria or debt repudiation. Sure, one country acting alone faces massive retaliation. In theory, a coordinated bloc of socialist states is preferable to pool resources, trade in local currencies, and provide each other with financial support.

This is currently not on the agenda, certainly in Ireland, while the unreliable, heterogeneous and self-preserving BRICs are no Comecon. That might mean more modest steps to build working class confidence in the first instance: but again, that’s why it’s called “the struggle”, for it was never meant to be easy.