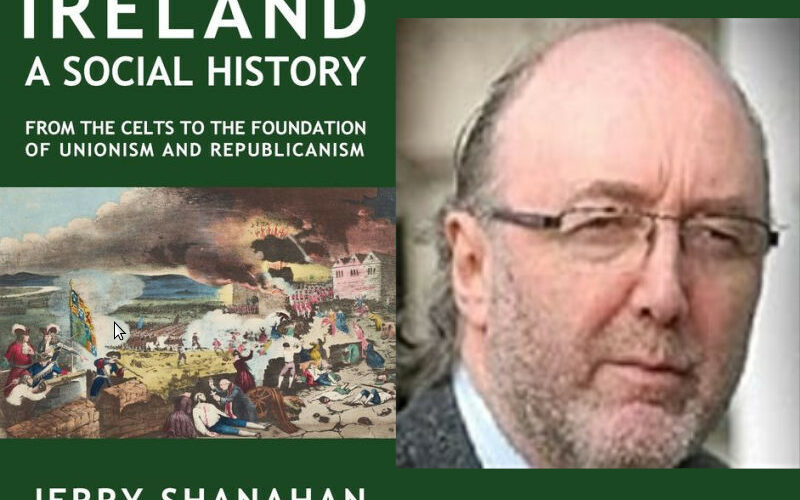

■ Jerry Shanahan, Ireland: A Social History (Dublin, 2021)

Much left-wing literature in the twenty-first century seems to suggest that history began in 1848 or, at the earliest, in 1789. This unmarxist view tends towards a blinkered understanding of the roots of modern society and the development of capitalism and imperialism. Therefore, this work by Jerry Shanahan, subtitled From the Celts to the Foundation of Unionism and Republicanism, is to be welcomed.

He challenges the dominant approach of Irish professional historians in the twentieth century who followed the pre-eminent English history institutes in pursuing a “value-free” interpretation of history. These bodies held a view that the Empire was something benign, a view we still get in television programmes and in Ireland from their Irish trainees and disciples: the notion that colonisation and occupation wasn’t all that bad.

Shanahan also challenges the mindset that fails to recognise the struggle for national independence as part of the democratic process. He draws from the work of Connolly and Tommy Jackson but adds to them and does not follow them mechanically.

One of the characteristics of this work is that the author finds it necessary to take into account events and processes elsewhere in Europe and particularly in Scotland, Wales, and England. This is especially enlightening in the traumas of the seventeenth century. The plantations, especially that of six counties of Ulster (not that Six!) were designed to drive out the native Irish and were not entirely successful but formed a template for future genocidal projects in the burgeoning empire. The aim was to deprive the indigenous population of the means of sustenance and reduce them to becoming a marginal under-class, and then to “civilise” whatever of them were left.

It was in that period that religion was introduced into the colonial project as a political identifier. The counter-revolutionary Cromwell was able to call upon God in his campaign of genocide in Ireland. A mass cohort of new colonists were “granted” most of the land of Ireland and formed the new controlling ascendancy.

What was left of “Old English” and the few remaining Gaelic landholders lost their estates after the Williamite War, part of a European conflict between Louis XIV of France and his allies on one side and a coalition including William of Orange and Pope Innocent XI on the other. William’s victory at the Battle of the Boyne was celebrated by high masses in Rome, Vienna, Madrid, and Brussels.

The eighteenth century saw a minority of cosseted landowners estranged from and lording over the vast majority living in terrible poverty. It also saw the growth of a native middle class, which grew to become a major economic and political force. This was the class that produced O’Connellism and Redmondism and eventually led the counter-revolution of 1922—but that is beyond the scope of the current work.

Shanahan gives a good concise account of the emergence of republicanism in Ireland in the 1790s and the inevitable reaction to it in the form of Orangeism, cultivated and promoted by Dublin Castle. The early 1790s saw a virtual civil war in the Armagh area, where loyalist gangs were carrying out ethnic cleansing of large parts. The so-called Battle of the Diamond was followed by the establishment of the Orange Order.

The author aptly quotes Jemmy Hope, who at the time pointed out that land greed was “the real basis for the persecution in the County Armagh, religious profession being only a pretext, to banish a Roman Catholic from his snug little cottage or spot of land and get possessed of it.” Dublin Castle provided huge sums of money to the new Orange Order and promoted it on a national level, and it had the enthusiastic support of the hideous Lord Castlereagh. Thus was implanted one of the causes of partition.

The scope of Jerry Shanahan’s work will, no doubt, leave him open to nit-picking by historians, amateur and professional. Its purpose is to illuminate the major processes in Irish history from the Middle Ages to the beginning of the nineteenth century, with appropriate recognition of the social aspect. On the whole he has succeeded and deserves a wide readership.