An assessment of how Denmark’s three left-wing parties—the Red-Green Alliance (Enhedslisten), founded in 1989, the Alternative (Alternativet), founded in 2013, and the Independent Greens (Frie Gronne), founded in 2020—fared in the election of 1 November 2022.

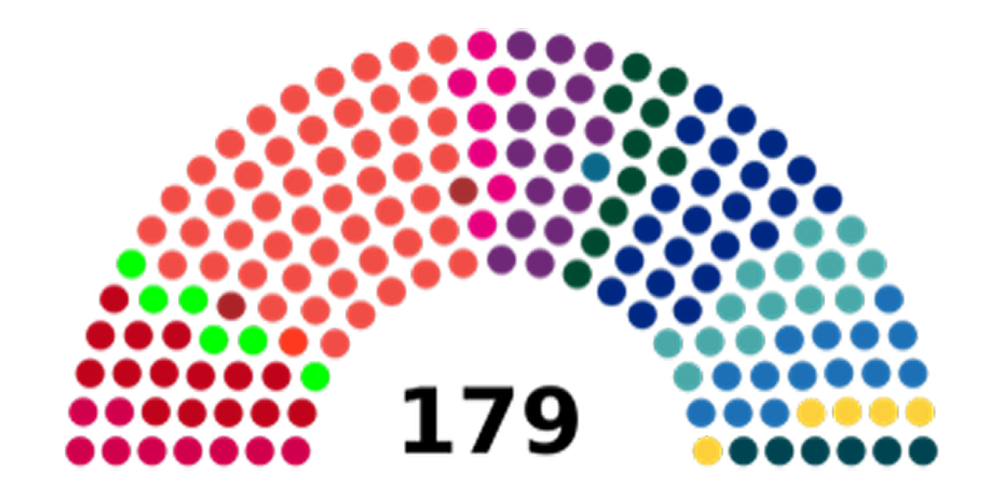

In brief: The Red-Green Alliance¹ lost four mandates, winning 9 seats; the Alternative² gained 1 mandate, winning 6 seats; while the Independent Greens³ failed to win the minimum number of votes required to gain a seat in the Danish parliament (Folketinget), and are therefore out, for now.

The stated aim of the largest left-wing party in the Folketing, the Red-Green Alliance, is to be a locally anchored workers’ party, though most of its support is centred in major urban areas. The party lost ground in all constituencies this time round, receiving only 5.2 per cent of the poll, a decline of 1.7 percentage points. It now has only nine seats in parliament, a loss of four. Its losses in its traditional stronghold, Copenhagen, came as a surprise, while it has failed consistently to gain a foothold in the provinces.

Having had so much progressive influence on government policy over the past three to four years, as an ally of the Social Democratic government, the question being posed here is, Why has the Red-Green Alliance regressed to such a degree?

The party’s chief strategist, Pelle Dragsted, believes that the Red-Green Alliance has done its utmost to bring class politics into this election campaign, concentrating, as it inevitably does, on the redistribution of wealth and equal pay, though he admits that it can always be brought up for discussion whether enough emphasis was brought to bear on class issues.

The Red-Green Alliance’s poorer-than-expected performance he blames in part on the Social Democrats usurping his party’s more radical issues. “During the campaign,” he said to Arbejderen (The Worker) on the 3rd of November, “we saw the Social Democrats appropriating several of our key issues, for example equal pay, increased pay for public sector workers, a cost ceiling on rented accommodation, and climate change action. This meant that several otherwise disgruntled social democratic voters ended up voting for them anyway.”

Like others on the left, he believe that many voted tactically to ensure that the Alternative would get in. He does not believe, however, that voters “punished“ the Red-Green Alliance for changing its position on NATO and the EU, or for supporting continuing parliamentary initiatives for sending military aid to Ukraine. Many on the left disagree strongly with his analysis here.

“The world changed very quickly when Russia attacked Ukraine,” says Dragsted. “We had to face the issue of whether we were still in favour of withdrawing from NATO. This led to a crisis within the Red-Green Alliance. Finally, we announced that a withdrawal from NATO would not be appropriate at this time. Some of our voter groups may be against NATO, but I find it difficult to see an alternative to NATO in the current security policy climate.”

However, it is not just opposition to NATO on which the Red-Green Alliance has changed its position. The same applies to its EU policy. In May 2022 it adopted a new EU programme, which dilutes its demand for Denmark’s withdrawal, to concentrate instead on support for polices designed to make the EU red and green.

Gains for the other left-wing parties

While the Red-Green Alliance lost votes in its main base, Copenhagen, the Alternative advanced three percentage points there since the last election, and the Independent Greens gained 2.2 per cent in the capital. This would indicate a move away from the Red-Green Alliance towards the other two left-wing parties.

The Independent Greens, running for the first time, are proud of their result, though they did not reach the threshold demanded to gain seats in the Folketing. “This is our first election . . . and we did succeed in mobilising voters in outlying [i.e. working-class] residential districts. Therefore this is not the end for the Independent Greens but the beginning. Everyone remembers how long it took the Red-Green Alliance to establish itself. So we are in high spirits . . .” So said the party’s leader, Sikandar Siddique, to Arbejderen on 3 November 2022.

31,000 voters chose to vote for a party that went to the polls with some relatively far-reaching campaign proposals, such as reintroducing the wealth tax and redistributing state finances to the poorest in society. The Independent Greens would also introduce a 25-hour working week, do away with parts of private property rights, and nationalise all land.

A large proportion of the Independent Greens’ potential voters are not Danish citizens, and therefore not entitled to vote. According to Statistics Denmark, there are almost 500,000 such foreign citizens in the country.

Winning 3.3 per cent of the poll, the Alternative gained an extra seat in parliament—increasing from five to six. “We succeeded in campaigning the climate into the election and bringing together several small green parties—the Vegan Party and the Green Party,” says Torsten Gejl, MP for the Alternative, to Arbejderen.

There are considerable regional differences in where the Alternative gets its votes. The party enjoys sizable support in the cities, such as Copenhagen, Aarhus, Aalborg, and Skanderborg, where progressively minded people live. But, unlike the Red-Green Alliance, it appeals as well to people in rural areas, particularly those involved in organic and alternative methods of agriculture.

Where to now?

All three parties on the left—all of which were allies of the outgoing Social Democratic government—hope that the Social Democrats will go ahead and form the red-green government for which it has a clear mandate, instead of going ahead with its coalition-across-the-aisles plans. The Red-Green Alliance has already accused the Social Democrats of “breach of promise” for continuing to discuss the basis of the new government with right-wing parties, fearing that the gains made by the last government on welfare, workers’ rights and climate action will be threatened by any alliance with the Liberals and Conservatives.

References:

■ Sources for this article include the Danish left-wing magazine Arbejderen, the weekly Weekendavisen, and the various web sites of the parties involved.

1. The Red-Green Alliance was founded in 1989 with the merger of three Marxist parties: the Communist Party of Denmark (DKP), Left Socialists (VS), and the Socialist Workers’ Party (SAP). Until 2011 the Red-Green Alliance experienced only limited success in parliamentary elections, and support from voters fluctuated. In the 1990 general election the party, polling only 1.7 per cent, failed to reach the threshold needed to gain a parliamentary seat. In the 1994 general election it won 6 seats. In both 1998 and 2001 the party lost a mandate. In 2005 it once again won 6 seats but lost two of them in the 2007 election. In 2011, helped by media attention, it increased the number of its MPs from 4 to 12, polling highest in working-class areas. By the general election of 2015 the Red-Green Alliance was the largest party in the Nørrebro and Vesterbro districts of Copenhagen. Nationally the party gained 2 seats, winning 14. In the 2019 general election the party lost one seat, winning 13. And now, in 2022, it has won only 9 seats in the Folketing. The membership of the Red-Green Alliance in 2022 is 9,662.

2. The Alternative first entered parliament after the 2015 general election, storming in with nine seats. However, in the June 2019 election the party lost four of these seats. Shortly after this election setback its then leader, Uffe Elbæk, together with two other Alternative MPs, resigned to found the Independent Greens.

3. The Independent Greens were founded in 2020 and until the 2022 general election had two members of parliament, Sikandar Siddique and Susanne Zimmer, both of whom were elected in 2019 when they were members for the Alternative.