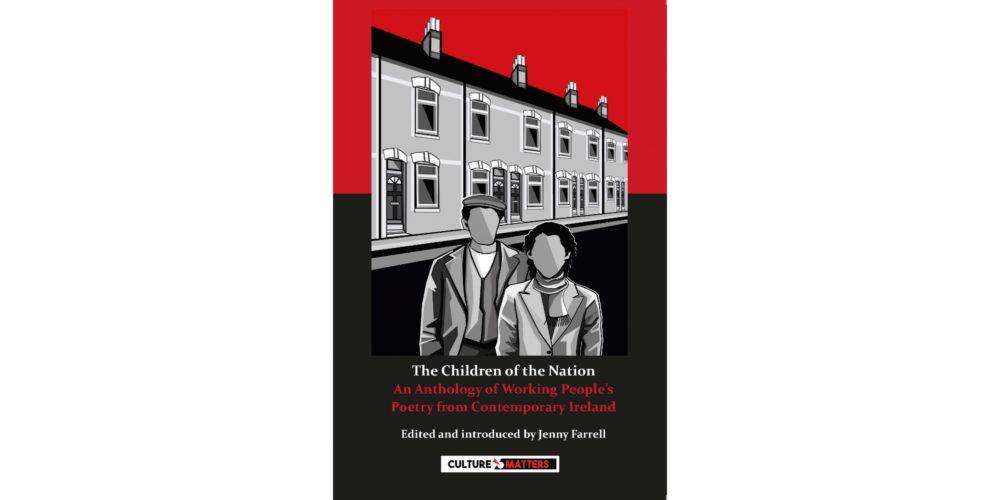

Jenny Farrell (editor), The Children of the Nation: An Anthology of Working People’s Poetry from Contemporary Ireland (Newcastle upon Tyne: Culture Matters, 2019).

This anthology deals with the identity of the working class, the marginalised, people in precarious employment, the unemployed, the homeless. The title of the collection recalls the pledge made in the Proclamation of 1916.

Most of the literature we read deals with comfortable middle-class lives. Here the authenticity of sixty-seven working lives unfolds before our eyes, making for a genuinely unique volume whose contributors hail from all over Ireland, south and north, and from both sides of the sectarian divide.

Scott McKendry writes about geese migrating in winter to the Shankill Road, Belfast: “They come at the end of November, | fleeing the Icelandic freeze; swapping the aurora Borealis | for murals in memory of Stevie McKeag | and Bucky McCullough; || and those for Cromwell, Cúchulainn, Luther || and Iron Maiden’s Eddie the Head | dressed up as The Trooper, moonlighting for the UFF.”(“Duck, Duck, Goose”)

Just over on the Falls Road, Gearóid Mac Lochlainn opens on another season, “Heatwave Eile”: “Bhí an boladh bréan ag análú | ó leithreas briste síos sa Choirceog Beach | róláidir inniu. Dofhulaingthe. | Bhí mo phoill sróine ag damhsa | le sewage an heatwave órga | a ghlac seilbh ar an chathair | seachtain ó shin.”

The collection includes poets from the rural and industrial working class as well as those in traditionally middle-income jobs, forced into short-term contracts by a neo-liberal economy. “Working class” has come to encompass all these groups.

Homelessness is a main theme, casting dark shadows in manifold manifestations. One of these is an overarching feeling of alienation from mainstream society: “The greedy | rub their hands | with glee in much the same | way now as | they did back then. Over | a hundred | and seventy years changed | nothing. The | rich get richer and the | poor grow more | poor, and most of us have | nowhere to | live. For there ain’t no home | in Dublin.” (Ross J. Walsh, “Black 47”)

Then there is the very real social violence against more than ten thousand homeless people. Sarah Boyce evokes this for Belfast: “Its brick-bled and rain-wept heart, | whose municipal vision cuts through | its public benches; | no space here for homeless bums | Meanwhile, down a high street entry | great black-backed gulls | span a crumpled sleeping bag | in search of carrion. (“Its Beating Heart”)

Other writers, such as Rita Ann Higgins, address unemployment with unrepentant sarcasm: “Hey Minister, we like your suit | have a bun, where are our jobs? | But there was no point; | he was here on a bun-eating session | not a job-finding session. || His hands were tied. | His tongue a marshmallow.” (“No One Mentioned the Roofer”)

The book contains the views of both immigrants and emigrants. Peggie Caldwell, from rural Donegal, writes of this experience, continuing: “Fallacies echo: Live Register lowest it’s been since 2008. || But in these hills the white noise rebounds, | the absence of fledgling song deafening us.” (“Still They Go”)

Along with the British socialist publisher Culture Matters, the Irish trade union movement was instrumental in bringing this anthology about.

■ Available from Connolly Books (Dublin), Charlie Byrne’s Bookshop (Galway), Vibes & Scribes (Cork), and on line from www.culturematters.org.uk/index.php/shop-support/our-publications/item/3184-the-children-of-the-nation