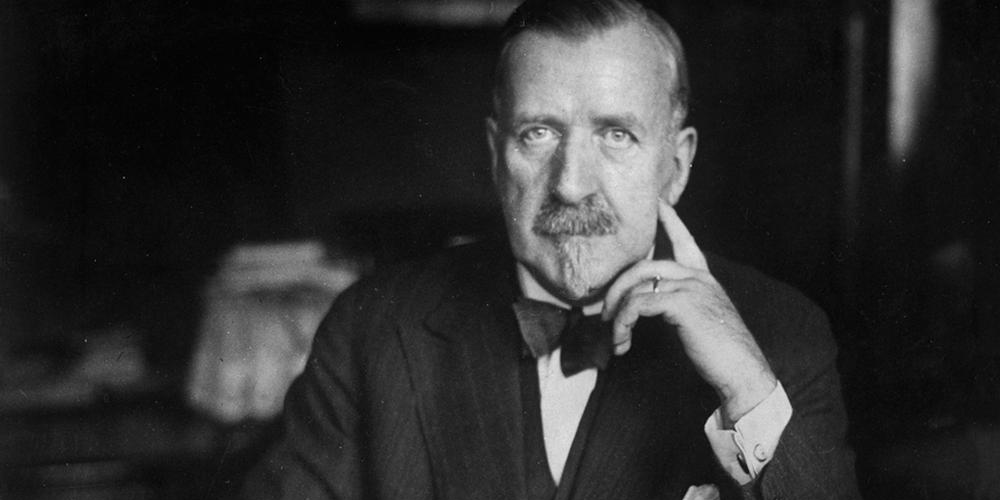

Heinrich Mann, brother of Thomas Mann and in his own right one of the most significant German writers of the 20th century, died in exile in California 75 years ago, on March 11, 1950. His literary work, deeply concerned with social justice and political change, remains relevant today. Mann’s writing is defined by sharp criticism of the prevailing social conditions of his time, particularly the power structures of the Wilhelmine Empire. His novels are literary masterpieces and critically reflect the spirit of an era.

The establishment of the German Empire in 1871 marked the start of an authoritarian nation-state dominated by militarism, obedience to authority, and nationalism under Prussian leadership. This system represented the interests of the ruling classes – the landed aristocracy and the bourgeoisie – who maintained power through repression. Under Wilhelm II after 1890, the empire became an aggressive imperialist power, reflecting capitalism’s need for global expansion and leading to World War I.

Heinrich Mann’s The Loyal Subject (1914, publ. in English 1998) captures the essence of Wilhelmine Germany and critiques the bourgeoisie’s role in supporting the ruling structures. The novel forms part of Mann’s Trilogy of the Empire, which includes The Poor (1917) and The Head (1925). These works are milestones in political literature, engaging with the societal developments of the time and advocating for the overthrow of the existing regime, which eventually culminated in the revolution of 1918.

The Loyal Subject, Mann’s most famous novel, is both a masterpiece and a sharp social critique. It satirises the German citizen under Wilhelm II’s rule, exposing the mechanisms of power, submission, and opportunism within the empire. The central character, Diederich Hessling, embodies the type of submissive subject who both blindly submits to authority and seeks power to oppress others. Hessling evolves from a fearful young man into a ruthless industrialist and local politician, showcasing the dehumanising effects of authoritarianism.

Hessling’s upbringing in an authoritarian household and his exposure to a teacher who glorifies the Franco-Prussian War exemplify the deep-rooted chauvinism in German society. The teacher’s teachings of hatred and conquest prepare Hessling for future wars, reflecting how the bourgeoisie was conditioned for imperialism. The novel’s setting in the 1890s, in the fictional town of Netzig, is grounded in real historical events such as the 1892 street riots, the 1813 Wars of Liberation anniversary, and the Zabern Affair, creating a vivid portrayal of the era.

Mann parodies the Bildungsroman (novel of education), but Hessling’s “education” contrasts with liberal humanistic ideals. Rather than fostering moral maturity, his upbringing moulds him into a tool of oppressive power: self-denial replaces self-discovery. He becomes a “tough” man, submitting to authority unquestioningly, embodying the corrupt spirit of the times. His interactions with others, particularly women, reveal his emotional coldness and opportunism, mirroring his submission to societal norms and power structures.

Hessling’s rise within business, the military, bureaucracy, and the church reflects how submission and conformity to the ruling structures enable personal success. His character captures the essence of the imperialist bourgeoisie: greedy, power-hungry, and dehumanised. The novel also contrasts the declining liberal bourgeoisie, represented by the character of old Buck, with the emerging imperialist type embodied by Hessling. Buck’s tragic demise symbolises the destruction of humanistic ideals by the rising imperialist order.

Mann’s view of society, however, was not without contradictions. His perspective led him to see the emerging society as dominated by a single, pervasive mindset, which also shaped his depiction of social democracy as part of the capitalist subjugation system. The figure of Napoleon Fischer, a labour leader and Hessling’s antagonist, exemplifies this simplification. Fischer’s failure, despite his insights into class struggle, is attributed to his opportunism.

Despite these contradictions, Mann’s work remains highly significant. His novels are not only literary masterpieces but also highlight the necessity of societal change. Mann’s optimism, particularly his hope for a revolutionary upheaval, gives his works an open-ended perspective. In The Loyal Subject, this is symbolised by a thunderstorm disrupting an establishment celebration at the novel’s end. The storm, coming from “where the masses were,” foreshadows the inevitable revolution.

The Loyal Subject is both a sharp artistic critique of the bourgeois-aristocratic power structures and a work with profound historical and political depth. Mann successfully condenses the economic-political processes of his time into a literary image, exposing the moral corruption of the system. The novel raises essential questions about power, subjugation, and resistance, pointing to the responsibility of artists to expose power relations and effect change.

Heinrich Mann wrote in his famous 1915 Zola essay: “An empire that has been based solely on violence and not on freedom, justice, and truth, an empire where only orders are given and obeyed, profits are made and people exploited, but never respected, cannot triumph, no matter how great its power.” His words proved prescient, resonating in the aftermath of both World Wars, and remain valid for all imperialist wars.

Heinrich Mann’s literary legacy urges a critical examination of how militarism and imperialism systematically distort and damage individuals’ psyches, advocating for a humane society. On the occasion of his 75th death anniversary, it is worth rediscovering his work and revisiting the questions of justice, reason, and human dignity contained within it. Heinrich Mann remains an author whose voice continues to resonate today.