■ Ethel Voynich, The Gadfly(1897)

Liam Mellows read this novel while awaiting his execution, along with the other condemned men imprisoned by the Irish Free State during the Civil War (1922–23) for opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which gave Ireland dominion status within the British Empire, rather than establishing an independent Irish republic.

His fellow-prisoner Peadar O’Donnell wrote: “It is a curious fact, which many of the Mountjoy prisoners must be easily able to recall, that it was around the days that the Gadfly was being widely read in ‘C’ wing; it is a tale of Italian revolution with a ghastly execution scene . . . MacKelvey . . . picking up the Gadfly . . . saying once more: ‘God, I hope they don’t mess up any of our lads this way.’ MacKelvey was to remember the Gadfly next morning.”

What was this book, so widely read by Republicans in Ireland, and the labour movement in Britain, in its own day?

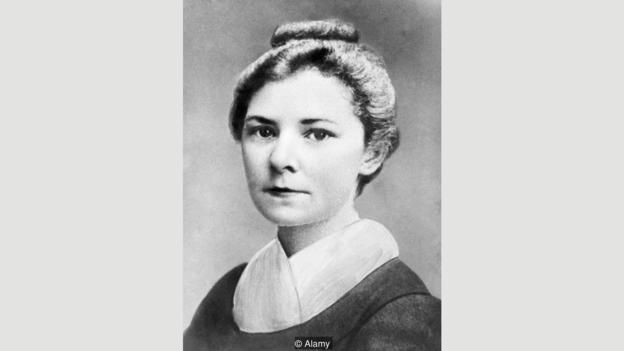

Its author, Ethel Boole, was born 11 May 1864 in Co. Cork, the youngest of five daughters of the renowned mathematician George Boole and Mary Boole, a psychologist and philosopher. Ethel’s father died shortly after her birth, and her mother took the family to London, returning to Ireland regularly during Ethel’s childhood. It was on one of these visits to Ireland that she first read about Giuseppe Mazzini, leader of the Italian Risorgimento movement.

This novel of revolution was published in 1897 and achieved cult status in the Soviet Union and China, selling millions of copies. Two film versions were made in the Soviet Union, one silent (1928), the other (1955) with a score by Dmitri Shostakovich.

Ethel Voynich was closely associated with revolutionary circles in Berlin, Russia, and London, where she married a Polish revolutionary, Wilfrid Voynich. From her experiences and circle of comrades she drew the stuff from which the novel is made. It is set in 1840s Italy at the time of its popular rebellion, the Risorgimento, against Austrian domination.

The novel’s main characters belong to Mazzini’s underground party, Young Italy, active in the national liberation movement. A thrilling plot roots the reader’s sympathy with the author’s. It is understandable how this book captured the imagination of readers who sympathise with movements against oppression and domination. “Several of them belonged to the Mazzinian party and would have been satisfied with nothing less than a democratic Republic and a United Italy.” It is obvious why the anti-Treaty prisoners, captured during the Civil War, identified with the characters in the book.

Reflecting historical fact, the novel criticises sharply the Catholic Church’s active opposition to the movement for a united Italy, expressed in a father-and-son conflict that deepens the import: an Italian reluctantly willing to sacrifice his son and the cause of freedom, and Italy’s future, for the sake of religion. The author leaves no doubt regarding her own stance—in fact the novel’s declared atheism must have contributed to its being banned by the Irish state in 1947.

The spirit of revolution is not limited to members of the Young Italy movement. It has covert support throughout the population, evidenced in many scenes in the novel. Ordinary people help the movement smuggle arms across borders, come to their personal aid; even prison warders back them. In fact in the scene referred to by MacKelvey the firing squad try to protect their secret hero.

So, at the end of the nineteenth century, at a time of international suffrage movements, we see evolving a new type of novel, one whose hero and heroine are revolutionaries and part of a revolutionary group. The central female character, Gemma Warren, is a woman who the movement respects highly. She is inspired not only by Voynich’s own experience but also by other women revolutionaries around the author. Gemma is not merely an emancipated woman: she is also a revolutionary woman, at the centre of the movement.

In this way she goes beyond the literary heroines of the late nineteenth century and anticipates the proletarian women that Gorky would write about. Voynich brings the revolutionary group not only as central to the novel’s plot but as a necessary part of this group, a new type of woman.

Given Voynich’s internationalism and experience, it is bewildering to find racist sentiments expressed towards South Americans and black people. This racism also affects the portrayal of women of colour. It seems that Voynich’s novel did not find much resonance in Cuba and other Latin American countries, nor in Africa, all waging heroic liberation struggles. Surprisingly, critics have not drawn attention to this aspect; instead, if they dislike it it is due to its unashamed atheism, so unusual for its time, or for its partisanship for a revolutionary movement.

Ethel worked with the Quakers as a social worker in the poor districts of London during the First World War, then left England for good about 1920, when she joined her husband in New York. There is no further information about active political work. Wilfrid died in 1930. Ethel returned to music, composing musical works, including the Epitaph in Ballad Form, dedicated to Roger Casement.

Soviet literati in 1955 discovered that Ethel was still alive in New York, aged ninety-one. This caused a sensation in the Soviet Union and also resulted in the payment of royalties. Ethel continued to live quietly with her companion, Anne Nill, who had once managed Wilfrid’s New York book business.

Ethel Voynich died sixty years ago, on 27 July 1960, aged ninety-six.