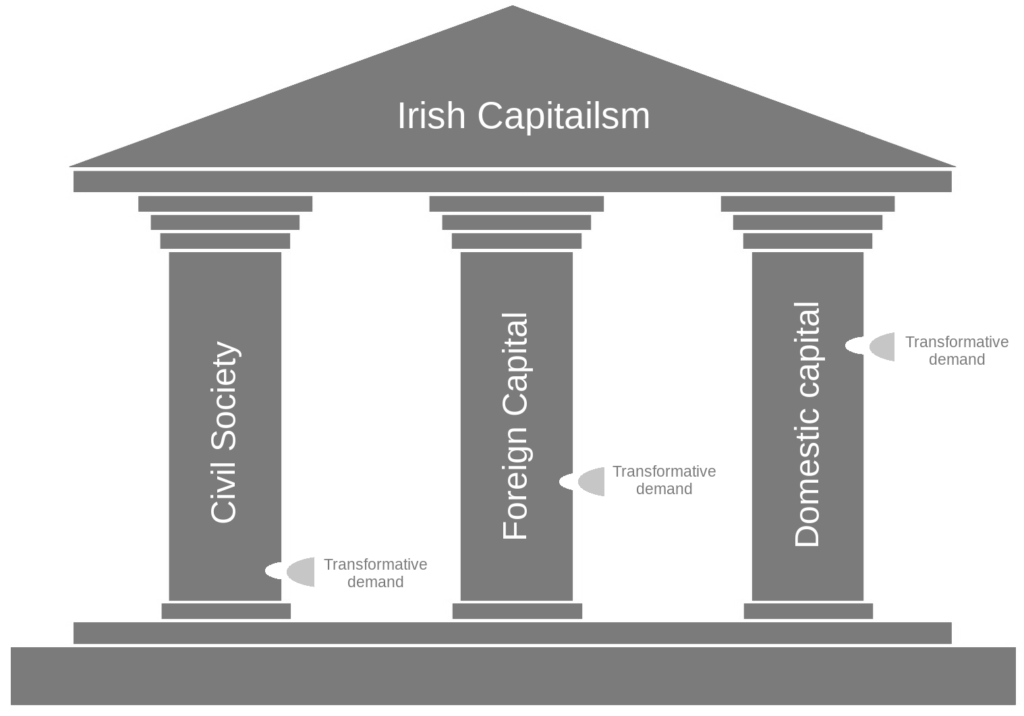

Continuing with the analogy established in the preceding article, we can think of the specific structure of capitalism as resting on three pillars: civil society, foreign capital, and domestic capital.

If we think through this heuristic model we begin to realise the enormity of the task, but conversely we also have a defined and tangible point of focus. This raises the issue of which pillar to focus on; not all pillars are equally stable and there will be, at any moment in time, one area that will offer the best opportunity for us to deepen cracks and fractures by driving a wedge.

Therefore it is a strategic rather than a political question, and we must evaluate the position of class forces in society and the areas of weakness and strength both within our own movement and within the structure of Irish capitalism. These actions are required to make a decision on how best to plan our offensives in the months and years of struggle that lie ahead.

Focus on first pillar

Two of the largest concerns facing the Irish people, according to an Irish Times opinion poll in 2020,¹ are health and housing. These issues are linked with the first pillar: the structure of civil society. Part of the Irish capitalist class’s ability to maintain their hegemonic position in society has been through their successful strategy of dividing and co-opting sections of the working class to align their interests with those of capital. The private provision of both health services and housing has tended to offer a successful example of this, where privileged segments of the working class have been pacified by being provided with a means to purchase their way out of collective social problems wrought by a lack of investment in public health and housing.

As the crises of housing and health continue to unfold and these issues increasingly find common ground because of the pandemic and the intensity of the housing crisis, they present points of potential unity through which the logic of capital accumulation can be counterposed against a “common good” and so challenge the hegemony of the capitalist class.

If the reader considers the issue of housing, the policies of the government not only fail to resolve the crisis but continue to make it worse. Government policy, in other words, serves the interests of investors and landlords, both foreign and domestic; it does not serve the interests of the average citizen who should have affordable access to a home. Housing, therefore, presents a point where we might concentrate a weight of effort in the hope of creating further fractures and opportunities.

Focus on second pillar

The second pillar, foreign capital, raises the issue of the triple lock of imperialism in Ireland theorised by the CPI. The triple-lock concept emphasises that Ireland is dominated by and dependent upon three separate imperialist powers, which have used this country in different ways to pursue their respective interests. These are:

- The United States in the industrial field through our dependence on transnational corporations.

- The European Union in relation to monetary policy, regulation and legal matters, which lock us, like other peripheral countries, into a neoliberal chain of dependence that benefits mostly German capital.

- Britain in the direct occupation through the institution of partition.

As with all models, including the one we are presenting here, we are making an abstraction to help identify the various strands of foreign capital, which are woven into the structure of Irish capitalism. In reality imperialist interests overlap in both complementary and conflicting ways. For example, Britain also exerts economic and legal influence, and its role cannot be reduced to that of partition.

Saying that, we can summarise that these are the primary contradictions presented by each of the three imperialist forces. Each exerts political and economic influence to varying degrees, which in turn has an impact on the political, economic, social and cultural development of Ireland.

If we are to assess how best to attack the second pillar we should consider levels of popular support in relation to each of these imperialist blocs. This can help orient our blows towards the weakest link in the chain, or the most vulnerable cracks.

Examining these three issues separately, recent opinion polls show that Irish support for EU membership is still high, at 84 per cent,² which would indicate that at this particular juncture a prolonged campaign to highlight the detrimental aspects of EU membership would require much effort with little hope of tangible results.

In relation to the United States, during the height of the Great Recession two-thirds of the people surveyed did not wish to see an increase in the rate of corporation tax,³ and current debates over increasing corporation tax to 15 per cent have not garnered widespread public support. However, with international pressure to introduce a minimum rate of global corporation tax, this may offer opportunities in the future.

The weakest link in the chain can be seen in the North. The Irish Independent/Kantar poll found that in the Republic two in three polled, 67 per cent, supported a united Ireland, compared with 16 per cent who were opposed. In Northern Ireland this poll suggested that while 35 per cent of adults were in favour of a united Ireland, 43 per cent were against—although, significantly, one in five did not express an opinion.

Despite that difference of opinion on a united Ireland between North and South, the survey suggests that seven out of ten voters—in both jurisdictions—wanted a reunification referendum within five years.⁴

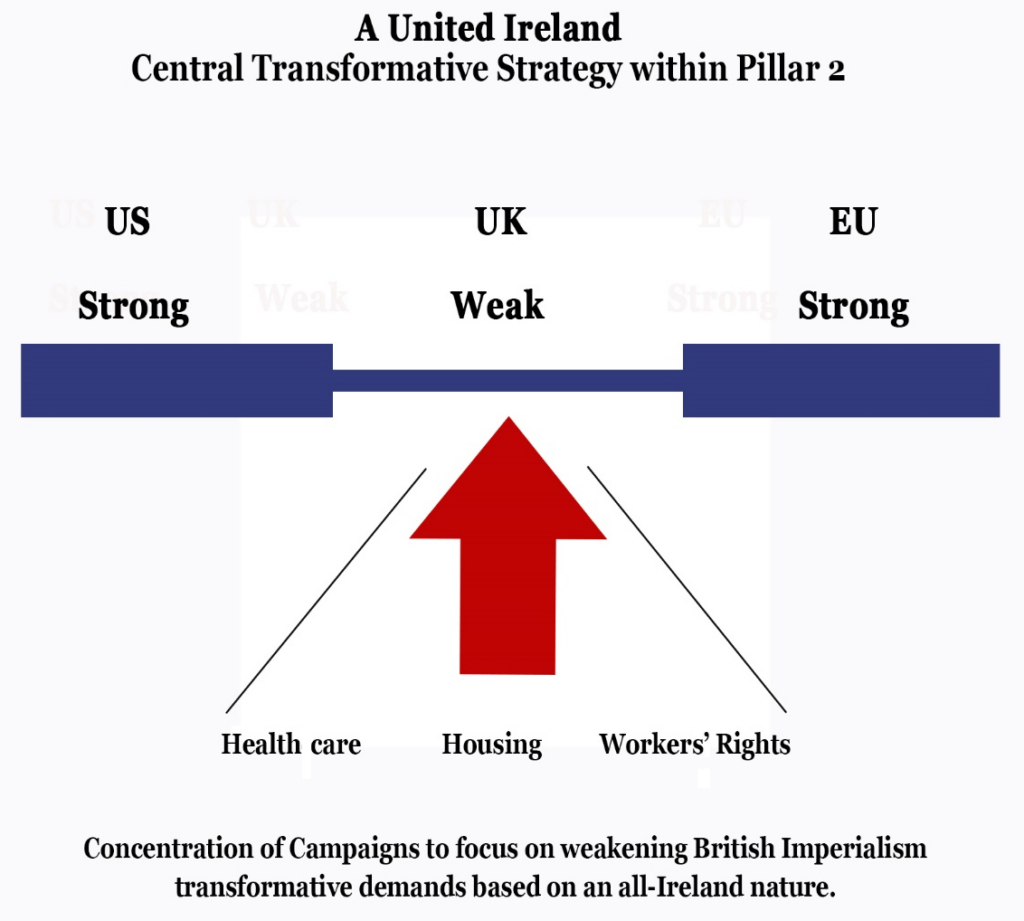

There is clear support within the next five years for a border poll to unite Ireland, which would have an objective effect of challenging British imperialism. We can clearly identify this as a weak spot on which to focus our weight of effort.

The key to this is not the border poll itself, as if we are under the delusion that the path to Irish unity is is a neo-Redmondite strategy of pressuring London and Dublin for a referendum. Rather the border poll can act as a focal point that enables us to co-ordinate a host of transformative demands into a powerful wedge.

The border poll is a point of focus to facilitate calls for transformative demands that lay the material foundations for a unified Ireland. Such transformative demands may include all-Ireland solutions to areas of weakness in the other pillars, such as an all-Ireland public health system and an all-Ireland public housing scheme. This has the potential to seriously undermine a central pillar, which may open up new fractures and points of weakness for the future.

Fig. 2 offers a visual representation of how we can think about co-ordinating a series of interrelated transformative demands into a single campaign. Such a campaign would be directed upon a single point of weakness. The broad campaign (a united Ireland) can act as a central goal, and supporting campaigns could be oriented towards that central goal.

This type of strategy has central, supporting and reserve roles, hence being able to apply a weight of effort against an area of weakness, giving it the greatest chance of success. In the broader context, the end goal isn’t a united Ireland, but a united Ireland will help to further weaken the existing structure of Irish capitalism and open new opportunities for socialist interventions.

Focus on third pillar

In regard to the third pillar, the structure of indigenous capital, domestic capital depends in a large part on the role of international capital within the Irish economy. To this extent they are separate entities but it is difficult to convey the relationship in fig. 1. Areas of vulnerability that can be central to weakening this pillar can be found in relation to improving workers’ rights and increasing wages and levels of labour organisation, with particular emphasis on the negative effects that the Industrial Relations Act (1990) has had on workers.

In the light of recent events on the global taxation front, we might also consider the role of building support for long-neglected domestic industrial policy based on public ownership of infrastructure and means of production. Both these examples of structural weakness in domestic capitalism could also include an all-Ireland element, reinforcing the weight of effort in the offensive against the other pillars.

Weakening the structure

This article is simply outlining a number of possible focal points towards which to funnel our energy and resources. The breaking of British imperialism, the abolition of the Industrial Relations Act and demands for public housing and health on an all-Ireland basis all present potential opportunities as transformative demands, each of which has the potential to be interlinked and reinforcing.

These transformative demands can act as wedges that can be hammered constantly and repeatedly in order to create bigger fissures than would otherwise be possible. Pinpointing these strategic areas opens three major fronts on the three pillars for a conscious, broad working-class offensive against capitalism in Ireland.

These actions in themselves will not knock the capitalist structure down; it is a bit enthusiastic to assume that such a feat is possible even for the Irish left in its present state, much less the CPI. However, it would begin the process of creating new points of weakness where further cracks will emerge, forcing us to reconsider our focal points and assess where new weights of effort can be applied to continually and consciously undermine the strength and integrity of capitalism in Ireland. As has been said from the outset, the most important thing is pinpointing where we concentrate our blows.

The next logical step for the CPI and the broader anti-imperialist movement that is serious about transformative and revolutionary change is to set short, medium and long-term goals to meet these strategic objectives. This is exactly what the CPI intends doing at its 26th National Congress next year. This has to be met with a serious attempt at collaboration with allies who are willing to build a broad front, where each party or group can maintain its autonomy but remains committed to working towards the fulfilment of shared strategic objectives derived from an agreed focal point.

For such co-operation to be possible there needs to be agreement on a minimum programme with maximum support. For example, a minimum requirement might be support for a united Ireland, an all-Ireland public health service, an all-Ireland public housing scheme, and an all-Ireland campaign to abolish anti-union legislation—all points that organisations that proclaim some support for socialism should consider uncontroversial. Insisting on a maximum programme, which would necessarily lead to minimum support, is infantile and will lead nowhere. One can objectively work towards the establishment of a 32-county socialist republic without demanding that it is a necessary precondition for all parties that work with us on point issues to sign up to the same goal.

This may be one of the most difficult aspects in trying to form a broad strategy and build a coalition, as electoral politics and rampant opportunism have historically hampered collaboration on the Irish left. Without a minimum programme agreed upon by the broadest spectrum of left forces in a disciplined but unified front, it is hard to see how we will move from spontaneous to conscious blows against capitalism. In the years ahead we hope that the CPI can move towards playing a leading role in addressing this issue and engage in mutually beneficial working relationships with all fair-minded progressive forces.

- Pat Leahy, “Irish Times Poll: Health and housing most important issues for voters,” Irish Times, 5 February 2020 (tinyurl.com/um75u95j).

- Irish Council for the European Movement, “Ireland and the EU Poll” (tinyurl.com/zwdawea5).

- Conor Ryan, “Leave taxes alone and cut spending, warn public,” Irish Examiner, 4 December 2010 (tinyurl.com/3kscr6zt).

- Fionnán Sheahan, “Majority favour a united Ireland, but just 22pc would pay for it,” Irish Independent, 1 May 2021 (tinyurl.com/hzykmu6e).