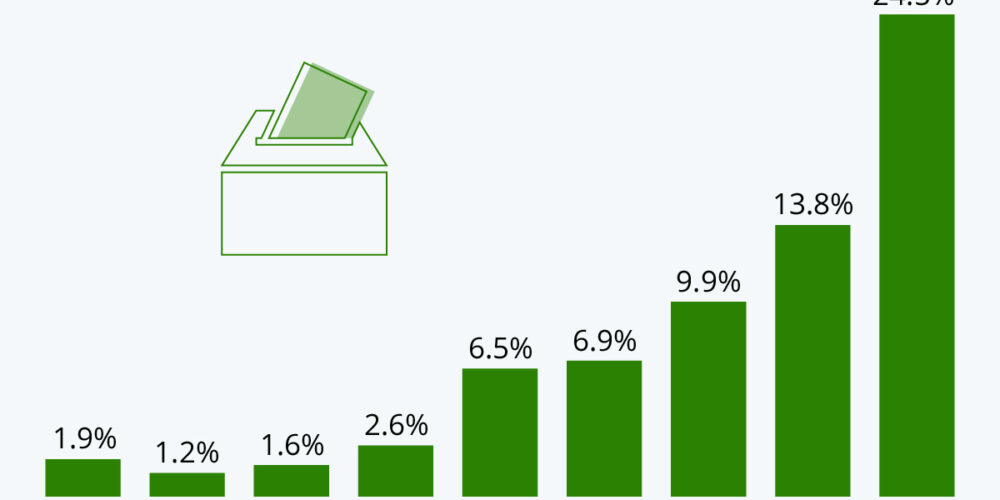

Recent articles in Socialist Voice by Comrades O’Neill, McGoldrick, and Murphy explore whether the left should support Sinn Féin in the upcoming election. While both sets of authors present persuasive arguments, the debate may be misplaced. It’s unlikely that Sinn Féin is particularly concerned with the socialist left or its “conditions”. Given that the socialist left consistently struggles to surpass 2 percent of the electoral share, coupled with occasional “holier than thou” posturing towards Sinn Féin, we might need to get our own house in order first.

More intriguingly, O’Neill, McGoldrick, and Murray express scepticism towards electoral politics. McGoldrick and Murray advocate for a path reminiscent of “Council Communism,” a theory critiqued by Lenin in Left-Wing Communism. While this isn’t a reason to dismiss their approach, and they raise many valid points, their vision of creating radical participatory democratic councils that could evolve into dual power seems challenging. Voluntary activism is already difficult; adding the task of building and sustaining new alternative institutions complicates matters further. Who, apart from the “usual suspects” and other small, marginalised groups, would participate? In Ireland, active involvement in civil society is minimal outside of the GAA. It’s also worth noting that most existing civil society organisations focus much of their energy on lobbying the government and political parties for policy and legislative change, which those so dismissive of electoralism should consider.

Despite voter turnout in Ireland being unimpressive and varying widely by time, place, and socio-economic category, electoral politics remains the primary way most people engage with the political sphere, even if only through passive consumption of spectacle and soundbites on social media. This is true for both voters and non-voters. Communists have long recognised the advantages of electoral participation. Engels noted that elections gauge support for Communist policies, provide a platform for propaganda, help connect with disengaged segments of the population, and compel other parties to defend their positions. As Engels observed, speaking in parliament carries “a different authority and freedom” compared to the press or public meetings (see Preface to Marx’s The Class Struggles in France).

Additionally, Exchequer funding is another modern benefit worth considering. No Marxist expects electoralism alone to bring about social change—significant change only occurs from outside the electoral system via crises in the productive forces, with war potentially a close second (although the latter can subsume under the former). Under normal, non-crisis conditions, Communists should fully utilise existing institutions to build working-class (and possibly petit bourgeois) confidence in preparation for times of “qualitative breaks.” Indeed, it might be remembered the Communist Party of Ireland last gained some national coverage during the 2008 crises when the leadership correctly espoused a State Bank policy: crises bring opportunities, but they need the prior groundwork to be capitalised on.

Rather than shying away from the electorate, it’s worth examining how small political parties gain influence. This almost always involves being electable at some level or, at the very least, significantly influencing those who are. Valuable research exists on how micro-Green parties in Europe moved from the fringe in the 1980s, which is worth exploring. Conversely, the struggles of People Before Profit (PBP) in Ireland, which after nearly 20 years has failed to surpass a 2% vote share, deserve study to understand how to avoid their pitfalls, despite their recent commendable local council results. The KPÖ (Communist Party of Austria) offers recent lessons, having seen modest growth in recent elections through a combination of strategic initiatives, charismatic leadership, and modernising their image to avoid being trapped by history and dogma.

Electoralism will never deliver “the transformative strategy.” It presents substantial contradictions and there is already an electoral squeeze within the relevant space. However, under normal conditions, the left must endure a long march through existing institutions. By being politically present within mainstream institutions when a crisis inevitably occurs, one stands a chance to capitalise on those moments when decades happen, and break from those decades where nothing happens.