The trajectory of the global capitalist economy reveals a deep and persistent malaise. Since the Great Recession of 2008-2009, G7 economies have failed to regain their former dynamism. The acute yet temporary recession triggered by the global pandemic has only exacerbated this long-term trend. Across the G7, metrics for business investment, output, living standards, and labour productivity show stagnation or negligible growth, falling well below the pre-2008 trajectory. The current epoch of capitalist development marks a departure from the traditional cyclical crises of the past. Unlike the classical U-shaped or W-shaped recessions of earlier eras, the post-crisis recovery now consistently fails to restore prior growth trends. Economic contractions of 1-2% no longer give way to pre-crisis growth rates but instead usher in prolonged stagnation.

This dynamic has defined the aftermath of both the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic-induced slump of 2020, particularly in the EU, Eurozone, and Japan. The United States, while outperforming its G7 peers, is barely achieving growth at 2%, while the rest hover around 1% or stagnate entirely, as in the cases of Japan and Canada. Worker productivity continues its long-term decline, reinforcing the broader malaise. The 2020s thus stand as one of the weakest periods for global capitalist expansion since the early 1980s.

Ireland’s performance, when stripped of distortions from imported intellectual property and aircraft leasing, reveals a tepid reality. Modified Domestic Demand (MDD) measures show stagnation in per capita terms since 2007. The North’s trajectory, meanwhile, aligns with the broader stagnation evident in other advanced economies.

Compounding this stagnation is the waning of innovation. Total factor productivity, a measure of efficiency in combining labour and capital, indicates declining dynamism in the heartlands of capitalism. Without significant breakthroughs in productivity, there is little impetus for increased business investment. Across the G7, fixed investment as a share of GDP remains flat, oscillating between 10% and 15%.

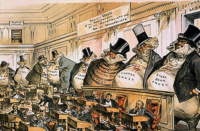

For Marxist economists, this reflects a deeper structural issue: the secular decline in the rate of profit. Evidence suggests that profit rates across the G7 have fallen by roughly 40% over the past half-century. This chronic fall in profitability undermines the very engine of capitalist accumulation, leading to sluggish investment, diminished growth, and speculative forays into financial markets. The expanding role of debt – with corporate borrowing soaring even as profits falter – underscores capital’s desperate search for returns. Global debt levels have ballooned to over 300% of world GDP, revealing the unsustainable contradictions of the current order.

In theory, capitalism’s crises serve as moments of “creative destruction,” where unprofitable capitals are liquidated, paving the way for renewed accumulation. Yet, the contradictory role of the capitalist state – tasked with both sustaining accumulation and ensuring social stability – obstructs this purgation. Political pressures often lead states to bail out failing enterprises, producing a proliferation of “zombie companies” that drain resources while avoiding destruction. These half-measures reflect the ruling class’s inability to stomach the full force of crisis without risking social unrest.

Technological innovation is often posited as a potential escape route. Hopes are pinned on automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence, yet the barriers to their widespread adoption remain significant. Low profitability and high debt burdens inhibit the capacity of capital to invest in these technologies at scale. Moreover, history demonstrates that transformative innovations typically take decades to diffuse throughout the economy. In the interim, capital may resort to more exploitative labour practices, squeezing value from an increasingly precarious workforce rather than investing in long-term productivity gains.

Another potential outlet for stagnating capital lies in militarisation and war. Historically, large-scale conflicts have destroyed capital values and restructured economies, offering a grim reset for accumulation. Today, the G7’s declining share of global trade reflects the rise of China as a major competitor. Should inter-imperialist rivalry escalate into open conflict, the contours of global capitalism would depend heavily on US strategy. However, it remains uncertain whether the U.S. can achieve its geopolitical aims through alternative means, or if the contradictions of its declining hegemony will force a turn to war.

In sum, capitalism in 2025 – and in the immediate years beyond – faces a landscape marked by stagnation, declining profitability, and deep systemic contradictions. The prospects for renewed dynamism appear slim, with the forces of creative destruction constrained by state intervention, the limits of technological adoption, and perhaps the shadow of geopolitical conflict.