For the purpose of this contribution, decadence is primarily demonstrated in class self-indulgence. Media discourse, synchronised with election cycles, demonstrates this well, as the capitalist class and its state clientele put focus on issues divorced from those of the working class. At those few points of convergence, we see the crises of the working class portrayed as opportunities of the capitalist class. The working class is expected to align with one of the capitalist options on offer, and hope that somehow this will benefit workers in some perverse trickle-down fashion. Furthermore, the working class is conscripted into participation in this discourse, and thus we witness a separation of interests and ideas, inherent to class struggle, manifesting in a decadent self-indulgence.

The core issue here, I claim today, is in the unhistorical treatment of the past, and consequently the present and the future. From a liberal, fundamentally unmaterialistic and individualist perspective, history is a collection of unrelated experiences with no limits on variance, structure, or possibility. It maps onto the individual experience of life: episodes divorced from context, left to chance and unexpected developments.

It is no wonder that with such a dominant, naturalised perspective on history we are told to “wait and see” what will happen in Syria after regime change. The effects on the Middle East, we hear, cannot be predicted. The imperialist line attacks and offers liberal values as the frame of an ahistorical future, with two key points to this vision: being for good and against bad things and being ready to exceptionalise the snapshots of history it disconnects in its denial of historicity.

While putting together this contribution, I saw an advertising slogan for a multinational, claiming that “Future will not wAIt”. The stylised “AI” there places artificial “intelligence” in the role of a force of nature that develops independently and rapidly and threatens those who do not adapt to it early. In the tradition of capitalist competition, the AI that doesn’t wait is a zero-sum game and latecomers will suffer. The framing of technology as an independent force is not only ahistorical in its failure to recognise its social feedback loops; it is also a manifestation of the snapshot exceptionalisation we mentioned previously. Sam Altman of OpenAI was in the news recently, claiming the need to revise the social contract in light of AI. An exceptional snapshot.

In another exceptional snapshot, we are to look at 2025 in the US, and the new administration in the White House. We are told that, once again, we are waking up in a fascist stage of development, abruptly transitioning into a symbolically heavy bad thing we don’t like. A vox pop I recently saw had German people telling Musk, after his performance at the Trump inauguration, not to go down the Nazi path because Germany tried it, and it did not go well. Comical as it sounds – “don’t be a Nazi because it didn’t work out for the Germans” – it illustrates simultaneously the exceptionalisation and the empty non-analysis of simply favouring good things over the bad. There is no way to interpret historical processes and understand how we reached this historical point with these tools on offer. The farthest we can get is the now popular perception of fascism as a high fantasy concept: Orcs, Saruman, somehow Palpatine returned.

This approach separates concepts sharply, in definition and in time, confidently disconnecting connected processes, and readily claiming the end of unending processes. Extending Horkheimer’s famous quote, Domenico Losurdo writes: “Whoever is unwilling to talk about colonialism should also keep quiet about capitalism and fascism.” If we pause and reflect on this, we will see the ahistorical liberal sense of colonialism as a thing of the past, and the possibility to keep fascism away from capitalism by maintenance of some kinder, gentler imperialism. To accept such a worldview requires abandonment of historical understanding. That is the only way to make the claim, with a straight face, that Trump is somehow the first imperialist president of the US. In tandem with this claim, comes that of “this is not who we are.”

It is a fascinating phrase, in all honesty. It could be fully dialectical if it involved the consciousness of how “we” change and how our understanding of our position is contextual and intertwined with the environment and relations we are in. But it is not, it is an outright denial based on the same rejection of bad and embracing of good that is merely a static claim, and not an interpretation, a guiding principle, or a force in history. It’s also allowing that “anything could happen” once again, because if we can be something we’re not, we can truly be anything.

Such denial of the science of history allows going against the arrow of time and lets the shallow analysis ahistorically invoke anachronistic concepts in explaining the imperialist reality of our times. One such example is that of referring to the techno-financial capital structure as feudalist, while clearly being at the bleeding edge of the capitalist mode of production. In mid-20th century Middle East, in a much less developed setup of capitalist forces, Mahdi Amel skilfully dismantled the idea of feudalism somehow surviving in colonised lands once the coloniser introduced the extractive setup of capitalist relations. The capitalist mode of production is the dominant denominator of the system, not the superficial emotional reference to yet another high fantasy idea of feudalism that somehow returns. Finally, while we speak of Amel, we still owe it to Losurdo to speak of colonialism more.

Colonialism, in Amel’s words and in historical practice alike, does not end with the removal of the colonial military force. With the process of subjection of the bourgeoisie of the colonised to that of the coloniser and making it the clientele of the imperialist structure, the decadent self-indulgence of the capitalist class does not remain contained and gets aggressively exported beyond the imperial core, remaining a global issue. Hence, a global imperative: always historicise.

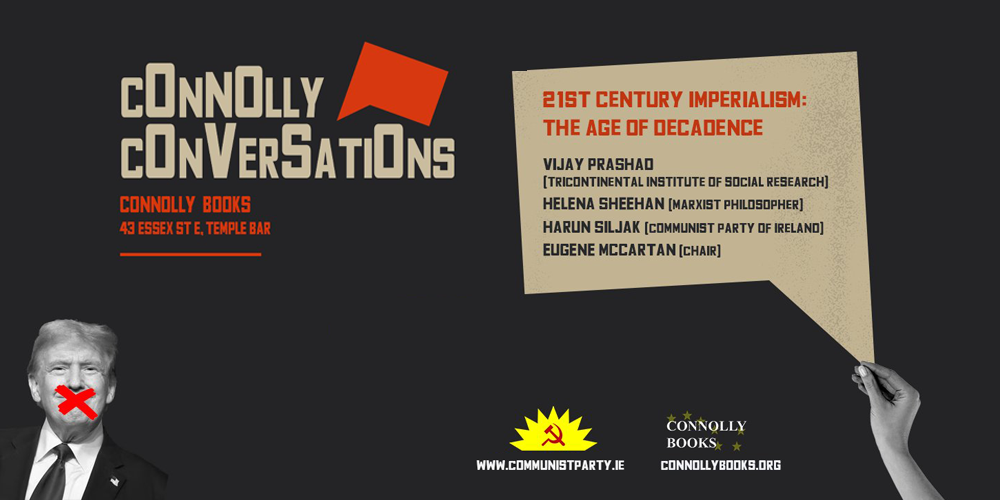

Harun Šiljak is a lecturer, researcher and author based in Dublin. His work falls in the broad category of Marxist analysis of the uneasy relationship between institutions, technology and creative practices. This paper was presented at the January Connolly Conversations event, titled “21st Century Imperialism: The age of decadence”, held in Connolly Books, Dublin.