The most famous, fabled and fêted Irish filí (poets) are male. The reasons lie clearly in patriarchal class society. All the more reason for us to seek out the female representatives of a skill that in the old Irish days was associated with prophesying or “seeing,” in fact the Irish word file derives from just this meaning.

The oldest piece of writing that has come down to us, albeit through the lens of Early Christian monks, celebrates powerful women, including just such a prophetess-poet, Fedelm. This profession was largely oral, initially in a pre-literate society, and survived for a long time in storytelling and so on. Some types of poetic expression were the reserve predominantly of women. Most notably among these, perhaps, is a caoineadh or lament. Eibhlín Dhubh Ní Chonaill’s “Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire,” (Lament for Art Ó Laoghaire), spoken in 1773, is one of the greatest laments in Irish literature.

In this lament Eibhlín Dhubh describes the circumstances surrounding the murder of her husband, Art, in Carraig an Ime, Co. Cork, at the behest of a planter, Abraham Morris.

At the same time the lament speaks on behalf of the oppressed Catholic population of Ireland, suffering under colonial rule. Specifically, this is about the rebellion against the Penal Laws, which prohibited, among other things, education for Catholic children, and restricting the right to property—for example owning a horse worth more than five pounds.

Morris outlawed Art Ó Laoghaire for refusing to sell him for five pounds a horse that Art had brought back from his service in the Austro-Hungarian army. He decreed that Ó Laoghaire could consequently be shot on sight.

Art and Eibhlín came from important Irish families. The earls had fled from Ireland to the European continent, consolidating the complete collapse of the old order. Part of the surviving Catholic nobility, Art was educated on the Continent, and served as a hussar.

The Lament is divided into five parts. The first part was probably spoken by Eibhlín over the body of her husband in Carraig an Ime, beginning with a short account of how the lovers met, eloped, and married.

My steadfast love!

When I saw you one day

by the market-house gable

my eye gave a look

my heart shone out

I fled with you far

from friends and home

Eibhlín repeatedly addresses Art as friend and partner, as an equal. Here she describes the awe and fear that Art instilled in the English by his imposing figure and defying the Penal Laws. He carried a valuable sword, wore splendid clothes ,and rode his white-faced steed.

My steadfast friend!

it comes to my mind

that fine Spring day

how well your hat looked

with the drawn gold band,

the sword silver-hilted

your fine brave hand

. . .

You were set to ride

your slim white-faced steed

and Saxons saluted

down to the ground,

not from good will

but by dint of fear

—though you died at their hands,

my soul’s beloved . . .

She also evokes their happy home life and Art’s love for his sons.

Then she speaks of the moment when Art’s death became clear to her, when his horse returned riderless to their homestead. Eibhlín’s determination and courage increases, and she leaps into the saddle and gallops to the scene, where she finds Art’s lifeless body:

to find you there dead

by a low furze-bush

with no Pope or bishop

or clergy or priest

to read a psalm over you

but a spent old woman

who spread her cloak corner

where your blood streamed from you,

and I didn’t stop to clean it

but drank it from my palms.

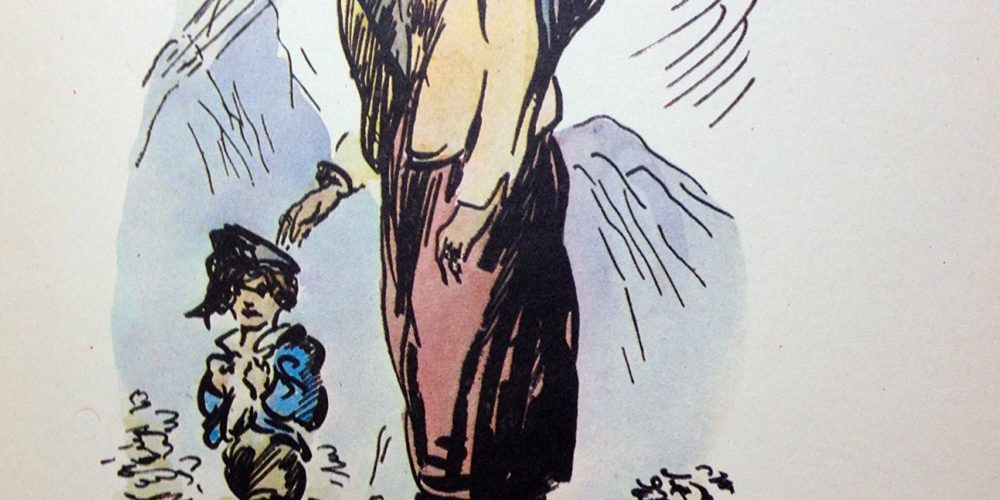

No-one is present, other than this old Mother Ireland. Her identity is evident in that she uses a traditional cloak. It is also significant that no Catholic clergy were present. Eibhlín is left alone with this woman.

It is a desolate picture of the state of the country and its forgotten loyalties. Remarkably, in all this lament there is no hope for life after death; one might even say that the absent clergy at the scene have disqualified it from a role in the liberation of the country. Eibhlín can only rely on herself alone—supported by old Mother Ireland.

In the second part, a dispute between Art’s sister and Eibhlín takes place, in which her sister-in-law accuses Eibhlín of having been in bed when she came to the farm from Cork. This may well be a commentary on the discord between the two noble families and, in a wider context, on the disintegration of the vanishing Gaelic order.

As the body is prepared for burial, Eibhlín utters her curse on Morris.

Ruin and bad cess to you,

ugly traitor Morris,

who took the man of my house

and father of my young ones

—a pair walking the house

and the third in my womb,

and I doubt that I’ll bear it.

Then, images from nature suggest that Art was the true ruler of the country, even if the population has forgotten this.

Take the narrow road eastward

where the bushes bend before you

and the stream will narrow for you

and men and women will bow

if they have their proper manners

—as I doubt they have at present . . .

Into every part of this lament is written Eibhlín’s resistance against foreign rule and the oppression of her people. This connects her very closely with Art.

Returning to the murder, Eibhlín explains her resolve to avenge it. She will use every avenue to obtain justice: She will sell her belongings:

but I’ll spend it on the law;

that I’ll go across the ocean

to argue with the King,

and if he won’t pay attention

that I’ll come back again

to the black-blooded savage

that took my treasure.

If the legal paths fail, Eibhlín is ready to avenge Art herself, the man who represented Ireland’s Gaelic order. Increasingly, Eibhlín develops into the independent woman who will determine her life and, by implication, stand up for her people.

In the last, fifth part Eibhlín’s grain and livestock are thriving despite her great grief. She has taken up Art’s legacy. She will run the farm, raise the children, and avenge Art. Contrary to the expectations in seventeenth and eighteenth-century aisling poetry, in which a female figure awaits a male saviour, Eibhlín takes this fate into her own hands, following in the tradition of the strong Gaelic women, and will free Ireland from foreign rule.