In the early 1950s American companies wanted to invest in Ireland so that they could expand into the European market; and Irish corporation tax policy was adapted for them.

In 1956 export profits tax relief was introduced. Exports of manufactured goods were zero-rated (no tax); so American companies that exported all their output paid no tax on their profits.

This rate of tax applied to all foreign companies, and many European companies set up subsidiaries here to avail of it before Ireland joined the EEC, as it was then. Ireland joined to give American transnationals tariff-free access to the EEC countries’ markets, and agreed to phase out the zero-rate corporation tax.

In 1980 a 10 per cent tax on manufacturing activity was introduced, with EU approval. In 1987 a 10 per cent tax on financial services was introduced, again with EU approval. In 1996 the EU withdrew its approval for these tax incentives, and they were phased out between 1996 and 2010.

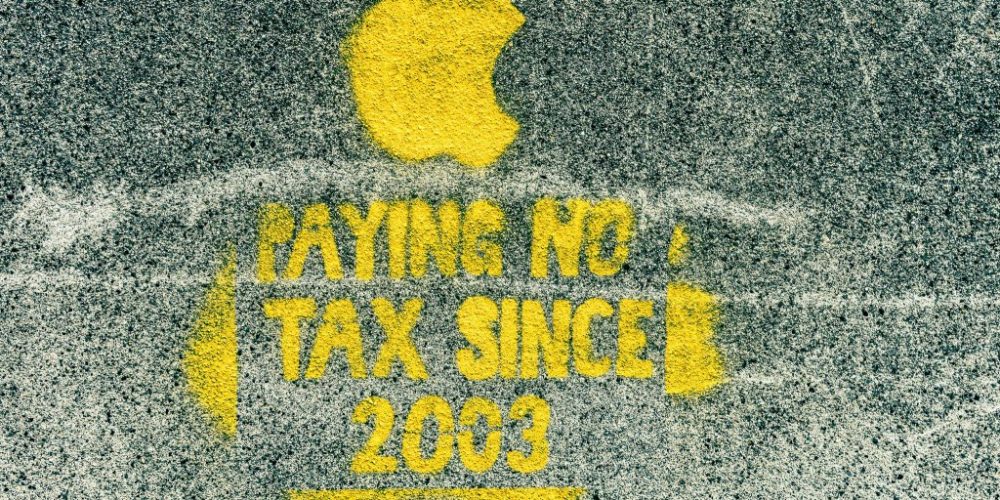

Between 1996 and 2003 there was a phased reduction in the general rate of corporation tax, from 32 per cent to 12½ per cent to apply equally to all corporate taxpayers on trading income, and to 25 per cent on non-trading income.

The present rate of corporation tax is 38.9 per cent (soon to become 20 per cent) in the United States, 34 per cent in France, 30 per cent in Germany, 19 per cent in Britain, and 12½ per cent in Ireland. In a tax haven like Jersey the rate of corporation tax is 0 per cent.

So, if a transnational can shift its profits from, say, France to Ireland, it reduces the tax rate from 34 per cent to 12½ per cent. And they have been doing this since the 1950s.

The savings can be immense, especially if an American transnational operating from Ireland can reduce its rate of corporation tax to about 0 per cent, as Apple has done in the €13 billion case taken by the EU Commission. If €13 billion is the tax you pay at 12½ per cent, then the profits involved would be over €100 billion. As the corporation is an American one, it would pay €38.9 billion tax on these profits if they were declared in America. So there is a saving of €25.9 billion by declaring in Ireland and not declaring in the United States. That is, if they paid the €13 billion to the Irish government. As they did not, the saving was €38.9 billion.

The people who gain from all this are the shareholders of transnational companies; because if the companies pay no corporation tax, then shareholders pay no corporation tax.

If shareholders receive dividends (income) from companies each year, they have to declare them to the tax inspector. The method of declaring the dividends is self-assessment. Dividends, paid out of profits after corporation tax, are also subject to income tax.

What’s left after dividends are taken from profits and after corporation tax is called retained earnings, and these are ploughed back into the company. They cause the share price to rise, but again the method of collection is self-assessment.

But there is a loophole. If shareholders buy their shares on the internet, national governments will not know about their ownership of shares. The shareholders will be able to avoid declaring their dividends or capital gains. So they could end up paying no corporation tax, no tax on their dividends, and no tax on their capital gains—no tax at all.

Because of this the Irish government has introduced a withholding tax on dividends of 20 per cent. This applies only to resident Irish companies. If a company that shareholders invested in is abroad, it is unlikely that the Government will get any tax from the shareholders.

This excludes the multi-millionaire shareholders who are resident abroad for tax purposes. They pay no tax in Ireland, even though they wield a lot of influence here.

Compare this 0 per cent tax with the current PAYE tax rate of 49 per cent for people earning over €33,800 in 2017, or on the annual average earnings of €37,419 in the third quarter of 2017. These people pay 49 per cent on each extra euro they earn.

Compare the shareholders’ 0 per cent tax with the current PAYE rate (26½ per cent) for a person working 40 hours a week on the minimum wage of €9.25 per hour. When tax and USC and PRSI are taken into account, the person on the minimum wage pays 26½ per cent on each extra euro he or she earns.

It surely is a nice country to be a shareholder in!