On 13 July, An Taisce hosted Kevin Anderson’s talk “A Velvet or Violent Climate Revolution: Which Will We Choose?” in the Tailors’ Hall, Dublin. Anderson was introduced as a climate scientist “telling it as it is”—a tagline reinforced by his opening slide, in which he warned the audience that his presentation is not for the faint of heart. It is “red-pilled,” Anderson explained, using a reference to The Matrix; he would not hold back, no matter how uncomfortable the truth was.

Anderson made it clear that his presentation was aimed at those who already acknowledged the human-made climate change, and that it would reveal how governments and corporations are not doing enough to address it. He did so—with no mentions of the word “capitalism” and no understanding of the concept of revolution.

This curious approach, certainly tailored to the audience in the Tailors’ Hall, could not maintain a coherent flow throughout the ninety minutes of the talk and Q&A.

Throughout the presentation Anderson correctly observed that the climate emergency is not to be observed disentangled from housing, public health and labour issues. He also recognises the rampant inequality in the ownership of the means of production and pollution; he calls for “moving resources and labour from the private luxury of a relative few to public wellbeing for all.” If the top 10 per cent, he explained, cut their emissions to the EU mean, and the rest did nothing, that alone would produce a cut of one third in global CO₂.

Those who set the green agenda, as Anderson put it, are in the top 1 per cent of emitters, “or clamouring to get there”: the politicians, the academics, the financiers, the CEOs . . . and the list goes on. They, naturally, prefer to maintain the status quo, refuse conversations about a redistribution of power, and look for an economic repackaging of the crisis in the form of carbon taxes, offsetting, and technological products.

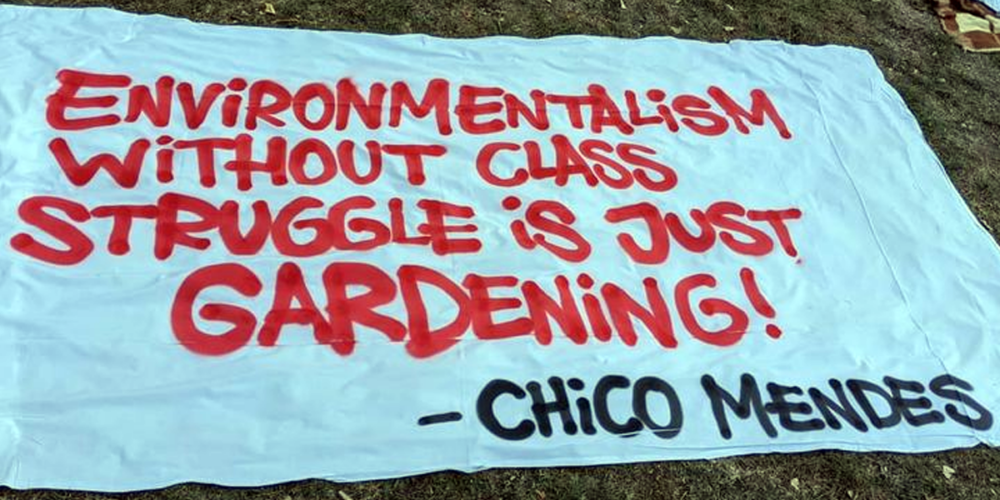

The analysis so far maps important components, but it does not really ask the question why they are connected, and it most certainly does not mention the word “capitalism.” In failing to do so it sets the stage for never touching the production relations and not recognising the class struggle anywhere beyond “poor” and “rich” individuals or countries.

Where does that take us in the alternative futures in Anderson’s view?

“It’s too late for non-radical futures,” Anderson spelt out, recognising how excited his audience is for “radical” and “progressive” as alternative to the status quo would be, at least verbally. The choice, he continued, is between a “velvet revolution” of a “deep, rapid, fair and organised decarbonisation of modern society” and “a violent revolution” with “ongoing lies, rhetoric and delay as temperatures rise.”

He acknowledged that some consider revolution a dirty word, and invited the audience to replace it with a word of their choice. Evoking the image of the Czechoslovak “velvet revolution,” Anderson proceeded with it as the preferred outcome to the violent revolution scenario (which was not elaborated at all but rather left as “anything could happen”).

This is where the slides of the presentation feature Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Michael D. Higgins, with a call for “Rooseveltian leadership for the 21st century” and “a new Marshall Plan.” Presumably this is the vision of the velvet revolution and the revolutionary leaders unrolling the large co-ordinated plan of addressing the climate crisis.

How does this happen? What does the Rooseveltian Michael D. Higgins do to convert the present state of affairs into the “velvet revolution” vision? It remains very much unclear. What sort of an economic change in ownership and management happens also remains unclear.

The lack of clarity was mirrored in the question-and-answers session that followed, with the added element of the audience looking for their agency. What is the role of activists in the velvet revolution, how are the industrial lobbies to be countered, and what can be learnt for organising in the series of Irish referendums on marriage, abortion, etc.? What is the role of social media, and what about degrowth? When is the climate emergency going to become really dangerous (sic!) for us?

When answering these, Anderson was conscious of the existing liberal bias; he warned that social media activism is not enough, and that “when is it going to affect us?” is a question with very little sense, which only serves the purpose of revealing how relative is the meaning of “we” or “us.” When asked about degrowth, Anderson pointed out that basing the economy on something other than such metrics as GDP was crucial for the future, but yet again he failed to label capitalism, or its alternative (or alternatives). When speaking about climate activism of Just Stop Oil and similar organisations, Anderson admitted that he changed his opinion gradually: from being somewhat against it to recognising its role and how it complements the work of others in raising the alarm.

While some credit can be given to Anderson for going this far with the audience he attracted to the Tailors’ Hall that evening, the vision of the “velvet revolution” very much leaves them in the dark. Even leaving aside the ahistorical romanticising of the Czechoslovak events, there is no mechanism leading to the envisaged climate future without dismantling the capitalist system. In that sense Anderson is technically and literally correct: revolution is the only future.

However, the revolution is achieved neither by the ballot for the new Roosevelt nor with activist adventurism without organising the working class. In the core of the revolution is the party; and a lot of the questions raised in the discussion after Anderson’s talk would find answers in a framework of a revolutionary party organising.