The 150th birthday of Rosa Luxemburg

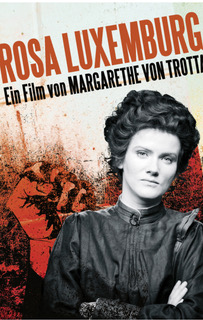

On 5 March 2021 we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Rosa Luxemburg’s birth. No-one who wishes to get a sense of Rosa Luxemburg as a person, both political and private, will regret watching Margarethe von Trotta’s meticulously researched film of the same name, made in 1968. It is available with English subtitles.

The film begins on 7 December 1916 with Rosa Luxemburg in Vronke prison, cutting back to this location again and again. Von Trotta uses Luxemburg’s prison letters to her good friend Sonja Liebknecht like a leitmotif right through the film to paint a very sensitive and personal portrait of this Polish revolutionary. From this prison the viewer relives many episodes of Rosa’s life in flashbacks. Some of these evoke the more personal aspects of Luxemburg’s life. Early childhood is touched on.

Some of these sequences are in Polish, adding greatly to the authentic feel of the film. Throughout the film Luxemburg occasionally speaks in Polish, especially to Leo Jogiches, her close comrade and lover of many years. Her letters reveal her love of nature, of animals, and her prison “garden,” for children and her close friends, creating the sense of a profoundly humane person.

Von Trotta magnificently brings together important stages in Luxemburg’s political career. The main parts of the film deal with Luxemburg’s political activity in Berlin. Considerable time is devoted to her growing disillusionment with the leadership of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). Poignantly, the SPD leader Friedrich Ebert says to Luxemburg at a dinner party that events in Russia have ultra-radicalised her and continues, in chilling foreshadowing, “We will hang you.”

From early on she senses and tackles the reformism of the SPD leadership. The complete betrayal by the social-democratic leadership becomes shockingly clear in the scene where Karl Liebknecht emerges from the Reichstag to tell her that all SPD parliamentarians had voted in favour of the granting of war funds. Liebknecht was the only member of parliament in 1914 to oppose these. National chauvinism, as a direct result of this party’s reformism, drives them into their disastrous support for the First World War.

Luxemburg unmasks time and again the profoundly inhuman nature of war as the senseless slaughter of working people in the interests of power and profits. Her anti-war struggle becomes a central theme of the film, and her speeches apply uncannily to our own times: “European problems and interests are now fought out on the world seas and in the by-corners of Europe. Hence the ‘United States of Europe’ is an idea which runs directly counter both economically and politically to the path of progress.”

Following her arrest for speaking at an anti-war rally in Berlin in 1913, she defended herself in the courtroom: “When the majority of working people realise . . . that wars are barbaric, deeply immoral, reactionary, and anti-people, then wars will have become impossible.”

Faced with the betrayal of the SPD leadership, Liebknecht, Luxemburg and Zetkin discuss the need for a new party, the Spartacus League, which went on to become the Communist Party of Germany. Luxemburg is put in “protective custody,” imprisoned from 10 July 1916, and released on 9 November 1918. During this time she is allowed books and letters and secretly passes visitors her contributions to the “Spartacus Letters.”

On the day of Luxemburg’s release the Kaiser abdicates and the SPD politician Philipp Scheidemann proclaims Germany a republic, with the SPD leader Ebert taking power. He prevents the country from turning into the soviet socialist republic that Liebknecht proclaims on the same day. The Communist Party of Germany is founded on New Year’s Day 1919. Uprisings in Berlin against the Ebert government follow in the second week of January.

Luxemburg and Liebknecht do not see eye to eye in the analysis of the rising. They are now “wanted.” They are betrayed, tracked to their hiding-place on 15 January 1919; and the rest is history.

The film does not make clear Ebert’s final betrayal of his erstwhile comrades. An officer of the General Staff, Captain Waldemar Pabst, informed the Reich government at an early stage about the arrest of the two. Pabst lived until 1970 in West Germany and in old age maintained that the SPD leadership, in the person of Gustav Noske and in all likelihood Ebert, had agreed the killings.

Expressing her profound belief in the eventual and unstoppable liberation of humankind, Luxemburg declares:

The day approaches when we who are at the bottom will rise! Not to carry out that bloody fantasy of mutiny and slaughter that hovers before the terrified eyes of the prosecutors, no, we who will rise to power will be the first to realise a social order worthy of the human race, a society that knows no exploitation of one human by another, that knows no genocide, a society that will realise the ideals of both the oldest founders of religion and the greatest philosophers of humanity. In order to bring about this new day as quickly as possible we must use our utmost powers, without looking to any success, in defiance of all public prosecutors, in defiance of all military power. Our slogan will become reality: The people are with us, victory is with us!