In geology, the periods and smaller epochs of Earth’s past are named by the region in which they were first determined as such, or by their characteristics. Well-known periods are the Carboniferous, for its ample coal deposits, and the Jurassic, for the Jura Mountains, where it was first identified. The beginnings and ends of these times are often marked by global, sometimes catastrophic changes, leaving visible traces on the Earth.

We are now in the Quaternary Epoch, defined by the cyclical growth and retreat of the polar ice caps known as Ice Ages. More specifically, within this period we live in what is formally known as the Holocene Epoch, which is the current warm period after the end of the last Ice Age. Although humankind has wandered the Earth for over a million years, it is during this stable period that human civilisation developed into what it is today.

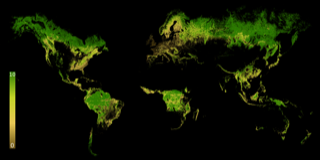

In the last couple of decades geologists have proposed a new epoch: the Anthropocene, or age of humans. There is no real consensus on when this epoch begins, however. Some propose the advent of farming, which has resulted in widespread deforestation; others choose the detonation of the first nuclear bomb, stamping its signature isotope mark on the world.

No matter what criteria you choose, one thing remains clear: human activity is reshaping this planet on such a scale that it will remain visible hundreds of millions of years into the future. As we are today, the world is facing environmental disaster, with a loss of biodiversity that is rivalled only by the greatest mass extinctions from the ancient past and a climate that is changing faster than this planet has ever seen in the past 55 million years.

In the face of this crisis we are told that the blame lies with us humans as a whole, and that we as a global society must rectify the damage. Humankind, however, is not a homogeneous group, with a common value and behaviour. Therefore the Anthropocene is not the result of humanity as a collective—on the contrary, it is the result of the actions of a particular group of people from particular parts of the world.

The “we are all to blame” attitude that is forced upon us is therefore mere gaslighting—a way for both capitalism and imperialism to externalise the costs of their reckless exploitation of the planet.

While the relationship of the working class with the capitalist class with regard to exploitation cannot be directly translated to nature, there are definite parallels. Capitalism will always seek ways to increase profit or else will face elimination by itself. There are two ways to realise this: increase income and reduce costs. Therefore the capitalist class is inherently motivated to do as little as it can get away with to protect workers from the harm its methods cause.

Simultaneously it actively withholds knowledge of health risks. This way it keeps the internal costs of protection and wages down. Once workers eventually fall ill it will seek ways to get rid of them, thus to externalise the costs to society of their recovery.

This applies to nature as well. Exxon-Mobil and Shell knew since the 1980s about the dangers of altering the make-up of our atmosphere with the unrestrained burning of fossil fuels. Instead of taking responsibility and limiting the harm already done, the knowledge was buried and actively fought, in a similar way we have seen with leaded petrol, tobacco, and the damage to the ozone layer.

Now, forty years later, we have arrived at a point where the costs are becoming a reality and nearly impossible to ignore or deny.

Here is where capitalism is attempting to externalise the costs to a world that had no part in their reckless exploitation, with its message that we are all to blame. After all, we are in the Anthropocene: the age of humans.

This applies more so to the global south, where developing nations, after being robbed of their natural resources, are told to limit or halt their development for the sake of the environment. In an attempt to not take responsibility and divert attention, fingers are pointed at countries such as India, which, despite having a population twenty times higher than Britain, has in total contributed only half of Britain’s cumulative carbon emissions.

We are told that we are all in the same boat, that we must all contribute, no matter our part in the cause of the staggering problems that are facing us. Perhaps one could indeed regard Planet Earth as a ship, one where the elite travel first class, with priority access to the lifeboats, while the lower decks are left on their own.

No matter how “green” we may make our personal lifestyle, capitalism will always remain unsustainable.