Ar dtús, caithfidh mé mo leithscéal a ghabháil as labhairt anseo i dteanga ár namhad. Nach greannmhar go bhfuil muid ag plé an ábhair seo i dteanga a níonn scrios ar ár gcultúr agus ar mheon na saoirse sa tír seo agus ar fud an domhain, lá i ndiaidh lae. Domhsa, léiríonn sé seo, ní amháin chomh láidir agus chomh fíochmhar is atá an t-impiriúlachas, a d’éirigh leis, teanga agus cultúr níos sine agus níos binne a shárú ach chomh tábhachtach agus chomh lárnach is atá an athbheochain i streachailt ar bith a bheirfidh sinn slán amach ó bhruach na hainnise seo ar a díbríodh muid, sé sin braighdeanas an impiriúlachais féin.

May I firstly apologise that I speak here in English, in the language of international capitalism, the language of our historical and current oppressor, in a language so wedded to plunder, dominance and annihilation that every syllable we utter in it is designed to bring us into the hegemony of our oppressor and the false consciousness that requires us to accept this oppression as natural and deserved.

In trying to understand the role of language in struggle, we need only look to our own history. If it is true that the colonisation of Ireland provided a template for colonial and imperial expansion throughout the world, it is also true to say that the history of resistance in Ireland provides a template for those who would dare conceive of a world beyond cultural, political, and economic subjugation.

The history of struggle in Ireland is both a story of physical force and cultural resistance.

Colonialism is not only a process of violent occupation, acquisition, and subjugation, but it is also a process that must be consolidated by the domination of every aspect of the lives of its victims in a way that forces the colonised to internalise their own subjugation by accepting the false narrative of colonial hegemony, rooted in notions of racial superiority of the coloniser and the consequent inferiority of the colonised.

In Ireland this process has been resisted throughout the centuries by armed resistance, rising, and liberation struggles, but crucially, often driven by, and also accompanied by, the assertion of national identity, language, culture, and counter-hegemony.

Therefore, it seems clear for colonialism to prevail it is necessary not only to physically dominate but also to create and consolidate hegemonic ideas that acquiesce to domination.

Paolo Freire asserts that colonialism only succeeds when those invaded become convinced of their own intrinsic inferiority and become alienated from the spirit of their own culture and themselves.

Thus, the early colonisation of Ireland, the Norman invasion, failed, to the extent that it was unable to penetrate Irish society beyond the Pale. The Irish language and the Gaelic way of life remained dominant in Ireland till the 1600s.

In fact, for two hundred years, feudal colonists adapted to Irish culture and practice and appeared to have “gone native”, such was the strength of Gaelic culture. This failure necessitated a deepening of the colonial project with further conquest and repression.

The 16th century signalled the birth of English nationalism, and with it, an expansionist ambition to create a vast empire throughout the world. Colonialism had honed itself militarily and ideologically sufficiently to understand that exploitation and the reaping of the material benefits of its efforts necessitated not only military but also cultural domination to project, and protect, these aspirations.

This consolidation of colonial power in Ireland, masked in the ideology of the coloniser acting as a civilising force, justified not only land confiscation and plantation, but necessitated the violent destruction of Gaelic Ireland at this time. The suppression of laws, customs and social relations brought the destruction of a trajectory of development of society that was much more egalitarian and potentially progressive than that which replaced it.

With the obliteration of the Gaelic system, it might be argued, came a distortion of history that paved the way for and made possible the eventual imposition of capitalist social relations on the society of Ireland.

The process of creating a colonial hegemony saw Irish language denied access to every vestige of state and authority and the open instigation of laws for its repression. The message was clear: to have a say in society it would not only be necessary to accept the parameters of the writ of colonial power but also its method of delivery, its language.

The impact of such policies saw the beginning of the classic colonial condition whereby the colonised language is seen to have no use or power, and the elites start to adopt and emulate the oppressor.

By the 1840s, the Catholic church for instance, as part of its absorption into the colonial realm, accepts the proviso of English being the language of its universities, and Daniel O’Connell, the so-called liberator, was able to declare: “the superior utility of the English language as a medium of modern communication is so great that I can witness without a sigh the demise of Irish.”

The systemised attack on the Irish psyche was further endorsed through a colonial school system that left Irish as non-language and thus by inference the Irish people a non-people. For example, Irish children attending school were daily forced to recite the following mantra

“I thank the goodness and the grace

Which on my birth have smiled

And made in these Christian days,

A happy English child.”

Despite this, the Irish language remained the vernacular language of over half the population of Ireland up till the time of the Great Hunger. Such was the strength of the language within Irish culture that it took a genocide to bring about the rapid decline of the 19th century.

This dramatic decline is attributed to a phenomenal abandonment by Irish speakers of their own language due to its association with poverty and hunger. Colonialism had succeeded in associating Irish with illiteracy, ignorance, poverty and all the negative stereotypes that underpinned the mass starvation of the population. The impact was such that the process of emulation and aspiration to become assimilated seemed almost complete.

Despite all this and more, the struggle for national liberation in Ireland remained strong, and in that struggle the preservation and revival of the Irish language would play a crucial part.

From as far back as 1790, from the United Irishmen to recent struggles, all revolutionary events in Ireland have either been accompanied or led by cultural resistance movements.

The United Irishmen clearly saw the preservation of the Irish language as key to breaking the link with Britain, reversing the process of colonial subjugation and fostering a progressive national identity in anticipation of a republic.

Furthermore, they saw the Irish language as a bridge between colonial-fostered sectarian divisions.

Thomas Russell wrote: “to persuade the Irish of the value of their own language is to remind them that they had a system of law before Elizabeth and James.” Edward Fitzgerald called for the English language to be abolished. This realisation of the importance of cultural resistance led further to coalitions with the remnants of Gaelic Irish peasantry and the forming of common cause not only in cultural but political aspirations.

In the middle of the 19th century, the Young Irelanders took up the project of decolonisation again with Thomas Davis’s assertion that a nation should guard its language more than its territories in the appeal for the development of a counter-hegemony to colonial domination. He declared that to lose your native tongue and to learn that of another is a chain on the soul and a greater humiliation than the loss of territory.

Later, building on Davis’s legacy, the Gaelic League set out to on a project of de-anglicisation that was designed to undo the shame of defeat, dispossession, humiliation, and impoverishment that is the classical colonial condition.

If any proof needed to be offered for the effectiveness of language movements as a radicalising force in political struggle, the very task of revival, brought the Gaelic League into coalition with the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and away from a declared position of non-involvement in national politics to understanding that language revival could not be achieved without national liberation, and that national liberation could not achieved without cultural revival. Ní amháin Gaeilge ach saor, ní amháin saor ach Gaeilge.

Furthermore, James Connolly, realising the radicalising power of cultural forces and potential historical cultural memory, set out to create a socialist counter-hegemony based on national pride and historical cultural awareness.

Connolly’s Reconquest of Ireland (1915) offered not only an alternative narrative to that of imperial rule in Ireland but, by depicting the Gaelic past as one of society based on cooperative systems, he offered the prospect of reconquest leading to a socialist future.

Connolly, recognising that colonialism had long since become a function of capitalism and morphed into imperialism, understood that decolonisation alone would not necessarily lead to political power for the working class and anticipated that colonialism could be replaced by neo-colonialism if not driven by socialist demands.

Sadly, Connolly was right about the ideological weakness of the national liberation movement. While cultural revival in Ireland might be argued to have provided a crucial reviving force in the a trajectory that led to the 1916 Rising, the Proclamation of the Republic, and the Black & Tan War beyond that, the revolutionary potential of language revival as a progressive counter-hegemony was quickly repressed and absorbed into the counter-revolution that saw the establishment of a neo-colonial conservative state in the south and the institutionalisation of reaction in the north.

From the outset of the civil war the cross-class coalition that was the Gaelic League began to split, suffering decline in its efforts and revolutionary potential, much like the revolutionary movement it had driven.

In the 26 Counties, the bourgeois state incorporated the Irish language as a symbol of its legitimacy, while at the same time overseeing the decimation of the remaining Gaeltacht areas. The Irish language fell into the ownership of the civil servants and the schoolteacher, isolating it from its revolutionary potential.

While in the North, historically language activism has continued to play a role in resistance to British rule, wedded as it is to independence and re-unification. Colonial efforts appear to be now focussed on de-politicising and containing this activism.

Language rights remain a focus of struggle as many committed activists and groups like Lasair Dhearg attempt to link the cause of labour with the cause of national liberation with language rights campaigns.

The current pacification process appears now to be using the granting of Irish language rights as a way of assuaging republicans and nationalists from associating language rights with independence, by positioning language rights firmly within the colonial sectarian construct. Thus, Irish language rights are weighed against Ulster Scots in a process of patronage and paternal accommodation, always in the gift of the imperial powers, and firmly within their sectarian constructs, separated from any aspiration to national liberation.

We have over a century of experience to draw upon when trying to understand the continued decline of Irish language and culture. That experience tells us that without language and culture linked to the radical and social, economic and political transformation of society, it has and will continue to decline. The ruling class are committed to their strategic alliance with Britain, the US and the EU, politically and culturally.

To these foreign powers, they will follow a subservient role politically and culturally. They see the assertion of a strong Irish language as an obstacle to their total integration into that imperial world.

In short, the struggle against imperialism must start in the struggle to free our own minds from the thoughts, words and constructs that the oppressor has embedded in us. Resisting the language of the oppressor is a powerful weapon in this process. The power of language resistance in struggle lies in its potential for developing a counter-narrative to that of imperialist hegemony.

But it is also true that, much like the struggle for national liberation itself, language resistance cannot deliver real political and economic power unless these struggles are grounded in a scientific understanding of imperialism as the highest form of capitalism, and a knowledge of the language of Marxism that might provide the tools to oppose it.

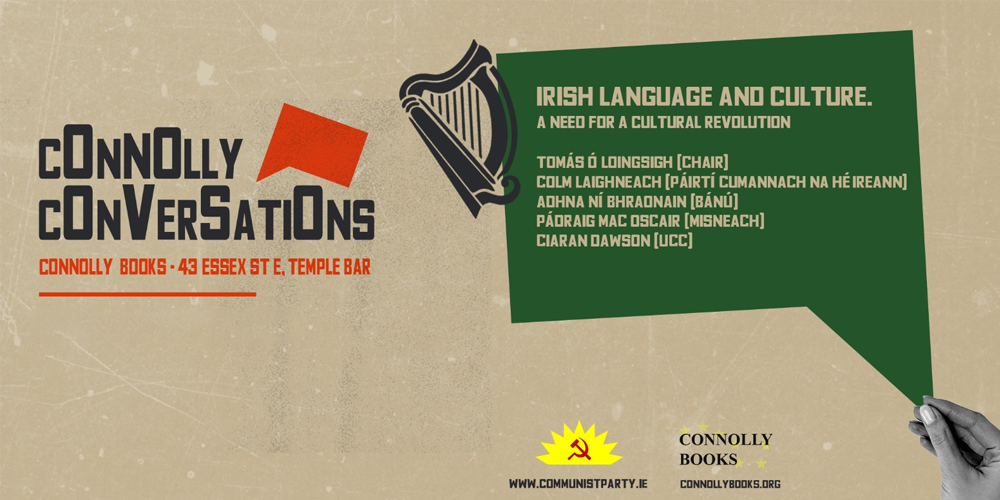

(This paper was delivered at “Irish Language & Culture – a need for a cultural revolution” talk as part of the Connolly Conversations)