We are rarely forced to agree with Leo Varadkar, but it is difficult to find fault with his observation that the political tectonic plates in Northern Ireland are shifting. In the light of recent general election results, it is safe to say that not only is unionism’s majority eroding but its once-solid political monolith is fracturing. In a region long known for “not an inch” politics, these are important changes.

Not only did nationalists and unionists win an equal number of seats in the British House of Commons but three of Belfast’s four constituencies returned non-unionist MPs. No matter how this is spun, losing control of Ulster unionism’s birthplace is hugely significant. Moreover, when a strong DUP candidate lost the overwhelmingly unionist North Down constituency to Alliance, a new chapter was being written. Unionist hegemony is diminishing as divisions emerge between intractable hardliners and a more pragmatic element amenable to negotiation.

Of course in the flawed British first-past-the-post electoral system, results can sometimes be deceptive. Unionism, after all, still retains an overall majority in the Six Counties, and will continue to do so for some time. Nevertheless the latest election shows an inexorable trend, demanding measured evaluation.

Whoever else may be indifferent to a new reality on the ground, we can be sure that the ruling class in Ireland and Britain most certainly are not. We can also be certain that they are already planning for that eventuality, and are undoubtedly co-operating closely on the project.

Britain’s and Ireland’s ruling classes share one overriding ambition, and that is to retain their power, influence, and wealth. Whatever other differences they may have are set aside if or when their authority is vulnerable to challenge. Rapid or unmanaged change to the constitutional position in Ireland is viewed as a major threat to the status quo. From their point of view, the risk of violence is disturbing but comes second to their determination to remain in control.

So, as the outcome of the count became clear, the establishment north and south responded. Initial reaction was to divert attention from the constitutional issue with calls for the restoration of devolved institutions at Stormont. By way of adding authenticity to these calls, Julian Smith, secretary of state for Northern Ireland, claimed that a working Assembly and Executive were needed to address the dire state of the North’s health service. With the Royal College of Nursing planning the first strike in its history, this Tory MP seemed to have a point.

His case would have been more convincing, though, had it not been that a few months earlier the British Parliament had ignored the Stormont Assembly and passed legislation dealing with abortion and same-sex marriage.

But it wasn’t long before the national question re-emerged. On this occasion, however, it had an added dimension, in that hard-line unionism feared not only the removal of partition but also the imposition of customs clearance regulations in the Irish Sea. The air was soon filled with talk of border polls and the break-up of the United Kingdom.

And at that point a wide range of Irish conservatism also stood up to be heard, decrying any notion of even addressing the central constitutional issue.

The list of nay-sayers is impressive. In spite of feeling the “tectonic plates,” Varadkar dismissed the notion of unity as divisive. He was joined shortly thereafter by his old colleague in the austerity coalition Éamon Ryan of the Green Party. Colin Eastwood of the SDLP has already reserved a special place in Hell for such talk. Not to be outdone either were the two Martins, Micheál of Fianna Fáil and Éamon, Roman Catholic archbishop of Armagh, joining the do-nothing chorus.

The establishment here and in Britain can, nevertheless, only stall this process for so long but not indefinitely. The British ruling class has made it clear in word and deed that it has little or no interest in maintaining its present relationship with Northern Ireland. As a political entity, the North is in permanent deadlock, while economically the area is floundering. Compounding all this is inescapable evidence of changing demographics. All of which makes change inevitable.

The issue will then become one of what type of united Ireland will emerge. We know what the right-wing establishment north and south want, and it will be an Ireland offering little benefit to working people. Unity will be presented by Irish capitalism as a wonderland where we are embedded within the European Union, enthusiastic participants in NATO, and host (or in reality hostage) to a phalanx of American transnational corporations and international financiers.

To ensure that we are not presented with such a fait accompli, the left must rise to the challenge and recognise this as an issue we cannot afford to ignore and a reality that will not go away. It is imperative that this question is not abandoned to conservatives and pro-imperialist free-marketeers.

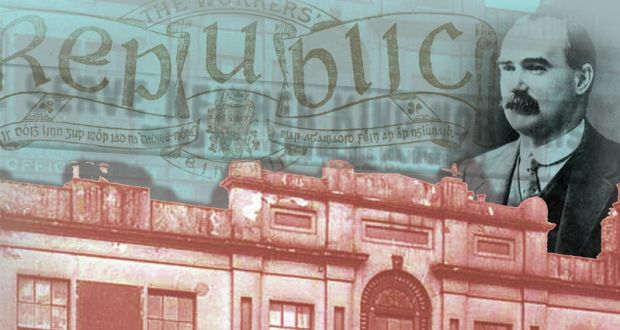

With support from socialist republicans and communists, the Peadar O’Donnell Socialist Republican Forum is organising a Left for Unity campaign that aims to highlight these issues and assist in the work towards achieving the goal of a workers’ republic. The campaign welcomes support and contributions from throughout the left. Our opponents are prepared, and so must we be.

■ Have a look at the Forum on Facebook at “Peadar O’Donnell Socialist Republican Forum.”