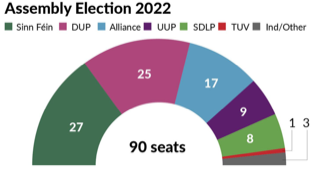

A historic step forward was taken on the road to Irish freedom when the nationalist party Sinn Féin won more seats in the recent Northern Ireland Assembly than the pro-British Democratic Unionist Party. Sinn Féin secured 29 per cent of the popular vote, to become the largest party, with 27 of the 90 seats. The DUP secured 21 per cent and 25 seats.

Since the British state frustrated the establishment of an independent Ireland through partition over a century ago, unionism has ensured a subservient regional government in the north-east of Ireland. In return it expected, and still expects, to impose its rule over the nationalist minority in the north.

The election on 5 May has ended that as a working assumption of Northern Ireland politics. In the words of the general secretary of the CPI, the opportunities are now here “to strengthen the national content in the class struggle and the class content in the national struggle.”

Under the power-sharing arrangements of the Belfast Agreement (1998), Michelle O’Neill of Sinn Féin, as leader of the largest party in the Assembly, is now entitled to become First Minister in the next governing Executive, unseating the DUP from that position. While Sinn Féin did not emphasise Irish unity in the election, it has made it clear that it anticipates a border poll within the next five to ten years.

Ironically, also thanks to the Belfast Agreement and its power-sharing architecture, the DUP is able to block the appointment of a Sinn Féin First Minister. The DUP is refusing to exercise its right as the largest unionist party to nominate a Deputy First Minister. That must be done in order for the First Minister’s post to take effect. Without those posts filled, an Executive cannot be formed.

The DUP is also blocking the necessary cross-party election of a speaker (chairperson) of the Assembly, thereby preventing it from meeting.

The history of the struggle for Irish freedom has never been straightforward. Today the development of national sovereignty in Ireland is constrained by three competing and collaborating global powers: Britain, the European Union, and America—what the Communist Party of Ireland describes as the “triple lock of imperialism.”

British imperialism not only continues to maintain its direct political power in Northern Ireland but also has a major economic presence on both sides of the border. European imperialism is seen in its economic regulation and political influence on both sides of the border. This will increase as the EU moves ever closer to becoming a federal superstate, including its militarisation, which undermines Irish neutrality. US imperialism exerts its control through its economic presence, its political influence, and its abuse of Irish neutrality through the military use of Shannon Airport.

Understanding the internal dynamics of Northern Ireland politics has to take account of this triple lock. The internal accommodation between unionism and nationalism achieved by the Belfast Agreement was brokered by the British, the EU, and the Americans. Despite its international fanfare, the agreement was inherently unstable. Since being set up in 1998 the Assembly has been suspended on five occasions—once for five years (2002–07) and recently for three years (2017–2020). At the start of this year the DUP First Minister resigned in protest at the Northern Ireland Protocol; so at the time of the recent election there was only a caretaker Executive and Assembly.

The Northern Ireland Protocol places a customs border in the Irish Sea between Britain and Northern Ireland. This was agreed as part of the negotiations on the United Kingdom leaving the EU. As Ireland has the only land border between the UK and the EU, it has had an important place in those negotiations.

Both sides have been aggressively determined to defend and advance their own strategic interests but making great play of wanting to protect the Belfast Agreement.

Just as the leadership have wholeheartedly committed themselves to the British side in those negotiations, the leadership of Sinn Féin, in its pursuit of power through political respectability, has committed itself to the EU side. The unionists have clearly been used in those negotiations by a British Prime Minister who promised “there will be no border down the Irish Sea—over my dead body” and then agreed just such an arrangement.

Sinn Féin can expect the same treatment from the EU in both the North and the South when it attempts to pursue the more radical aspects of its programme within the neoliberal restrictions of the EU.

The Belfast Agreement was premised on the continuing existence of the political and communal divide and the need to ensure cross-community agreement on important decisions. Elected representatives are required to designate themselves as “nationalist,” “unionist,” or “other.” Voting by designation is used to test cross-community agreement—in effect providing a veto to the two political blocs and giving licence to intransigence.

This veto has been used 159 times since 1998, unionists using it about three times as often as nationalists, including preventing same-sex marriage, abortion rights, and welfare reform.

The result of the Belfast Agreement has been to consolidate the two communal political blocs. Despite the historic shifting in the balance of power achieved at the recent election, Sinn Féin did not actually increase its number of seats and only increased its vote by 1 per cent. The DUP lost 7 per cent of its vote, but a unionist party even more intransigent than it, Traditional Unionist Voice, increased its vote by 5 per cent. The designations following the election were unionist 37, nationalist 35, and other 18.

At its 2017 Congress the Communist Party noted: “When the Belfast Agreement was implemented in 1998, the CPI recognised the possibilities it could bring regarding the cessation of paramilitary action and the potential of political struggle that helps to build the unity of the people and of the country. We have always held the view, however, that in the interests of real democracy we need to go beyond the agreement.”

That need for institutional reform has become more apparent since then and was loudly called for at the recent Assembly elections by the party that made most electoral gains, the centre-right cross-community Alliance Party, which designates itself as “other.” It increased its share of the vote by 5 per cent and its number of seats by a third, to 17.

The growth of the Alliance Party vote alongside Sinn Féin’s position as the largest party, and the splits within unionism, suggest a fluidity in the political situation. This provides opportunities in which political, social and economic struggle can be developed in order to build, from below, the unity of the Irish people and of the country—something Sinn Féin have been unable to achieve despite their efforts and the DUP have no interest in.

Throughout Ireland, republicans—inside and outside Sinn Féin—socialists, labour movement activists, campaigners on issues of the environment, women, youth, health, education, housing, peace and international solidarity need to link their struggles. The requirement for an all-Ireland outlook was clearly shown during the Covid pandemic, and the results that can be won by militant action are being taught by the strike wave at present under way in Northern Ireland.

Experiences of unity in struggle will require expression in reformed political institutions in the North. Experiences of unity in struggle must also inform the debate on the political institutions and policies needed to build a new, united Ireland.