The emergence of the bourgeoisie between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries from traders, merchants and artisans marked the beginning of the modern, capitalist era, beginning in Italy. This new social class, seeking political power to underpin and further its growing economic might, found expression in the Renaissance, which displayed its confidence and its philosophical and artistic as well as scientific achievements.

The Reformation, originating in Germany in 1517, represented religious emancipation from strict feudal hierarchies. The Reformation weakened Catholicism throughout Europe. During the period 1555–1648 the Counter-Reformation took place, characterised by Catholicism’s political and military actions to thwart the effects of the Reformation, not only in central Europe.

In Europe the Baroque developed in tandem with the Counter-Reformation, glorifying the absolute power and outward splendour of the ruling class, while realist works of art reflected democratic tendencies.

In art, Caravaggio blazed the trail of realism, greatly influencing many painters. Among these was Orazio Gentileschi, father of Artemisia, who also stood firmly in the realistic tradition of Caravaggio.

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome on 8 July 1593. Her first masterpiece was Susanna and the Elders (1610), after the Biblical story. It was painted in Rome when she was only seventeen. It is a close-up composition, focusing on the figure of Susanna. She is seated on a stone bench, vulnerable, all but nude. Her whiteness, her innocence, is emphasised and contrasts sharply with the fully clothed, leering men, who have crept up behind her. Susanna’s upper body is twisted away from them in shock, her fearful face turned as far away from them as possible. Her distress is accentuated by the desperate yearning of her hands to push the men away as their hands perilously encroach upon her.

While Susanna is alone, the men form a treacherous unit, one man’s arm around the other, whispering, the second man holding his index finger vertically to his lips to seal the pact of silence.

Artemisia uses chiaroscuro to deepen the dramatic effect of her narrative. Natural light shines on Susanna’s torso and the sheet, which are the men’s central interest. This colouring, along with the massive weight pushing down from the sinister predators, intensifies the emotional atmosphere and highlights Susanna’s isolation and vulnerability.

Another popular Biblical subject Artemisia turned to was that of Judith slaying Holofernes, from the Book of Judith. Artemisia painted Judith Slaying Holofernes twice. The second painting (1620) has gained in realism. Artemisia assigns both women an active role: the maid holds down the powerful man while Judith performs the actual killing. Artemisia presents a young woman, whose full bodily weight and strength is required to pin down Holofernes. An incredible force emanates from Judith.

The power, energy and sheer strength of these two women in action is almost peerless in the history of art. They have come to do a job; we witness them doing it, at the height of the action. Their fully extended arms push down on the general with great force. True to the Bible, Judith is dressed in her finest clothes (she needed to impress Holofernes), down to the bracelet—which, according to some experts, depicts Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and of chastity.

The women are splattered with blood; Holofernes’ blood spurts from his neck onto the bed and the women. Their faces capture the intensity of the moment. The composition, with the sword at its centre, creates a sense of immediacy and emphasises Judith’s determination.

Finally, let’s look at Artemisia’s self-portrait as The Allegory of Painting (1638–39), painted in London while she stayed with her father, when she was in her mid-forties.

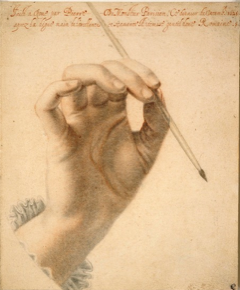

This picture is both allegory and self-portrait. Unusually for a self-portrait, the artist does not look at the viewer. She is completely focused on her creative activity, shown in a most unusual perspective—one that required two angled mirrors to allow observation of this posture. The painter is positioned to the side of the canvas, with a diagonal running from top left to bottom right of the picture, along her painting right arm and her chest. This off-centre positioning creates a singularly dynamic and unconventional composition.

The sleeve of the right arm is rolled up; she is wearing a brown apron over her dress: she is working. In her right hand she holds the brush that is about to touch the canvas. In her left hand the artist-subject holds the rectangular palette, resting on a simple support. In keeping with the intense concentration on her work, the painting is bare of any detail.

Artemisia is both the subject and the object of the picture. Gravity causes a pendant to hang away from the angled body, thereby attracting attention. The pendant represents a mask, saying that what we are shown in art is only the image of something, not the actual thing.

The entire focus is on the person of Artemisia. In the background there is a vertical line, separating two brown tones. The lighter shade probably signifies the grounding of the canvas before the imminent application of other paints by the artist. As we witness the artist touching the surface we behold the moment of creation. Both canvas and wall are bare, suggesting that the painting is not finished but in the process of creation. This is the allegory of painting at work. It is an amazing work of art.

As one of the great disciples of Caravaggio, and although well known, Artemisia received no public commissions while resident in Rome, Florence, or Venice, as her realism must have been seen in conflict with the Baroque ideals. Naples was more open to it, and it was here that she spent the last twenty years of her life and that she died, possibly during the plague of 1656. All but forgotten for centuries, her realist art was rediscovered and celebrated in the twentieth century.