As we move out of the period of pandemic, we would all like to establish some form of normality in our lives. But one thing is certain: workers must resist any return to the pre-covid “normal.” That was an economy based on low pay, with precarious employment, precarious shelter, a precarious health service, and an education system overcrowded and underfunded.

Many young workers may have received more under the pandemic emergency payment than they received working long hours and experiencing poor working conditions. What the pandemic exposed was the scale and extent of low pay and the extensive abuse of young workers and migrant workers.

The centrepiece of the anti-worker laws is the Industrial Relations Act (1990).

For young workers up to the age of thirty, the ratio of average hourly earnings to average earnings in Ireland is the second-lowest in Europe; and since 2006 this gap has widened more in Ireland than in any other of eleven high-income EU countries. In 2006 the average Irish full-time worker under thirty earned 72 per cent of the average; in 2018 it was 65 per cent.

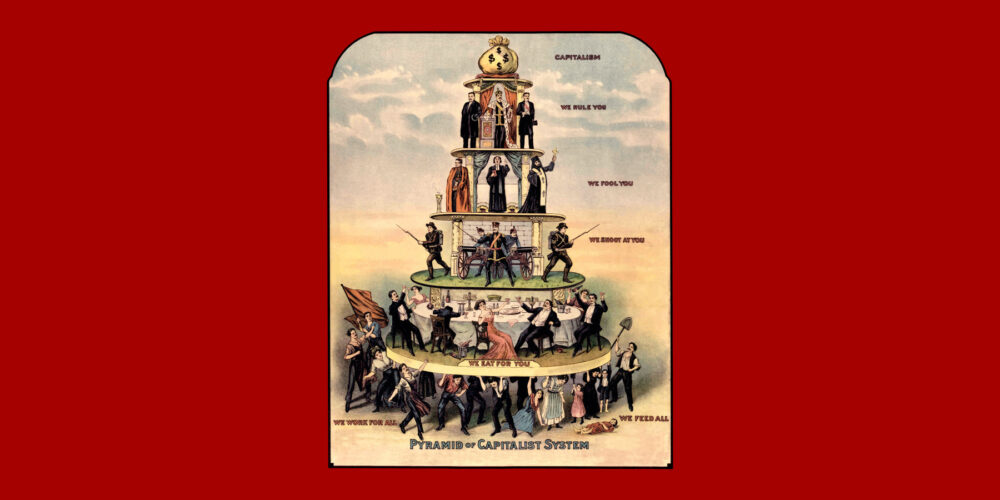

What this means simply is that the rate of exploitation of young workers is intensifying.

Much of this is due to low trade union density, combined with the difficulties experienced by unions in gaining access to work-places and extremely restrictive workers’ rights. Only 33 per cent of Irish employees are covered by a collective agreement, compared with 90 per cent in Sweden and 99 per cent in France.

This growing intergenerational inequality applies across the board, including those associated with amount of education or training and level of wages. Having a third-level education does not save you from super-exploitation. The proportion of younger workers with third-level qualifications continues to grow. Wage levels that young graduates might hope to achieve having secured a third-level education have not lived up to their aspirations.

This exposes the establishment economic narrative that you will be well rewarded for your study. It reveals the illusions peddled by establishment economists and media pundits.

As a recent article by the Nevin Economic Research Institute put it,

“Ireland has a relatively high share of workers in low pay (up to 2/3’s of the median), of young workers in low pay and is an outright outlier in the share of tertiary graduates working in jobs with low pay (13.0 per cent). Estonia is the only other country in double digits out of 30 in the entire sample and the share of Irish workers with high levels of education in low wage jobs is 8–9 times the rate in Finland and Sweden (1.5 per cent).”

The policy of the current and previous governments has clearly discriminated against workers, driving down wages and creating more precarious employment, which benefits employers, large and small, the impact of “austerity,” and the deliberate strategy of wage suppression.

When you have no control over your currency, the levers are limited.

Since 2007, all the various combinations of parties that formed governments in this state, both Fianna Fail plus Green and Fine Gael plus Labour governments, targeted younger workers, which has been a central policy plank of earnings inequality in Ireland. This will not change under the current two-party coalition government.

Research shows that where trade union organisation is weak or non-existent, wage levels are much lower than in sectors that are well organised and where trade unions are strong. Higher levels of collective bargaining lead to lower levels of inequality throughout the system. That is why the present and previous governments have shackled workers and trade unions.

There can be no return to employers’ normal. Instead the pandemic has shown that workers need to be better organised, and that trade unions need to step up their activities among the unorganised. This requires spending resources in serious organising and not just “servicing” workers.

It is in the trade union movement’s own self-interests to do this. It also needs to take more seriously the necessity to campaign for the repeal of the 1990 act and its replacement with legislation that guarantees workers’ rights, including the right to join and be represented by a union. Workers, in particular low-paid workers, need a pay increase to bring the minimum wage up to €15 per hour.