Last month’s local government election results were even more significant than simply the storming performance by Sinn Féin. The outcome has underlined an inexorable direction of travel that points to the decline not just of unionist political hegemony, but of the very union itself. Not only is unionism losing out in the crucial numbers game but is also witnessing the economic failing of the Six Counties.

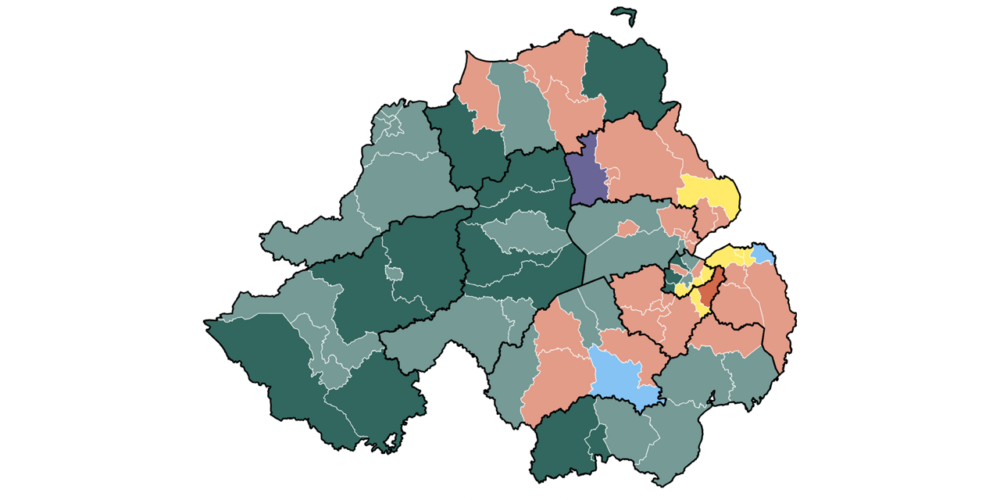

The DUP vote actually held up, yet in spite of that Sinn Féin still won more seats. Even more ominous for avowed supporters of the English connection was the realisation that overall they are in a minority across local government in the North. Councillors elected who publicly favour ending partition have a small numerical advantage over those committed to its maintenance. When the constitutionally agnostic such as Alliance is also taken into consideration, those identifying purely as unionist are left in a minority of slightly over 40% across all eleven council districts.

Coming as this does on the heels of the disconcerting sight of Sinn Fein’s Michelle O’Neill claiming the First Minister’s title (if not office) coupled with the unnerving demographic shift recorded in the latest census toll, the evidence of fundamental change is clear to all but the most myopic.

That this fact is certainly recognised by hard-headed observers of northern life became apparent recently when BBC in Belfast recorded a series of podcasts in the run-up to the local government elections. One episode dealing with the challenges facing unionism in general was addressed by two well-known local political commentators, BBC reporter Gareth Gordon and Sam McBride, Northern Ireland editor of the Belfast Telegraph and Sunday Independent. Both participants are outstanding journalists but by no stretch of the imagination can they be described as carrying a banner for Irish republicanism.

Their assessment of the situation was stark: unionism is in decline and apparently incapable of reversing the trend. Coming as it did from two people with no obvious reason to undermine the North’s position within the UK, this is telling. Moreover, election day results bore out their analysis, lending weight to the view that the current status quo is not permanently sustainable.

Nor indeed is the latest political upset the only factor auguring against the long-term future of the partitioned statelet. Where once Belfast’s wealthy bourgeoisie enjoyed a place at the forefront of the British Empire’s manufacturing elite, that day has long gone. No longer is it possible to advocate the unionist case by pointing to the economic advantages of being embedded within the Empire’s captured territory. The Empire is no more, Britain’s economy is faltering and the North is the weakest and poorest region of the UK.

Worse still from a unionist perspective is the depressing fact that productivity in the Republic is on average 40% greater than that of the North. A recent report by the ESRI to an Oireachtas committee recorded this fact, along with the finding that the Six Counties lag behind the South in important aspects such as a shorter average life expectancy, lower average household income and greater levels of poverty.

None of which diminishes in any way the obscenity of inequality in the Republic, nor should there be any tolerance of that fact. Nevertheless, productivity is a key measure of a society’s wealth-generating capacity and while not overlooking how income in the 26 Counties is so ill-distributed, this means the North has lost what it long said was practically its very raison d’être.

Stalled in the trough of economic decline and political stalemate, the prospects for unionism and the union have never been bleaker. Caught up also is the hapless DUP, the leading party of unionism. Unable to manoeuvre in any positive direction that might help “make Northern Ireland viable”, the venerable Sir Jeffrey Donaldaon is leading Ireland’s unionism and the union to where it is best placed …in the dustbin of history.