Robert Tressell’s book The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists is the first important working-class novel in English literature, written between 1906 and 1910 and first published posthumously, and very abridged, in 1914.

The working class has championed this novel about their experience and written from their own point-of-view like no other working-class novel in Britain.

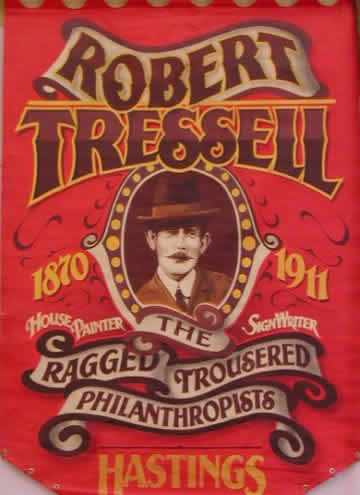

Its author, Robert Noonan, was born in Dublin in 1870. The family moved to London, Robert trained as a sign-writer and decorator. From 1894, Tressell spent some years in South Africa, involved with the Trade Union movement and helping organise an Irish Brigade to fight on the Boers’ side against the British. In 1901, Tressell settled in Hastings and joined the then only Marxist group, the Social-Democratic Federation. Frequently unemployed, Tressell wrote the Philanthropists. He died of TB in a workhouse hospital in 1911 and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

The transition from industrial capitalism to monopoly capitalism at the end of the 19th century, necessitates a change to the traditional novel plot. Cash Nexus replaces personal “stories” between members of opposed classes. Tressell portrays honestly typical characters in typical circumstances and develops a collective “hero”, thereby revolutionising the genre and contributing to socialist realism in the English novel.

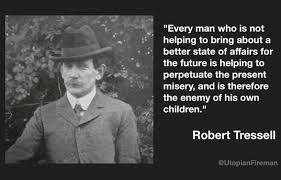

The Philanthropists presents an epic portrait of working-class existence in the early days of imperialism. For the first time, an impoverished group of workers takes centre-stage in an English novel. They are duped by what they read in The Daily Obscurer and Tressell castigates them for the ‘philanthropic’ acceptance of their destitution, their acquiescence that a good life is not “the likes of us” and that their children should inherit this lot.

The boss Rushton (rush-it-on) and his middle-men force the workers to hurry and slobber the work, use inferior materials, while charging high prices, and looting the premises for their own benefit. They threaten the casual labourers with unemployment, effectively the workhouse and destitution. They control the workers politically through the city’s council and through the church. Thus, their economic power is copper-fastened by hegemony of the political and religious spheres, as well as domination of the ‘private life’ domain of the pub.

Working-class life is traced from the cradle to the grave, from Easton’s baby, through to Jack Linden, who dies in a workhouse after a life of hard labour. While the working-class characters are individualised, the bosses are types. Working life potentially encompasses all aspects of truly human living, while the ruling class is beyond consideration as a human way of life; its purpose being to thwart the workers’ free development. This is a brilliant reversal of the usual pattern of individualised middle-class lives and worker stereotypes, still propagated in contemporary novels.

Never before in the English realist novel, had the actual labour process been central to the depiction of class struggle. Tressell reverses the assumption that life begins where work ends – work is essential to fully lived human life. A character’s attitude to labour is a touchstone of his or her humanity.

The book’s individual hero is Frank Owen, named after the utopian socialist Robert Owen. His decorative painting of the drawing room in the Moorish style is a supreme example of fulfilment through work. During this work, the socialist Owen achieves his fullest humanity and the bosses lose control of him.

Owen strives to persuade his work-mates of his way of thinking. His dinner break lectures on Marxism comment on the novel’s events. A central talk is where Owen explains, “Money is the real cause of poverty” and describes “the Great Money Trick”. Using bits and pieces from the dinner baskets, Owen illustrates the creation of surplus value. Although he only reaches some of the workers, the portrayal of the others is not negative. They engage with him and take an active part in these lectures, by helping to dramatise the examples. In these scenes of theatrical enjoyment, their collective reaches its highest development.

An important theme in the novel is the scamping of work. Misery commands the men non-stop to “slobber it on”, cover dirt, cracks and structural weaknesses for long enough to pocket the profits. While this is typical capitalist work ethic, it also epitomises the general drive to alienation in imperialist society and furthermore becomes a symbol for the entire imperialist set-up, where putrefaction, corruption, fraud and structural weaknesses are covered with a shoddy façade of illusory luxury and ineffectual half-measures.

Working people today easily recognise the ‘slob-it-on’ work ethic of ever less resources, fewer people to do jobs, deteriorating wages and conditions, part-time work, unemployment. All who sell their labour are essentially in the same boat.

Over 100 years after its first publication, The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists continues to be a revelation for most readers, a novel of the utmost relevance today, as a book that describes the world as it is.