For decades, New Books editions of Connolly’s writings were the main resource for readers seeking the word of James Connolly in print. The two volumes of Connolly’s Collected Works and pocket versions of Labour in Irish History remained bestsellers in New Books (later Connolly Books), but the story of Connolly and his writings does not end on those pages.

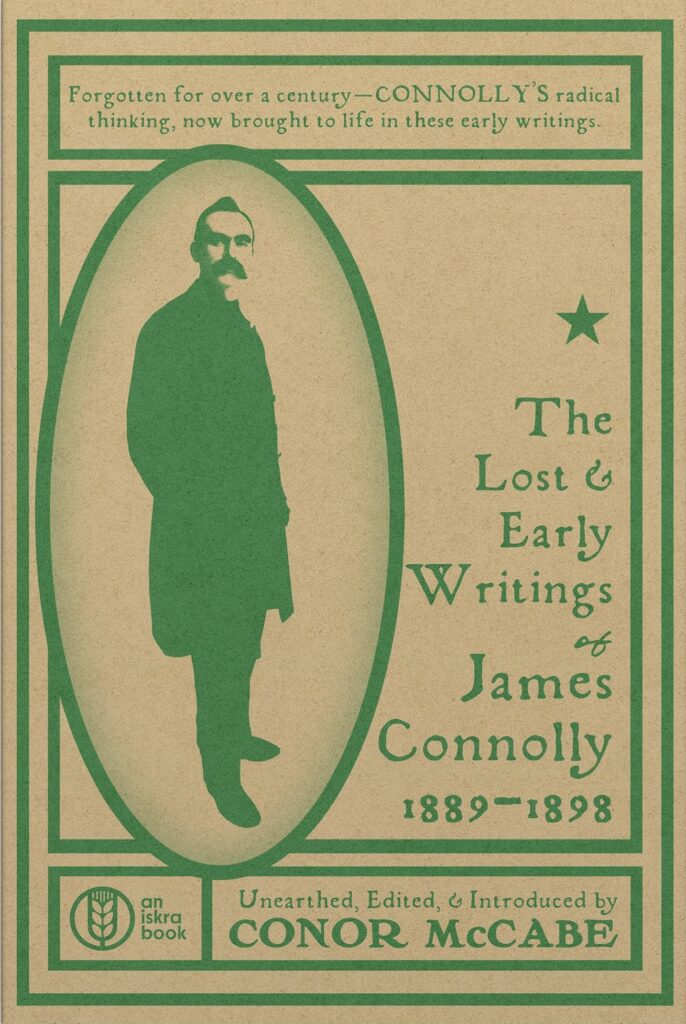

Conor McCabe set out on a mission to correct and complete the record on Connolly’s publication with his newest volume, published by Iskra Books. McCabe’s collection combines newly found articles and letters of Connolly with lost fiction pieces he wrote, and previously partially published works. McCabe also uses this space to trace the line between publications and the activity of James Connolly and his brother John (easily confused, especially in the early days). Finally, he disputes the claims of Connolly’s army career described in Desmond Greaves’ The Life and Times of James Connolly. While Greaves is not the only author and contributor to Connolly literature called out in McCabe’s writing, his methodology and sources receive McCabe’s scrutiny in detail. This suggests space for more research and more discussions about key events in Connolly’s life, a conversation which will surely continue in historians’ circles.

Connolly’s writings are, quite naturally, historicised through his personal circumstances and the changing material conditions in Ireland and the world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The specific context of Ireland has seen Connolly’s work re-examined through the perceived contradictions of nationalism, internationalism, and socialism: oftentimes a shift from an earlier, red socialist Connolly to a green nationalist Connolly. This notion, not limited to Connolly’s contemporaries like Seán O’Casey, is strongly denied by McCabe. In his study of Connolly, McCabe finds no delineation between an early and a late Connolly, or any accident that would make Connolly become a republican at expense of his socialism. McCabe mocks the idea of separating Connolly’s socialism and republicanism, and rightfully cites the proud anti-imperialist, anti-colonial socialist tradition in the rest of the colonised world as the ideological framework to which Connolly’s thought belongs. In such claims, McCabe is not alone: Michael O’Riordan’s foreword to the Collected Works echoes the same socialist republican thought. It is not accidental that Revolutionary Warfare writings of Connolly, edited by O’Riordan and published by New Books in 1968, were translated in Beirut into Arabic only a few years later.

In the part of the introduction dealing with Connolly’s socialist republican vision and its roots in anti-imperialist struggle, McCabe dismisses the idea of Connolly’s conversion to republicanism being caused by a “Fenian uncle” he had: “Maybe Mariátegui, Cabral and Amel simply had Fenian uncles.” (p. xvi). This joke is not unlike the humour and the sting of Connolly’s own writing in this volume: it is a collection of vibrant texts, reflecting conditions of the time, strong analysis, and the skill of Connolly to keep the reader interested in his short, and yet informative writing style. His fiction is a delight to read as well; thanks to McCabe we can now speak of Connolly as a short story author with an interesting style, and skill to tackle issues in fiction that theory-writing would not efficiently address.

Very readable, aesthetically well-designed, and logically organised, this new exciting volume makes an important contribution to scholarship, sets standards and expectations for new works in Irish socialist history and, maybe most importantly, offers a new, accessible route for new readers of Connolly. Connolly of the Lost and Early Writings is as sharp and as methodical as the Connolly of the later days, but some readers might find him less intimidating in this edition.

The Lost & Early Writings of James Connolly 1889-1898, unearthed, edited & introduced by Conor McCabe (Iskra Books, 2024) is available from Connolly Books, Temple Bar.