The Illusion of Competition: Why Capitalism Breeds Inefficiency

Capitalism, in its idealised form, is built upon the foundation of perfect competition. Orthodox economic models envision a utopia where countless small firms vie for market share, prices reflect the marginal cost of production, and resources flow seamlessly to their most efficient uses. But this vision is just that—a vision, untethered from the reality of modern capitalist economies. Instead of competitive markets, what we encounter are markets dominated by monopolies or oligopolies, leaving behind inefficiency and inequality.

The Myth of Perfect Competition

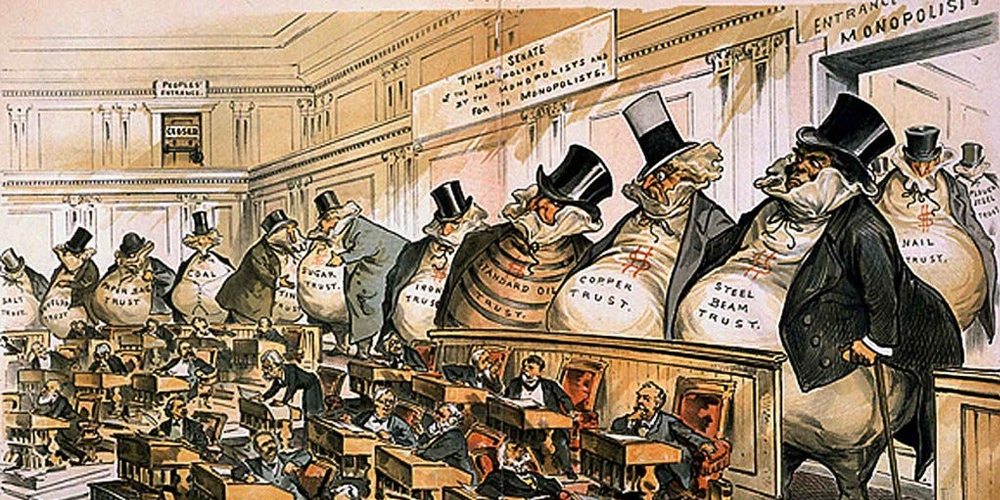

Perfect competition, as described in classical economics, requires several stringent conditions: a large number of buyers and sellers, homogeneous products, perfect information, and no barriers to entry or exit. These conditions are seldom, if ever, met in real-world markets. Take any industry—technology, pharmaceuticals, energy, food, communication or transport—and you will find the dominance of a handful of giant corporations. These firms wield immense market power, dictating prices, stifling competition, and accumulating profits at the expense of consumers and smaller players.

Consider the tech sector. Companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft operate in markets where barriers to entry are virtually insurmountable due to economies of scale, network effects, and intellectual property protections. These firms—far from being price takers as assumed in perfect competition—are price makers. They set prices strategically to maximise profits, often at levels that extract exorbitant rents from consumers while marginalising smaller competitors. Such market structures bear a closer resemblance to monopoly or oligopoly markets, where the allocation of resources is distorted, and inefficiency thrives.

Monopoly Markets and Capitalist Inefficiency

Orthodox economic theory itself acknowledges the inefficiency of monopoly markets. In a monopoly, the firm restricts output to raise prices above the marginal cost of production, generating abnormal profits while leaving a deadweight loss in its wake. This deadweight loss represents unmet needs and wasted potential—goods and services that could have been produced and consumed if prices were lower.

In sectors like energy or waste management, a few private firms often dominate, extracting significant profits from providing essential services. These profits come directly from customers who pay higher prices than they would in a truly competitive market. For example, energy firms charge prices that not only cover costs but also generate substantial profits for shareholders. These profits do not benefit the public; instead, they are concentrated in the hands of a few, exacerbating inequality and perpetuating inefficiency.

Public Monopolies as a Solution

The inefficiency of private monopolies poses an important question: what alternative can better serve societal needs? The answer lies in state ownership and public monopolies. Unlike private firms, which are beholden to profit maximisation, public monopolies can prioritise accessibility, affordability, and equity. By leveraging their position as price makers, public monopolies can set prices at levels that benefit the majority, rather than a privileged few.

Take public utilities, for instance. A private energy company will set prices at a profit-maximising point, often excluding lower-income households from access to essential services. A public energy provider, on the other hand, can set prices to ensure universal access, reflecting the true social cost and benefit of energy provision. Additionally, profits from a public monopoly can be reinvested into better infrastructure, ensuring long-term efficiency and reliability. Alternatively, these profits can be used to reduce prices for consumers or to cross-subsidise other critical sectors such as healthcare or education.

In the waste management sector, for example, a public monopoly could reinvest profits into advanced recycling technologies or subsidise waste disposal services in underserved areas. This approach eliminates inefficiencies and ensures that essential services are delivered equitably.

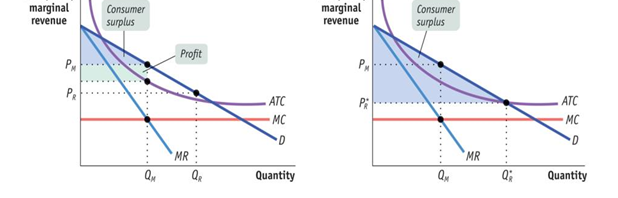

In economic terms, the inefficiency of private monopolies is illustrated by the classic monopoly diagram. A monopolist restricts output (Qm) to raise prices (Pm) above marginal cost (MC), creating a deadweight loss (DWL) between the socially optimal output (Qr) and the monopolist’s chosen output. A public monopoly, however, can set prices at the socially optimal level (Pr), expanding output to meet societal demand without the need for profit maximisation.

Below are diagrams illustrating these concepts:

- Private Monopoly Inefficiency:

- A graph showing the monopolist’s profit-maximising output (Qm) and price (Pm), with deadweight loss (DWL).

- Public Monopoly Efficiency:

- A graph showing the socially optimal price (Pr) and output (Qr), with no deadweight loss, emphasising the benefits of public ownership.

The Path Forward

The capitalist illusion of perfect competition has obscured the reality of monopoly-dominated markets for too long. The inefficiencies of these markets are not an aberration but a structural feature of capitalism itself. By embracing public monopolies in key industries—transport, energy, utilities, health and housing—we can reclaim these sectors for the public good. We don’t need four or five companies operating to extract profits for its shareholders, all delivering to greater and lesser degrees the same service, whether that be electricity/gas, wifi/broadband or waste disposal to a household. We don’t need private toll companies operating our motorway systems to ensure healthy profits for its owners, we don’t need construction companies building smaller and smaller houses in new housing estates at prices beyond affordability of working people.

It may seem simple, but often the simplest idea is the correct one, where a state-owned company can operate close to a monopoly position and can set prices and allocate resources in a way that serves everyone, rather than privileging the few. We don’t need to convince all people that all sectors and all industries at once need to publicly owned, we just need to convince enough people that public ownership in strategic areas of the economy will benefit them personally, through lower prices, and socially through much more equitable means of production and distribution.

In the recent general election, there was a choice between political representation, but no choice in economic alternatives, creating merely the illusion of potential change through democratic means. The fact that turnout was so low demonstrates that people are either disillusioned with the current political and economic status quo or have been left out of the democratic process through economic emigration. The economic alternative of public ownership in key sectors of the economy is what working people must demand. When a political party is strong enough to champion that type of manifesto at a general election, then there will be a real existing alternative political opposition, separating them from the political cartel that currently operates in Ireland.