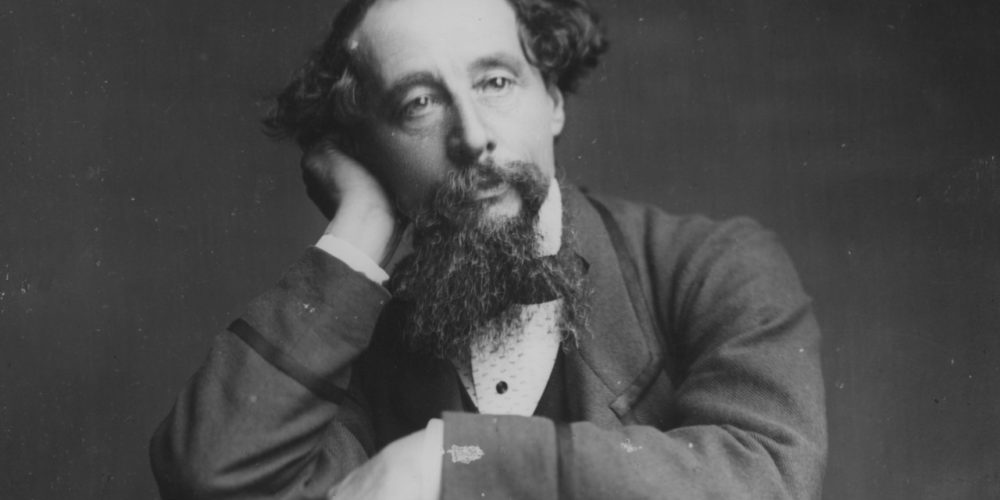

Charles Dickens was born in 1812 into the impoverished petty bourgeoisie. His father was imprisoned for debt, and financial circumstances forced the young Charles to leave school at the age of twelve and to work a ten-hour day in a blacking (shoe polish) factory.

The adult Dickens’s first jobs were as a parliamentary reporter for radical magazines, and so he moved in radical circles. He was also instrumental in organising a strike by the reporters of the True Sun and successfully acted as their spokesperson. As his love of writing developed, he began to earn his living by selling his books and writing.

Dickens was born into the rapidly accelerating period of the Industrial Revolution, which powered the transition of British capitalism into its imperialist phase. His writing coincided with the fortunes of the Chartist movement and on to the upheaval of 1848–49 and then the triumph of European reaction in 1850, the collapse of the English socialist movement under Robert Owen, and then its revival under the First International in 1864.

Dickens always regarded himself as one of the common people, sympathising with them and exposing injustice against them. This made him lastingly popular with the ordinary folk. His stance that the poor should be treated as human beings was in itself a revolutionary demand.

Taking this stance led Dickens to develop a new type of novel. His books take the focus away from characters in the wealthy classes and towards the lives of ordinary, mostly urban children, men and women, who grapple with everyday challenges. With his strong sense of individuality he made these people extraordinarily vivid. He shows his readers the darker side of society in the first great industrialised metropolis in the world. His most interesting and valuable characters are usually people from the lower social classes.

In 1842 Dickens travelled to the United States as a committed supporter of American independence, seeking to find the democracy of his dreams. Not only was he disappointed in this but the existence of slavery and its enthusiastic defence by many of those he met outraged him. After his return he wrote American Notes for General Circulation (1842), which strongly criticised American society and its values, especially slavery and violence, as well as its extreme individualism.

In his novel Martin Chuzzlewit, published shortly afterwards, he also described the conflict he experienced between expectations and reality in the United States.

Until his visit to America, Dickens’s viewpoint was directed exclusively towards southern England, while the main impulse for Chartism came from the industrial Midlands and the North. Not surprisingly, Dickens’s radicalism in his earlier novels was more moderate and at first represented incidental ills; but as his writing developed, the entire social system that he depicts increasingly proves to be deeply rotten and unreformable.

Great Expectations

By way of example, let us turn briefly to one of Dickens’s later novels, Great Expectations (1860–61), in which the expectations of the title are those of a boy from the working class and are attached to the hope for a wealthy patroness’s good will. The novel describes Pip’s development, and the shock of disillusionment.

In this book there is no hope that conditions could be put right by the benevolence of the ruling class. Instead it is the outcast Magwitch, cheated, exploited, and brutalised by the law, who shows gratitude and generosity to Pip. Just as the bourgeoisie owes its wealth to the exploitation of the working classes, so Pip owes his wealth to Magwitch—and Pip is just as ungrateful as the bourgeoisie.

Dickens’s depiction of the characters of two lawyers, Jaggers and his employee Wemmick, is also noteworthy. They are ruthless in their working lives but lead a completely different, compassionate private life, showing that success in business is achieved only at the expense of one’s own humanity. Jaggers always washes his hands following a particularly dirty job. Pip also changes during the time of his “expectations,” at the expense of his humanity, painfully expressed in his shameful treatment of Joe Gargery and Biddy.

The novel shows the folly of indulging in illusion. Dickens’s original ending underlined Pip’s complete break with his aspirations for social advancement and his insight into the heartlessness of “better” society. However, under pressure he changed the ending in favour of a happier outcome. George Bernard Shaw commented that Dickens’s original conclusion was the true happy ending. The logic of the novel contradicts the changed ending. Its most admirable characters are the blacksmith Joe Gargery and the teacher Biddy, Gargery’s second wife. Pip himself, as the main character, begins and ends as a working person.

Dickens has had a great and continuing influence on subsequent writers. For example, in Robert Tressell’s Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists not only does Tressell expand on Dickens’s focus by depicting a panorama of working-class people but he is also clearly steeped in the Dickensian tradition in his use of names or motifs that contain the power of social generalisation.

In this sense, Dickens’s increasingly fierce and pointed satires help prepare the ground for working-class literature.