Industrial relations law often works on the assumption that both sides of a dispute are reasonable entities: employers won’t exploit or take advantage of their workers, and in return the workers won’t ask for “too much”; and, just in case, we have trade unions to try to keep the playing-pitch level.

Given this premise, it is easy to see why some trade unions can feel obliged to take a conciliatory tone about “excessive” industrial action. The broad trade union support (officials, not necessarily workers) for the introduction of the Industrial Relations Act in 1990 to “ban ridiculous strikes” is one such example.

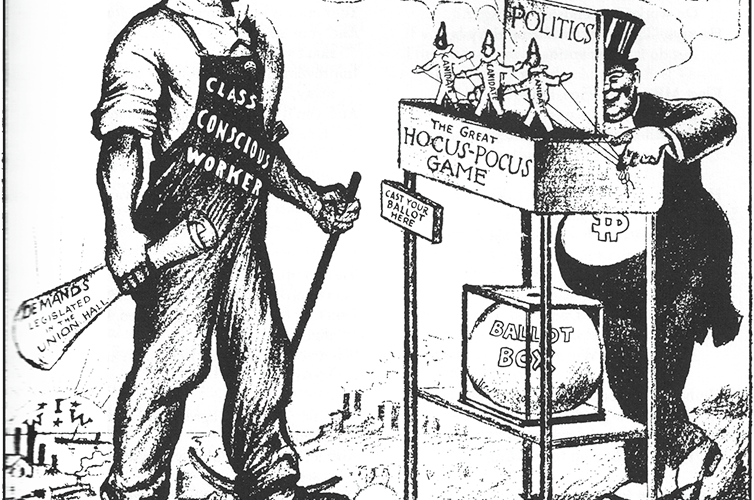

Trade unions are pressured by political parties that they align with, by unfair media bias and a fear of losing public support to back laws that restrict their own power. They need to be seen as reasonable and willing to play ball by the rules. That these rules are written by, and for the benefit of, the capitalist class is somehow beside the point. And even where the union movement has strength, this strength is still justified on the bosses’ terms.

In 1977 Québec introduced anti-scab laws that prohibit employers under picket or who have locked out their employees from hiring temporary replacement workers—scabs. Articles 109.1 to 109.3 of the Québec Labour Code states that employers can replace striking workers only with management personnel working in strike-bound establishments who were hired before the beginning of the strike.

These measures were introduced with the twin goals of preventing violence and making labour conflicts shorter. The trade union movements of Québec, British Columbia and Ontario,* where these laws have been in force, still make these arguments to defend the legislation. Shorter and less frequent strikes means that strikes have less of an economic impact, and that total productivity, the holy grail of capitalism, isn’t harmed too greatly. However, studies have shown that strikes have, generally, not been shortened.

One study in particular, by the American researchers Peter Cramton, Morley Gunderson and Joseph Tracy,† shows that the prohibition on the hiring of replacement workers is actually associated with more frequent and longer strikes. In fact it increases the probability that a strike will occur, and that it will last longer, contradicting the trade union movement’s earnest claims.

So why are these strikes lasting longer?

The blame for strikes in this study (and similar ones) always rests with the workers, as if industrial action is taken in a bubble and not brought about by employers’ actions, or lack thereof. A demand for an increase in wages is treated as the whim of stroppy workers, refusing to get along, instead of being demanded as a result of increased company profit, an increased work load, or a necessity to keep up with inflation.

When industrial action is framed as an action that unions and workers should feel guilt over, it nullifies the central role that business-owners play. It is not the unions or the workers who protract these disputes when anti-scab laws are in effect but the employers themselves. Employers know that when they have no ability to sidestep the striking workers by bringing in scabs, any concession they make to these workers will not be one they can take back with any ease.

Class conflict that develops the consciousness of workers brings out the worst instincts of the capitalist too and shows the true relationship of worker and boss. It is naïve of unions to pin their defence of the laws that benefit their members on the measure of fewer days lost to strikes when the capitalists can prove this wrong by embracing their own unwillingness to negotiate.

By appealing to capitalist arguments of productivity to justify workers’ actions they acquiesce in a capitalist world view, a world view that is an anathema to the trade union movement.

Bizarrely, another rarely mentioned but more important effect of the anti-scab legislation is the one it has on real wages. The same study finds that the ban on replacement workers leads to an increase in real wages of 2 per cent per year, on average. The authors estimate that the greater wage gains exceed the losses made by union members in terms of additional strike days. This should be the union’s argument, not a defence but an acknowledgement that the gains a strong working-class movement can make by protecting themselves are in excess of their cost.

Union numbers are in steady decline, and there are many reasons for this: the face of work is changing, precariousness is commonplace, and the job for life is dead. But this should not be new or unfamiliar territory for trade unions aware of their own history. Job security is relatively recent, and it was not a gift from the employers but one that union members won through struggle.

It seems to the lay person that unions, as behemoth, faceless organisations, often have more in common with the bosses than with the workers they claim to represent; and it isn’t such an absurd view when the unions have begun using the bosses’ ideas and the bosses’ language. Wouldn’t it be expected that they will eventually share the bosses’ disgust?

The ill-used excuse that a trade union is only as good as its members rings false when it is the place of the union to educate and empower its membership to become a more militant and class-conscious one. To be effective, trade unions must make no excuses for the actions of their members but defend them and have no shame for the reasons they do it, even if it means rewriting the rules.

*Ontario rescinded the anti-scab law in 1992 in favour of a prohibition on the use of professional strike-breakers.

†Peter Cramton, Morley Gunderson and Joseph S. Tracy, “Impacts of strike replacement bans in Canada,” Labour Law Journal, vol. 50 (1999).