The production process of computer games hides the built-in exploitation of both workers and customers

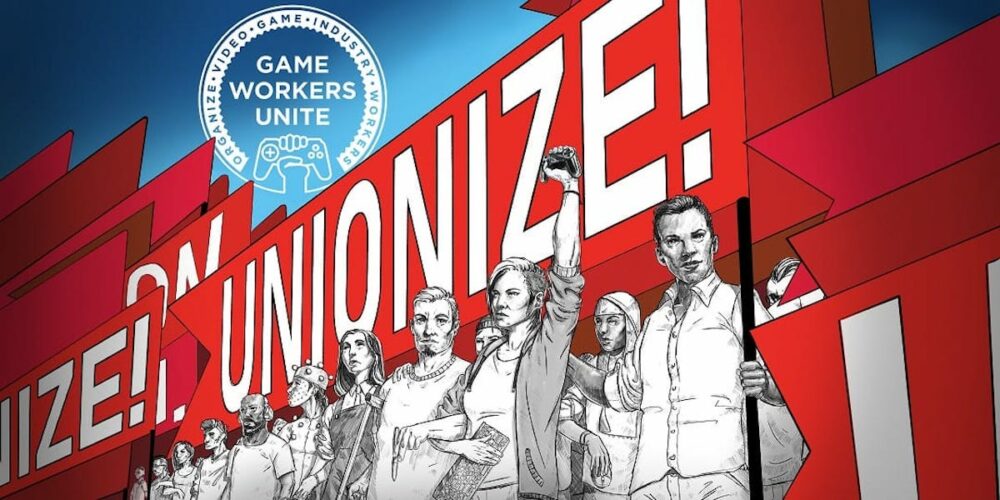

Games workers in Ireland and all over the world have begun unionising. First of all they established their own Game Workers Unite, a loose movement of workers internationally; this has since developed in a number of countries into specific, focused union organising campaigns, with such unions as the FSU in Ireland, IWGB and Prospect in Britain, Unionen in Sweden, and the CWA in North America.

Working in games is not always as much fun as it sounds. There have been a number of exposés of the games industry that identify unpaid overtime, long working hours, “crunch hours” at the end of a project, work-related stress, muscular disorders, lack of pay transparency, lack of paid sickness leave, lack of recognition in credits, non-disclosure agreements, non-compete clauses and job insecurity as prevalent and common for workers who operate in a largely non-union international production chain.

Individual workers often “resist” or react to these conditions by leaving their job, through leaking information to the media, or through “Easter eggs” (inserting a unique piece of code to stamp a game).

There were a number of prominent legal actions throughout the 1990s (for example the EA Spouse Affair, Wives of Rockstar, and Gamewatch), and these culminated in the creation of the International Game Developers’ Association. While not a union, and with employers involved, it did provide something of a collective voice on some matters and at one point did suggest that a third of all game workers wanted to unionise.

This demand has grown among game workers, and here in Ireland these workers are now organising and unionising, with the support of the Financial Services Union. This campaign has produced two important reports on working in games that have revealed poor working conditions in Ireland similar to those reported elsewhere.

The first report, “What’s the Score?”¹ emphasised the following:

- 64 per cent of respondents have experienced low pay, while 17 per cent experienced missed payments,

- 45 per cent report working unpaid overtime,

- 56 per cent have been required to work “crunch time” (overtime, often unpaid, towards the end of a project or deadline),

- 62 per cent do not have secure employment contracts, and

- 12 per cent have experienced harassment or intimidation based on their gender, ethnicity, age, or sexuality.

In reaction to these bad working conditions, the report found that

- 65 per cent of respondents want the support of an organised community of workers, and

- 64 per cent are interested in collective bargaining to improve wage standards.

These results in favour of unionisation and collective bargaining compare favourably with the international research of the IGDA from some years ago, which suggest that the movement to unionise is growing and strengthening. And in August the workers issued a second report,² looking more specifically at pay in the sector, which found that

- 90 per cent of pay increases are not published or disclosed by employers,

- 73 per cent of pay ranges are not published or disclosed by employers,

- 42 per cent do not receive an annual pay increase,

- only 15 per cent are paid for overtime,

- 78 per cent do not receive employers’ contributions to a pension scheme, and

- 15 per cent are earning less than the living wage (€12.30 per hour at the time, since increased to €12.90).

These pay conditions are frightening for any workers used to a unionised environment; but, unfortunately for non-unionised private-sector workers, pay secrecy, low pay and unpaid overtime are all too common an experience.

Yet game companies, not satisfied with only exploiting the labour of workers, also exploit the labour of gamers themselves. Gamers are often encouraged, sometimes even provided with tools or competitions, to modify and enhance games deliberately after they are launched to improve and prolong the life of the product. This “plabour,” as it has been called, is in effect the commodification of gamers’ leisure time, with the value extracted and absorbed by the owners of the game.

The production of a game can take between six months and two years and involve up to a hundred workers, organised in teams, sometimes in a variety of companies or self-employed. Designers create the vision, artists create the artwork, programmers produce the code, and producers oversee production. There are also testers and quality-assurance workers.

Publishers are top of the hierarchy of production. They finance and control the publication of games. No surprise to readers of Socialist Voice that there are not many controlling publishers! It’s suggested that there are ten firms that largely control production, and these include such names as Sony, Microsoft, EA, and Nintendo, with a regional split among the top ten of four in Japan, four in the United States, and two in China. Of the middle-sized firms there are a further six American companies, five Japanese, and a number spread throughout Europe.

To those who have read Samir Amin this triad will be familiar. The games sector globally is now the biggest, in global market worth, in the entertainment industry, with ten times the income of films and three times that of music. Within games, mobile have now passed out console or PC-based games.

It is these dominant publishers who often set what is described as the iron triangle of on budget, on time, and in scope. These are the strict boundaries of production of games. Costs and risks are often passed down the line, with the greatest profit margins taken by the top companies, and this has a massive deteriorating effect on working conditions and on workers’ health.

It is also clear that “crunch time” at the end of a project is in fact a significant and deliberate part of the production process, designed to use more free labour in addition to that already extracted through the wage-labour process.

This is the global production process of computer games, and it is a very welcome development that the workers are beginning to unionise to rebalance power in the production process.

Solidarity and support for game workers!

■ If you’re working in games, or for more information, see the GWU site at https://gwuireland.org/.

- Joshua Moody and Aphra Kerr, “What’s the Score? Surveying Game Workers in Ireland, 2020” (tinyurl.com/ytt7adf8).

- Game Workers Unite, Ireland, “Pay Transparency Report,” 2021 (tinyurl.com/b47bhdym).