In the past few months, two important contributions to Irish sports history hit the shelves of bookshops around the country. Labelling these books as Irish sports history is potentially reductive, as both authors make it very clear that the history they write is a shadow of what we would call general history, that of the Irish state, Irish people, class struggle, and struggle for national liberation.

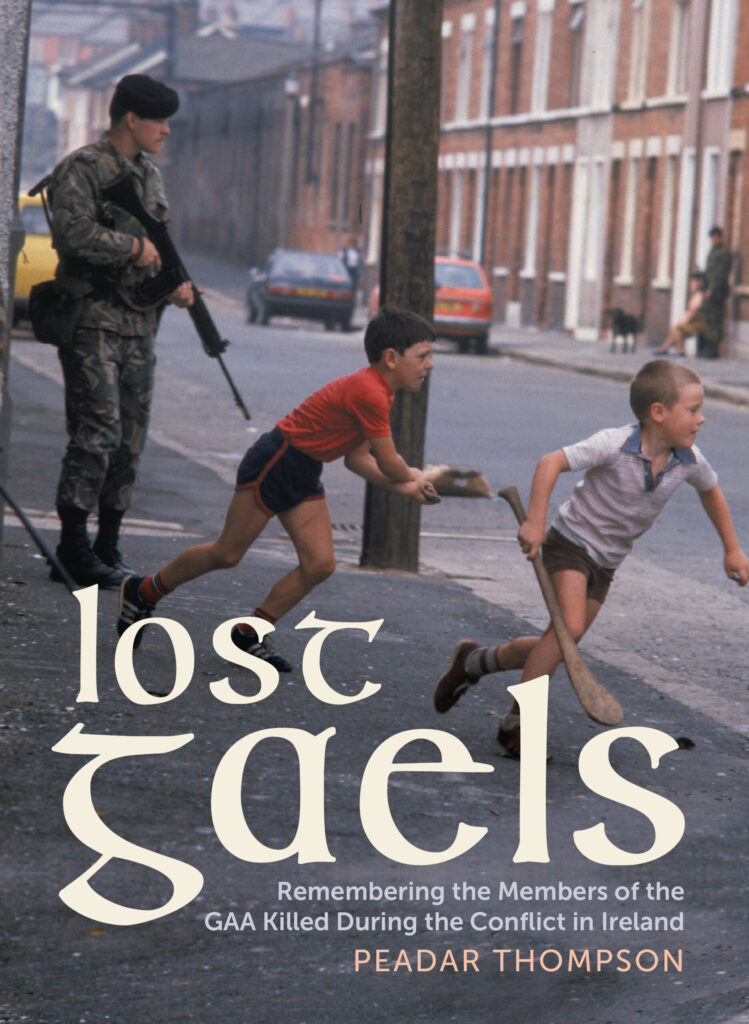

Lost Gaels: Remembering the Members of the GAA Killed During the Conflict in Ireland is Peadar Thompson’s comprehensive oral history project collecting stories from family members and friends of GAA members killed from the 1970s up to the 21st century. For every one of the “Lost Gaels” for whom he could collect information from friends and family through extensive interviews, Thompson wrote an elaborate biography. Therein, he focuses on their everyday lives, weaving the story of their GAA club activity with that of their personal and social life, finally reaching the point of their violent death and the memory left behind. The circumstances of their death and the perpetrators are not in focus, as Mark Thompson from Relatives for Justice explicitly spells out: it’s about an grá for the GAA they all had. Illustrated with photos and the crests of their GAA clubs, these heartfelt profiles are uniform in form, but very diverse in content and focus: this reflects the wide spectrum of people Thompson wrote about, but also the wide spectrum of people he spoke to, gathering material for the book.

While the name of Aidan McAnespie is probably the first that comes to mind when GAA is mentioned in context of the conflict and British occupation of the North of Ireland, The Lost Gaels adds many other names. Thompson was able to write detailed accounts for 92 people and listed more names at the end of the book, with the total number exceeding 150. Many of the stories might be known to the reader – such as that of Máire Drumm, Kevin Lynch, or Kieran Doherty – but the GAA angle provides a new way of contextualising these lives. There are famous stories Thompson was not able to include in the book, but he records the names diligently, so on the last pages of the book we find, for example, the names of Frank Stagg, Raymond McCreesh and Joe McDonnell. The chronologically ordered life stories take the reader through the decades, towns and villages of Ireland, and through all the phases of struggle.

Diligent readers will build their own understanding of the demographics organised in the GAA, its relationship with Ireland and the Irish people, as well as the complicated tensions between GAA members and the GAA itself. Again, this is where GAA shadows the nation in its dynamics and complexity. A selection of essays included in this volume helps the reader navigate these complexities, understand the contradictions, and benefit from historical, analytical hindsight. Particularly insightful is the contribution of Tommy McKearney titled “The hunger strikes and the GAA”: McKearney offers solid analysis with the authority of a well-informed witness to these times. McKearney’s contributions to this volume do not end here: three of his brothers, and his uncle number amongst the Lost Gaels, and Tommy’s recollections are an important part of their stories.

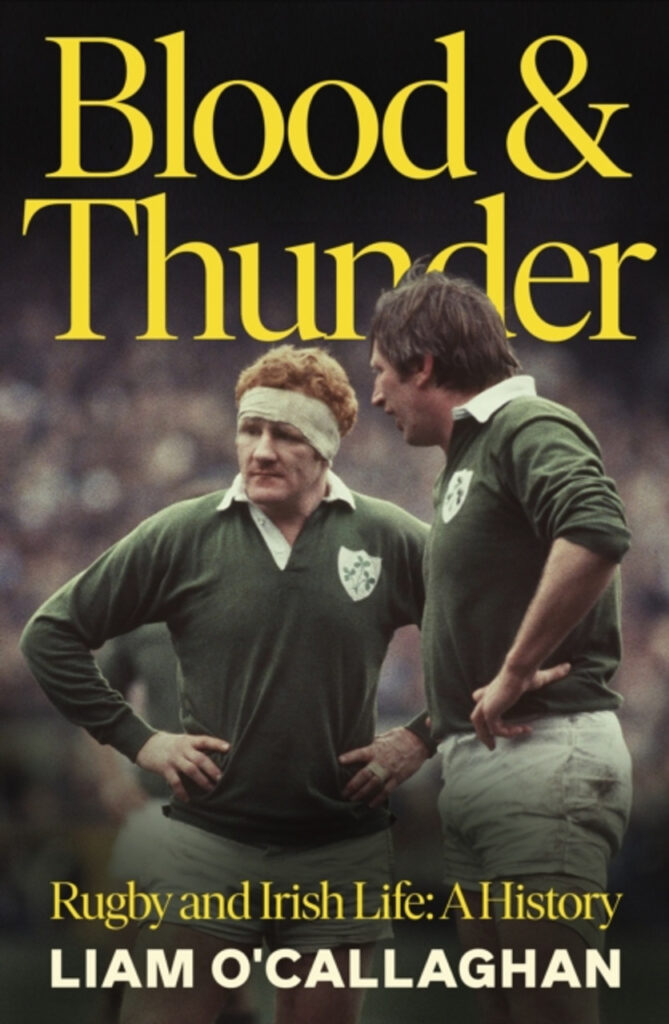

The second book joining Thompson’s on the new arrivals shelf is Liam O’Callaghan’s Blood & Thunder. Subtitled “Rugby and Irish Life: A History”, O’Callaghan’s book takes the reader through the story of rugby in Ireland, which again unavoidably becomes the story of Ireland through the last century and a half. The author recognises how the introduction, development, and success of rugby are linked to the Irish society, and that rugby has been a part of that societal change as well.

Introduced to schools in Britain and Ireland as a game of rules, discipline, and training, rugby in the 19th century is, unsurprisingly, a project of a certain demographic and class. Out of the first 100 players capped for Ireland, writes O’Callaghan, only two were Catholics (one of which, Thomas St. George McCarthy, would become one of the founding members of the GAA). Even looking into the case of those two outliers shows the class nature and institutional framing of rugby. Trinity College was the sole focal point of rugby in its beginnings in Ireland. A while later, Catholic schools would adopt rugby and start competing. Even then, the religious distinction obscures the demographic trend: the rising Catholic class was the one with capital, and which had access to these schools.

O’Callaghan goes through the distinct phases in history of rugby in Ireland: the formation of GAA and antagonism, the First World War and its death toll in the Irish rugby community, partition and the Irish Free State, the conflict in the North of Ireland, the anti-apartheid movement and its effect on international rugby, the professionalisation of rugby, then gender and health challenges in rugby. Through most of the book, the all-Ireland nature of the organisation of Irish rugby is a recurring source of contradictions and challenges, as well as fresh perspectives. This is where many readers will find a chance to challenge or reinforce their grievances with the symbolic layer of Irish rugby, from its flag to “Ireland’s Call”.

What caught my attention reading O’Callaghan’s account of rugby history, especially in the pre-partition days, is the imperative of control that dominated rugby organisations. The GAA, both as an organisation and a sporting culture, was seen as unruly, savage, and as such opposed to the standardised rules and orderly fashion of rugby, schools which had rugby pitches, and the Empire itself. Similarly, the whole issue around Sunday rugby (yes, playing rugby on Sundays) was not exactly about God’s day of rest as much as about controlling how rugby is played, who plays it, and how money is made through it.

Similar questions can be asked in regard to the transition from amateur rugby organising to the professional system of today. O’Callaghan at one point floats the thesis that Ger Earls could not show his full potential in the amateur setting of 20th century Irish rugby, while his son thrives in the professional setting where “merit alone [matters]”. O’Callaghan’s understanding of issues around amateur rugby is nuanced and it recognises how it was tightly coupled with class issues in rugby. He also undertakes a very good analysis of why and how professional rugby became the only way forward for the sport. I read this part of the book with a particular interest, influenced by my parallel readingof The Lost Gaels: the importance of amateurism in GAA is explicit. Of course, context is crucial, and among many contributing factors, the international rugby scene has had a big impact on the development of Irish rugby.

This international angle is well covered in O’Callaghan’s writing, through the lens of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement mobilising the public against the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) maintaining links, playing games against, and going for tours in apartheid South Africa. O’Callaghan notes how the anti-apartheid sports boycott calls come in the times of war in the North of Ireland, and how the rugby union navigated the landscape of conflict, as well as the positions of authorities on both sides of the British-imposed border.

Both Lost Gaels, written by Peadar Thompson and published by Merrion Press in 2024, and Blood and Thunder, written by Liam O’Callaghan and published by Sandycove/Penguin in 2024 are available from Connolly Books, Temple Bar, Dublin.