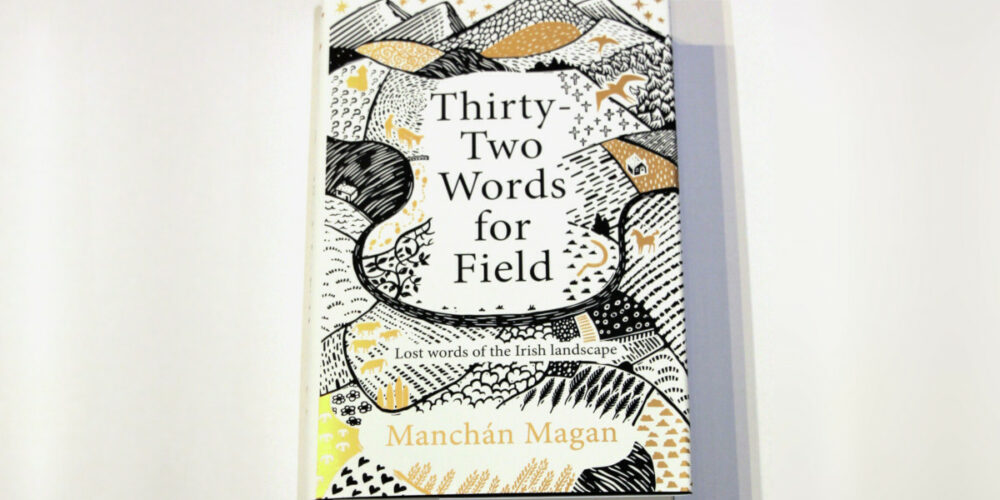

Manchán Magan, Thirty-Two Words for Field (Dublin: Gill Books, 2020).

This acclaimed book ostensibly celebrates the Irish-speaking community in Co. Kerry, where the author spent his holidays as a young man.

He explores the rich vocabulary of traditional Irish-speakers and their words for natural phenomena: the weather, the sea, plants, animals—and fields. But it’s all presented as an oddity, a peculiarity, something to be marvelled at as a kind of aberration, and even a source of amusement. His readers, mostly no doubt monoglot English-speakers, are presented with a dizzying array of vocabulary, sometimes differentiated but more often as a mere list, as if all the words were synonymous. This is inevitably contrasted, at least by implication, with English, the language of precision, reason, and civilisation.

The Irish Times described the book as “a rip-roaring archaeological exploration of the lyricism, mystery and oddities of the Irish language.” But the Irish-speaking community are not lacking in recognition for their “lyricism” or oddities but rather for their civil rights.

Why would any functional society present one of its languages almost as a freak show? The question answers itself: this is not a functional society but a deeply dysfunctional one, shaped by centuries of colonisation, followed by a century of self-colonisation.

It’s impossible to avoid the suspicion that the book was inspired by the notorious “fifty Eskimo words for snow,” long exposed not only as offensive but as complete nonsense; and there’s no doubt at all that this is what prompted the publishers’ choice of title.

This book, whatever the high principles of the author, is firmly in that tradition.