The German Peasants’ War (1524–1525) was a large-scale social and political uprising in early modern Europe, where peasants, who constituted the majority of the population, revolted against the oppressive feudal system. Trapped in servitude, the peasants were burdened with labour and levies to the nobility while a growing bourgeois class in cities, although economically significant, was politically suppressed.

Before the Peasants’ War, earlier movements such as the Bundschuh (a peasant organisation) and the Poor Conrad uprising demonstrated a growing willingness among peasants to resist exploitation. These movements, although local in scope, shared the demand for social and economic justice and rejection of feudalism. The German Peasants’ War was part of a broader European trend of peasant unrest in countries like France, England, and Spain. Despite its eventual failure, the war contributed to the dissolution of the feudal system and laid the groundwork for the development of early capitalist societies.

The Reformation played a crucial role in these uprisings, particularly with the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages, which challenged the established religious order and made Scripture accessible to the masses. The invention of the printing press further amplified this impact. Artists of the time also had access to these texts and used them as tools of resistance, advocating for a more direct relationship with God.

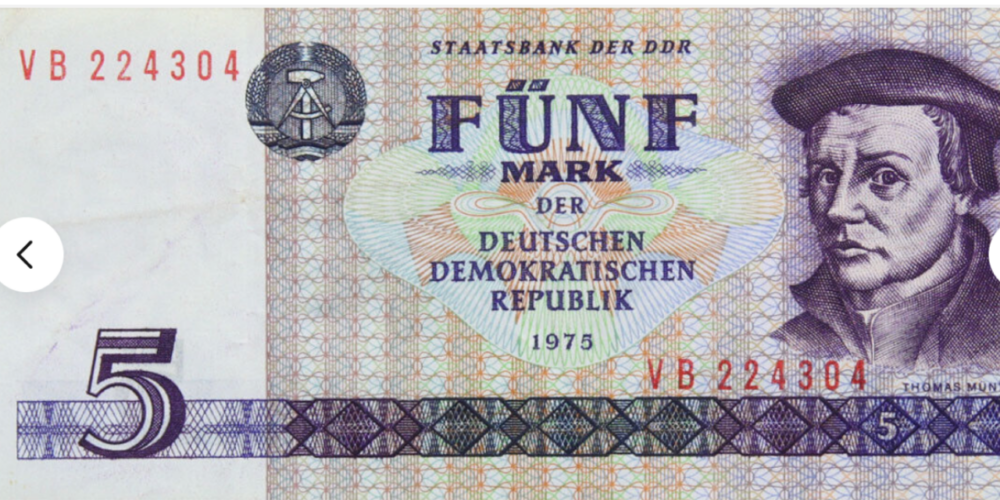

The Peasants’ War began in 1524 in southern Germany and quickly spread to other regions. The peasants’ demands were outlined in documents like their Twelve Articles, which called for the abolition of serfdom, reduced taxes, and the free election of pastors. Their grievances were both religious and social, set within the context of the Reformation, which opposed the power of the Catholic Church and the feudal system. However, the bourgeoisie, fearing radical change, sided with the princes, leading to the peasants’ brutal suppression, deepening the divide between the bourgeoisie and peasants. The war ended at Frankenhausen (15 May 1525), where peasant forces under Thomas Müntzer were defeated. Müntzer was captured, tortured, and beheaded.

Years before the peasants’ defeat, several artists of the time supported their cause through their work. Among them, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) stands out as the first German artist to recognise peasants as aesthetic subjects. His famous copper engraving Three Peasants in Conversation is far more than a simple depiction of country folk in their mature years. It is a multifaceted work of art deeply rooted in the social and political tensions of its time: a time when the Bundschuh was already active. Parallel to this, the humanist movement shaped the intellectual landscape, with Erasmus of Rotterdam as one of its leading figures. His writings on social justice and his criticism of the Church and society were also known among the rebels.

In Dürer’s engraving, the weapons of the men on the left and right immediately catch the eye. The sword of the man on the left—judging by his clothing and headgear, likely an urban craftsman—runs almost exactly along the central axis of the engraving and takes up nearly half the height of the image. The central position of the sword underscores the impression of a new self-confidence and resolution among the people. The sack slung over his shoulder suggests that he is on the move. Beneath his tunic, a shirt is visible. The peasant on the right also carries a knife on his belt. His ominous long leather boots with spurs form a humorous contrast to the eggs he carries in his basket, perhaps on his way to or from the market. His headgear—a medieval-looking hood with a fur hat worn over it—suggests someone who works outdoors.

Another striking detail is the turbaned man in the centre of the image. The turban in Dürer’s time often symbolised scholars or artists (Dürer portrayed his master Wolgemuth with a turban). The man could thereby represent a humanist who, through his ideas, writings, or artwork, supports the resistance against the ruling order. In connection with the peasant movement, he could be interpreted as helping fuse theory and practice. His hand reaching into his breast pocket, as if pulling out a document, reinforces this impression. His weapon is of a different kind but still significant. Dürer does not simply depict the men as working folk but as revolutionary figures.

Dürer’s Three Peasants in Conversation (c. 1497) was part of a broader effort to humanise and empower the peasant class. His work reflected the ideals of the Reformation, particularly the emphasis on individual agency and the rejection of hierarchical oppression.

Other artists also depicted the common people in their work, and even risked and gave their lives for the peasants’ cause. Mathis Grünewald (c. 1470–1528) used his Isenheim Altarpiece to portray Christ’s suffering as a metaphor for the oppressed. Tilman Riemenschneider (c. 1460–1531), a sculptor and mayor of Würzburg, aligned with the peasants and suffered arrest and torture after their defeat. Jörg Ratgeb (1480–1526), a painter and elected peasant chancellor, critiqued ruling-class violence in his Herrenberg Altarpiece, leading to his execution.

Despite the peasants’ military defeat, this war was never forgotten. It remains the first class war to challenge the feudal order in Germany. Artists like Dürer, Grünewald, Riemenschneider, and Ratgeb used their work to resist injustice, documenting their era’s struggles and preserving hope for a better world.

Their sacrifices highlight the cost of resistance, yet their enduring art remains a testament to the power of creativity in advocating for justice. Their courage continues to inspire the fight for human dignity and freedom, proving that the struggle for justice is never in vain.