East German Literature: Challenges and Triumphs in Cultural Recognition

Germany’s minister of state for culture, the senior Green politician Claudia Roth, one of the almost exclusively West German-born government officials, voiced her surprise at a recent literary event upon discovering that there were other books on East German (GDR) bookshelves than the ones she knew. This was a rare admission of sheer ignorance of the cultural background of one fifth of the German population – well over thirty years after ‘unification’.

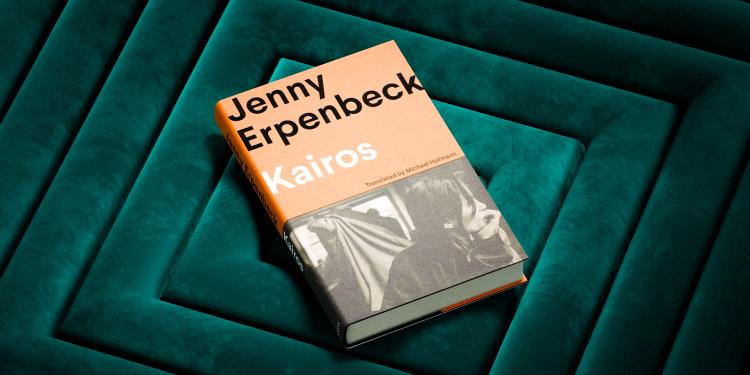

And so it is all the more wonderful that the East German author Jenny Erpenbeck has just won the International Booker Prize 2024 for her novel Kairos. No other German author has achieved this. Literary prizes are awarded to writers who reinforce the Western hegemony of ideas. Any attempt to grapple with the radical denial of achievements and well-lived lives is suppressed or ridiculed. While Jenny Erpenbeck is well-known abroad, she has never won the German Book Prize or the Leipzig Book Fair Prize.

To read Erpenbeck’s novel is an eye-opener for those who wish to find out more about life in East Germany (GDR) in the final years of its existence and beyond. Unprejudiced readers will discover a highly cultured society, a place where everybody has free access to education, training and a job. For readers who remember the GDR, the book includes deeper levels of meaning – a wealth of references to a dizzying array of fine artists who lived there or those who were part of the antifascist tradition.

The novel spans the years 1986 to 1992, with the final section depicting the dissolution of the state, mass redundancies, plunges into unemployment, unaffordable rents and cultural hollowness. Erpenbeck knows what she is writing about: She was a young adult during the years the novel is set. Her paternal grandparents had been persecuted in Nazi Germany and lived in exile in the USSR, where her father was born. Both her grandparents were well-known authors in the GDR – her grandfather, Fritz Erpenbeck, was a publisher and wrote crime novels, and her grandmother Hedda Zinna addressed many themes, including the situation of women in the GDR. Erpenbeck’s father, John Erpenbeck, is a physicist and a writer. Her mother was an Arabist who lost her academic post with unification.

Jenny Erpenbeck builds her story of the final years of the GDR around the narrative of a relationship between a 19-year-old woman, Katharina, and a 53-year-old writer and radio broadcaster, Hans. The relationship soon develops into one of psychological control and masochistic overtones, making the young woman feel unworthy and dependent. Erpenbeck portrays her male protagonist Hans as a very well-read author who has had frequent affairs. In several respects, his childhood in Nazi Germany has cast shadows on his adulthood. This includes Hans’ need to blame and punish others for perceived ‘betrayal’, his latent violence, his need to feel superior and be controlling.

Katharina, on the other hand, only realizes late on that the relationship is destroying her, because she considers herself emancipated. Hans’ trajectory from a Hitler Youth to one who now unquestioningly follows a different flag is representative for his generation, while Katharina is more characteristic of her own age group, born into the GDR and naive to Hans’ manipulation.

Why does the author connect the story of this affair with the collapse of socialism? Erpenbeck herself explains in an interview that “Betrayal and lying are at the center of my work, as are the layers of truth”. When Hans in a fit of jealousy emotionally torments Katharina for having a fling with someone her own age while on work practice, she learns that if “I tell the truth, I get punished.” However, she adds, “we are coming to a similar time now, because there are certain sentences that you are supposed to deliver and others sentences that you are not supposed to deliver anymore.” Erpenbeck does not turn a blind eye to the new reality of post-socialist Germany.

Aside from the relationship at the heart of the novel, Erpenbeck strives to capture not the spectacular or dramatic, but the everyday lives of people. Hans’ knowledge of early post-war cold-war history certainly adds to the deeper dimensions of history, reflecting times before Katharina was born. This includes, for example, the efforts made by the Soviet Union for a unified neutral Germany after the war.

As the story progresses to the dissolution of the GDR and its annexation by West Germany, Erpenbeck incorporates detailed references and documents regarding the aspirations of many for socialism. However, the swift emergence of capitalist, semi-colonialist reality soon dashes any hopes for a more democratic socialist system.

In contrast to the flood of so-called memoirs of the East, often written by people who have no knowledge or memory of this epoch, Erpenbeck’s narrative diverges from the prevalent Western discourse. Through her portrayal of ordinary lives, she poignantly illustrates the losses endured after 1990. There are no signs of dissatisfaction or social unhappiness on the part of the characters and their wider circles. In the book’s concluding section, the atmosphere during the fall of the Berlin Wall is vividly recreated.

Erpenbeck provides an insider’s perspective. Her characters are believable and lead fulfilling lives. East German readers appreciate Erpenbeck’s portrayal of their lives and achievements, which resonates with their own experiences and preserves their dignity.