There has been a lot of discussion lately in left circles about the relationship between the Connolly Youth Movement and the Communist Party of Ireland, a relationship, it must be said, that is going through a difficult time at the moment. In an attempt to give some context and to clarify some historical aspects of the relationship, Socialist Voice asked Seán Edwards (CPI international convenor and a founder-member of the CYM) and Eddie Glackin (CPI education convenor and a former general secretary of the CYM) for their recollections of the formation and early years of the CYM and its relationship with the party.

The Connolly Youth Movement was established as an initiative of the then Irish Workers’ Party (now the Communist Party of Ireland) after the general election of November 1965 in the 26 Counties. Approximately seven young party members were involved in this initiative, including some who later went on to become prominent trade union leaders, such as Gerry Fleming, Mick O’Reilly, and Bernard Brown.

Others to the fore at the time were Liam Mulready, from a well-known socialist republican family, who became secretary, Irwin Hutchinson, and Seán Edwards, who was also from a prominent socialist and republican background. Seán’s parents, Frank and Bobbie, had been involved in the struggle for decades at that time, Frank having fought in the Anti-Fascist War in Spain and subsequently driven out of his teaching post in Waterford by clerical reaction, i.e. the local Catholic bishop. In his later years Frank built and led the Ireland-USSR Friendship Society along with John Swift senior.

Seán recalls (from a distance of fifty-five years!): “We had a flag, the blue starry plough with CYM inscribed on it. We paraded the flag around Dublin and gradually started to attract new members, showing ourselves as a militant youth group, and frequently picketed the US embassy. We did not describe ourselves as the youth wing of the IWP but remained very close to it. Members shared a particular respect for Michael O’Riordan, who took a great interest in our organisation.”

Eddie was one of the fairly large group of young people attracted to the CYM in the mid to late 1960s. At the time there was no other radical political youth organisation in the 26-County state, and the CYM became the outlet for the frustration of hundreds of young people, with a large membership based in the IWP premises at 37 Pembroke Lane, Ballsbridge, and subsequently active branches in Cork and, notably, in Sligo, where the leader was (now Councillor and former TD) Declan Bree. Pockets of members existed elsewhere around the country.

A bunch of us travelled down from Dublin and camped overnight for the public launch of the Sligo Branch, a large meeting that was carefully monitored by a branch of another type: the Special Branch. Police and Special Branch harassment was a daily feature of life for CYM-ers in those days: phones were tapped (but not every home had a phone in the 60s), mail was opened, nasty calls were made to parents, employers were visited, some members were followed home from CYM meetings by not-so-subtle Special Branch men—all in an attempt to put young people off being involved.

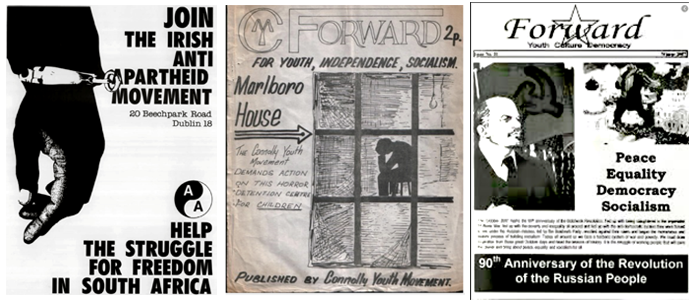

The Dublin members met every Wednesday in Pembroke Lane. The main emphasis was on educational activities, but there was also a fairly frantic level of activity involved in writing, typing and printing our paper, Change (later Forward). Typing was usually done on an old-fashioned typewriter onto paper stencils, which were then wrapped round the inked drum of a stencil duplicator and run off by hand.

An even messier process was the production of posters. We designed and printed our own posters—lots of them—by the silkscreen process, and the floor of the upstairs meeting-room in Pembroke Lane was regularly covered with drying posters.

In the early years, before members became actively involved in trade union and broader organisations, the emphasis was on propaganda, especially posters and leaflets. Dublin was regularly plastered with CYM recruiting posters and others dealing with issues of particular concern to young people, such as emigration, youth unemployment, campaigning for the closure of “reform schools,” education problems, school pupils’ and apprentices’ rights, etc. We also had a weekly bookstall every Saturday at the GPO—the first to claim that spot—a practice that was followed in Cork and in Sligo.

A huge issue for us was the American war in Vietnam. In fact Eddie’s first contact with the CYM came when he joined an early CYM picket on the US embassy one Saturday morning. The CYM was actively involved in an organisation called the Irish Voice on Vietnam, which was headed by such great fighters as Peadar O’Donnell. It organised large demonstrations at which CYM members, because of our discipline, were frequently asked to act as stewards.

Other issues in the late 1960s were solidarity with the youth and people of Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), opposition to the British role in Aden (now part of Yemen), and many other international campaigns.

But perhaps the most important international cause, alongside Vietnam, was the world campaign against Apartheid South Africa. This was given very high priority. Both Seán and Eddie served on the Executive Committee of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement, Seán in his own right and Eddie as CYM representative. Seán at one point was sent into South Africa incognito on a dangerous mission to distribute leaflets on behalf of the banned African National Congress, a mission that he accomplished and, most importantly, returned safely from!

The CYM members were privileged to play an active role over the years in the IAAM, which was held up by Oliver Tambo, acting president of the ANC during the incarceration of Nelson Mandela, as the best of the international solidarity movements. We were also privileged to meet such great leaders as Tambo and Amilcar Cabral, leader of the PAIGC (the liberation movement of Guinea-Bissau).

Throughout this period of the mid to late 60s a major feature of CYM life in Dublin was the Wednesday night lectures in Pembroke Lane. It was often a case of standing room only when we had some particularly prominent or controversial speakers. As the CYM was the “only game in town” from the point of view of radical youth politics, all sorts gravitated towards these meetings, which were usually open. Various opportunist elements thought the members of the CYM were fair game for their machinations, which included trying to influence and recruit our members for their own organisations, real or planned. People who were subsequently prominent in ultra-leftist politics argued their particular dogmas in an attempt, bluntly, to turn the movement away from the party.

The first manifestation of contemporary Trotskyism in youth politics in Ireland (heralded by the usual missionaries from across the Irish Sea) involved some disgruntled CYM members, lured by the sirens of instant revolution, who tried to win converts at our Wednesday meetings. They subsequently ended up in the various multiple varieties of Trotskyism: the League for a Workers’ Republic (with its Young Socialist organisation), the League for a Workers’ Vanguard (with its rival Young Socialist Organisation), and that’s even before the Militant Tendency manifested itself. As is usually the case, they mostly ended up either burnt out or resting in the Labour Party.

A more serious and organised challenge came from the so-called Irish Communist Organisation (later renamed British and Irish Communist Organisation). They had some fairly “heavyweight” Marxist-Leninist would-be gurus, who devised the notorious “two-nations theory.” Though they subsequently moved away from this position, they did enormous damage. This was limited in the CYM because of the ideological strength primarily of the IWP and its members in the CYM but very serious in the influence they weaved for this reactionary pro-imperialist analysis in the labour and trade union movement, specifically in the Labour Party, Democratic Socialist Party, and, most damaging, in the SFWP/Workers’ Party.

It must be said that the CPI never tried to interfere in the internal affairs of the CYM, letting us make our own mistakes and find our own way to whatever level of wisdom we eventually achieved. The CYM was consciously set up by the party as a broad socialist youth organisation, inspired by the teachings of James Connolly. It had no formal link to the party, though we all knew it was the party that had set us up, pointed the way ahead, and supported the CYM materially.

But most importantly, apart from the party members among the elected leadership of the CYM, party leaders such as Mick O’Riordan, Johnny Nolan, Sam Nolan and Joe Deasy and others, were always available to give us the benefit of their years of experience. And not just their experience: through the party we encountered such giants as Peadar O’Donnell, George Gilmore, and many others who spoke at our meetings.

One most important development in the late 1960s was the all-Ireland links that we developed with our comrades in the Communist Youth League (Northern Ireland) and that ultimately culminated in the achievement of the ambition, long cherished by older party members, of an all-Ireland Marxist youth organisation based (as stated in the manifesto of the Unity Congress in April 1970), “on the principles of Marx, Connolly, Lenin and Liam Mellows.”

But that will have to be the subject of another article.